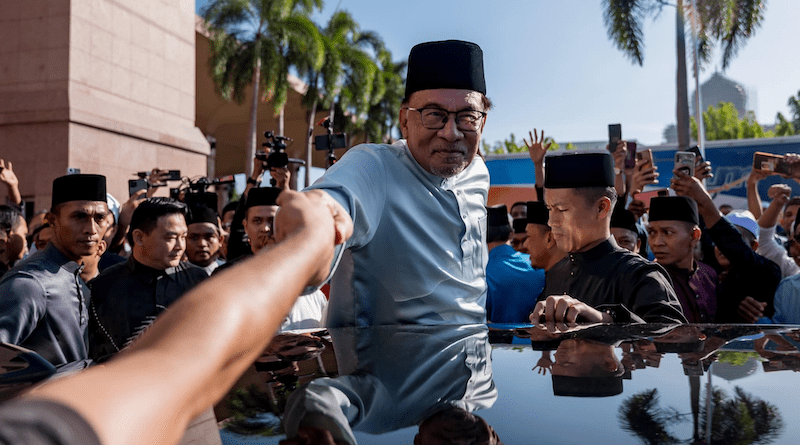

Can Anwar Government Hang On In Malaysia? – Analysis

By BenarNews

By Zachary Abuza

Malaysia’s Pakatan Harapan government has always been precarious. And it may face a reckoning when six Malay-majority states go to the polls on Aug. 12.

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s Pakatan will be contesting these state assembly elections alongside its federal government partner, UMNO.

They face a formidable opposition in Muhyiddin Yassin’s Perikatan Nasional, which projects itself as the standard bearer for Malay Muslims – a voter base long faithful in the past to the United Malays National Organization.

After the general election last November, the two coalitions vied to form a government. For days, it was almost a hung parliament.

Pakatan won 82 seats, while Perikatan won 74 seats.

For Perikatan, its coalition member, the hardline Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS), was the single largest recipient of votes with 49 seats. Perikatan captured an estimated 60% of all Malay voters.

Both coalitions sought the support of other key Malay parties. They were the largely discredited UMNO, which won a mere 26 seats, and the two coalitions from eastern Malaysia – Gabungan Parti Sarawak (GPS), with 23 seats, and Gabungan Rakyat Sabah (GRS), with six seats.

After significant horse trading, Anwar emerged victorious, putting together a coalition of coalitions with 148 of 222 seats, and was named prime minister. He agreed to join forces with UMNO, the very party his coalition had opposed in the 2018 general election, when Pakatan campaigned on a platform of purging the government of deep-seated corruption.

But it was always going to be a fragile alliance, made up of parties who mistrusted one another.

Meanwhile, Perikatan has never given up hopes of pulling off another Sheraton Putsch, as it did in 2020. Back then, it got several Malay parties to defect from Pakatan Harapan, which at the time led the first opposition government in the country’s history.

Muhyiddin’s legal incentive

Could Perikatan do it again? Sadly, yes.

Despite some good news on the economic front, some new foreign investment, the return of tourism, and 5.6% growth in the first quarter of 2023, there’s still room for caution.

Inflation remains fairly high, the cost of living is soaring, and exports are flat. Pledged foreign investment, including $U.S. $39 billion from China, has not yet been committed and may never show up. The weak ringgit may help exporters, but it has made debt servicing and imports costly.

Droughts caused by the El Niño weather pattern, coupled with high temperatures, have hit agriculture hard.

Moreover, the government faces a host of divisive issues.

First, the potential pardon of former Prime Minister Najib Razak who is serving a 12-year sentence for the 1MDB plunder. His acquittal on charges of witness tampering has buoyed his supporters.

Second, Anwar’s government withdrew its appeal of a lower court ruling that allowed non-Muslims to use the word “Allah” for “God.” This has emboldened Perikatan in general, and PAS in particular, to declare that Anwar was unwilling to defend Islam and Malay Muslim interests.

There are a host of other social wedge issues that Perikatan will glom on to, including the rights of religious minorities and the LGBTQ community, especially following the shutdown of a music festival after an on-stage same-sex kiss.

Most of all, Muhyiddin has a legal incentive, not only a political one, to bring down the Anwar government.

On March 9, 2023, the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission arrested the former prime minister for alleged abuse of power by soliciting bribes and money laundering. He was indicted on six counts in total. Muhyiddin has said the arrest was politically motivated, a view widely shared by his coalition supporters.

Polls in mostly Malay-majority states

For both Pakatan and Perikatan, much comes down to next week’s state elections.

Among the six states, Kelantan, Terengganu, and Kedah, are currently controlled by PAS. Perikatan candidates will dominate in all three. In the 2022 general election, Perikatan candidates swept every seat in those three states. Malays comprise 95% of the electorate in the first two, and 76% in Kedah.

The remaining three states are controlled by Pakatan, but two are up for grabs, and will likely turn on the vote of ethnic Malays. The Malay share of the vote in Negeri Sembilan is 56% and 61% in Selangor.

Penang is the safest election for Pakatan, but even there, it can’t take anything for granted. Perikatan made gains in Penang as well in the November polls.

The irony is that Pakatan now depends highly on its coalition partner and historic rival, UMNO, to win back Malays, who make up nearly 70% of the country’s population.

UMNO is contesting 108 of the 245 six states’ assembly seats, but the party is a shadow of its former self.

While it still has its vast political machinery, it has lost much of the Malay vote to its Perikatan rivals as it and its leadership remain tainted by corruption. Its alliance with Pakatan in general, and the ethnic Chinese-dominated Democratic Action Party, in particular, isn’t going to help win back many Malay voters, either.

Anwar’s government at present has 148 of 222 seats, but it’s not as comfortable a margin as one might think – Perikatan only has to peel away 38 seats.

Nearly half of the 26 UMNO members, who were opposed to joining Pakatan in the first place, had already threatened to defect to Muhyiddin’s coalition. Anwar could withstand that loss, but barely.

High national stakes

But if Perikatan does as well as expected in the state polls, it will have national implications. Muhyiddin will claim to have a mandate to form a new government and push for UMNO defections.

And that could open the floodgates: GRS (6 seats) and GPS (23 seats) could be swayed to defect, especially should a majority of UMNO members lead the way – causing the government to collapse.

Anwar is aware of the stakes.

He has campaigned in the states, articulating his economic stewardship, touting foreign investment, and even a big investment from Tesla in Selangor, a project Indonesia had sought to win. He is also likely dangling a cabinet reshuffle, plum assignments, and government contracts, to garner sufficient political support from alliance partners.

Anwar has reminded people of the political instability in the wake of the Sheraton Pustch that badly hurt the economy.

A new Perikatan-led government would likely be every bit as unstable as the governments that came after 2020 and until November 2022, which were marked by incessant political infighting.

A government led by the fundamentalist Islamic PAS would put the country’s minorities and vulnerable populations on edge. And for all those reasons, the economy would be hit hard.

Yet, despite those costs, identity politics remains the driving force, and Pakatan’s multiethnic coalition and agenda is under intense attack as ethnic Malays endorse parties that are committed to advancing the interests of the bumiputera (the sons of the soil).

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington and an adjunct at Georgetown University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Defense, the National War College, Georgetown University or BenarNews.