India Sees Sustainable Growth, China Sinks In Deflation, ASEAN Growth Wobbles: Leaving Japan In A Quandary – OpEd

India heralds new global leadership in geopolitical and economic dynamism. A decade and half ago, the country was in the headlines for poverty, unemployment, red tape and a volatile economy.

In 2014-15, India was the 10th largest economy. Now, it is 5th largest. Average annual growth in GDP was 6.5 percent during 2014-15 to 2022-23. The growth trajectory ascertains India vying for the 3rd largest economy by 2027, proclaimed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

India will be the biggest pool of working population, after China sinks in aging. Given the sustainable growth in the economy, a larger section of people in India crossed above the poverty line. During 2011 to 2019, the share of India’s extreme poverty halved, according to the World Bank.

Agriculture, the base for Indian economy, sparked to nearly 4 percent annual average growth. Inflation (CPI) was contained between 5-6 percent since 2014.

Rural consumption spurred with the expansion of banking facilities to financially weaker and low income people. Currently 78 percent of the population have gotten banking facilities. Banking facilities have enabled for prudent savings.

Export, which has never been the base for growth for India, spurred during COVID 19 pandemic. It peaked at a growth of 45.13 percent in 2021-22 and continued to surge in 2022-23. This translates into a new vitality for India in the global market and a challenge to ASEAN small nations.

In contrast, the Chinese economy was dragged into progressive decline in growth. It is feared to perch on deflation, and its GDP growth fell to 3 percent in 2022 and is projected to fall further in 2023. It faces serious domestic challenges, including an aging population, a rural-urban divide and underdeveloped financial system, according to the IMF.

The deterioration in political relation with the USA and the west dashed China’s export hopes. Till now, “hot politics, cool economics” worked as resilient to economic ties and accelerated China a major trading partner. Low cost production led China to become the biggest workshop for USA, the west and Japan. But, the US-China face-off, Ukraine war and cohesion of China- Russia, has resulted in more barriers to Chinese exports with sanctions and security concerns. Added to this, a mistaken COVID 19 policy hamstrung Chinese growth and traumatized export based industries, by restricting investment.

An aging population emerges as a grave concern for a shortage of working population in China, leading to a rise in the cost of production and vulnerability for the supply chain. The Chinese working age population was 880 million in 2020 and is projected to shrink to 820 million in 2035. Futurists are concerned by the projection that its elderly population will surpass the working population by 2080. Its fertility rate (birth per woman) declined from 2.6 in 1980’s, to 1.15 in 2021.

To this end, China faces multiple challenges and structural imbalances. A shortage in the working population, a slump in productivity, restrictions in transfer of technology due to sanctions, a real estate bubble and elevated unemployment among young workers have all contributed to muting the Chinese growth. Even the leadership appears to have slipped, shaking the aspiration for a strong Chinese Government.

Eventually, the households in China could slip in uncertainty. This will lead them into spending less and placing more deposits in banks, which will decrease domestic demand, akin to Japan’s recession.

Does Japan feel the pinch on China dependency? Japan-China political relations have been on historic roller coaster ties. Notwithstanding, the two nations have been thriving for economic growth depending on each other, following the “hot politics, cool economics” policy.

In 2022, China accounted for around 20 percent of Japan’s total trade. Nearly one fifth of Japan’s imports comes from China, reflecting overdependence for its manufacturing growth.

The biggest product group imported from China is machinery. Nearly, 41 percent imports from China was capital goods in 2019, according to WTIS. Most of these imports include components and parts, according to a report by Mr Kazunobu Hayakawa of JTERO-IDE. In other words, China was indispensable for supply chain to sustain strong manufacturing base in Japan.

Toting Abenomics legacy to dwarf the “China risk”, Japan rewarded manufacturers for de-coupling from China and diversify to ASEAN and hometown in Japan.

Eventually, there was a gradual shift to ASEAN, according to the study by Mr Kazunobu Hayakawa. In 2022, Japan’s total imports from ASEAN increased by 18.6 percent (14.2 percent in 2021), as compared to merely 2 percent increase from China (13.6 percent in 2021) .

De-coupling reflected a reversal for Japanese investment in China. In 2022, it fell by 25.2 percent, against an increase by 10.9 percent in 2021.

Even though ASEAN was pronounced a better alternative to China, Japanese investors were averse to shift wholeheartedly. In 2022, Japanese investment fell in most of the major nations of ASEAN. It plunged in Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia.

No doubt, ASEAN has bounced back in the growth. But, it is yet to be resilient. According to OECD, its GDP grew by 5.6 percent in 2022. But it is likely to decelerate to 4.6 percent in 2023.

Against these paradoxes, even though India witnessed a fall in Japanese investment in 2022, it was moderate (13.4 percent). Given the strong economic parameters, India is ensured for a sustainable growth, unlike ASEAN. The annual average growth in India is expected to be 6.5 percent.

JBIC applauded India’s shining growth. It reiterated India the most promising destination for Japanese business consecutively for 2 years, viz 2021 and 2022, beating out China and USA in its annual survey.

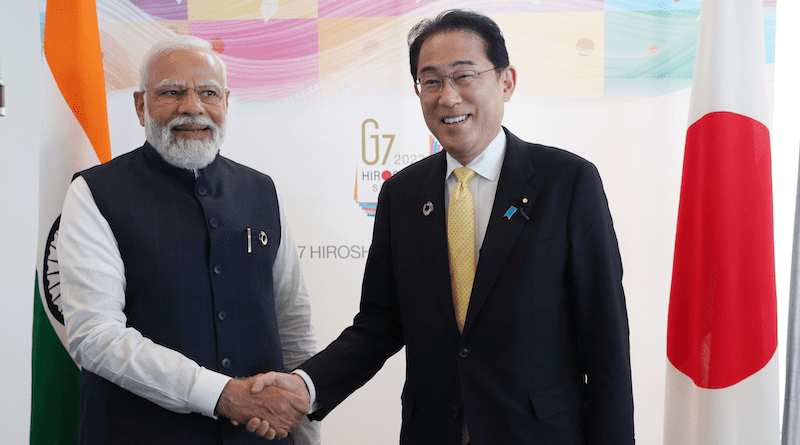

Against these backdrops, should Japan give a new look to India at the upcoming G-20 summit?