Salafism And The ‘Radical Turn’ In Contemporary Islam – Analysis

By K.M. Seethi

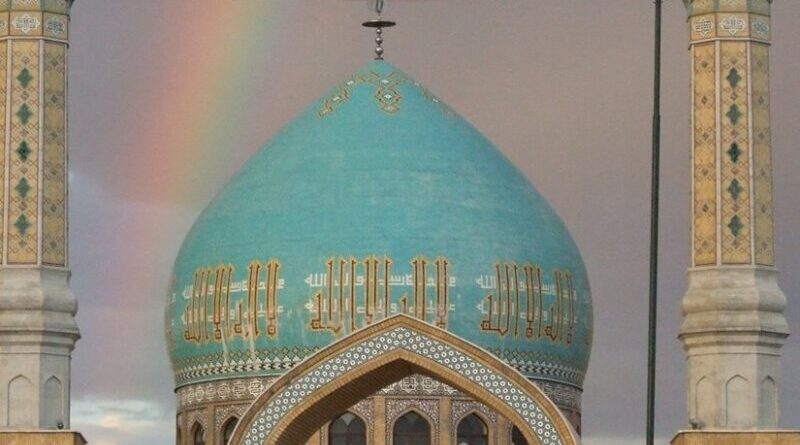

In the aftermath of the devastating bombings at the memorial service for Iranian General Qassem Soleimani in Kerman, where the Islamic State (IS) claimed responsibility for the tragic death of 84 lives and injuries to hundreds of others, concerns about the resurgence of ‘Salafi-Jihadi’ radicalism are once again on the rise. This unsettling turn of events has profound implications for followers of traditional ‘Salafi’ beliefs worldwide, who have historically rejected violence in the name of Islam.

In its conventional sense, ‘Salafism’ refers to a tradition of scholars advocating for Puritan Islam and a liberal-modern interpretation of holy texts like the Quran and Sunnah. However, the original principles of early Salafism face challenges as various groups and organizations in the Muslim world claim to inherit this ideology while disregarding its inherent moral values. The landscape shifted significantly with events such as the 9/11 attacks and unfolding trends in the Islamic world, including the ‘Arab Spring.’ Consequently, the global reformist tradition of Islam finds itself grappling with unprecedented challenges, as these developments introduce new complexities and uncertainties.

The apprehensions surrounding scholars associated with these traditions are unfolding across numerous countries, and even within Islam, ‘reformist’ organizations often face unwarranted branding. A unique encounter from a few years ago in Cairo comes to mind. During my participation in the 4th Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA) and Egyptian Council for Foreign Affairs (ECFA) dialogue, where I spoke on the historical legacy of India-Egyptian relations, I sought to highlight that ideas have historically traversed borders with remarkable speed. In the course of my presentation, I briefly touched upon the profound influence of Egyptian reformists like Muhammed Abduh (1849-1905) and Rashid Rida (1865-1935) on Muslim reformists such as Vakkom Abdul Khader Moulavi (1873-1932) in Kerala during the early twentieth century.

My argument focused on the transformative role played by intellectuals like Abduh and Rida in ushering modernity into Islam. However, a sudden silence fell upon the dialogue platform, and both current and former Egyptian diplomats seemed notably disinterested in the discourse. It became clear that this indifference was rooted in the political implications of my statement. The diplomats, operating within the framework of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s administration, appeared constrained by the political landscape marked by the removal of democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood (MB) leader Mohamed Morsi by then Egyptian army chief General el-Sisi in 2013. This political backdrop rendered any positive discourse related to the MB a sensitive and restrained subject.

How did Abduh and Rida become pariahs in Egypt under the el-Sisi regime? They faced marginalization in Egypt under the el-Sisi regime for a clear-cut reason. Many, both within the Islamic world and beyond, perceived them as ‘Salafis,’ their intellectual legacy seemingly tied to movements like the MB. The MB’s call for a return to the pure roots of Islam was often construed as a precursor to fundamentalism, Islamic revival, and pan-Islamism. This perception drew parallels with the views held towards Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703-1792), the founder of the Wahhabi movement in Arabia, known for its iconoclastic nature. Though ‘Salafism’ and ‘Wahhabism’ were sometimes used interchangeably, differences existed concerning various aspects of Islamic laws and practices.

Over the years, scholars and movements consistently associated Salafi and Wahhabi ideologies with fundamentalism and Jihadi violence, often overlooking the diversity and contradictions within these intellectual trends. Notably, Abduh himself acknowledged that followers of the Wahhabi movement might denounce many innovations and corruptions in Islam, yet they advocated for a strict interpretation of the literal texts of Islam, disregarding the foundational principles of Islam and the Prophet’s teachings. At the core of ‘Salafiyya’ was the imperative for Islamic renewal or reform, aiming to modernize and update religious law (Sharia), even if it meant embracing Western liberal influence. Whether explicitly or implicitly, Salafis championed the separation of religion and politics, setting themselves apart from contemporary Islamic movements that advocated for their fusion, as seen in political Islam.

Engaging ‘Salafism’ amid the Radicalization of Islam

The concept of Salafism has stirred debates in both Muslim circles and among Western Islamicists and social scientists. Western perspectives on Salafism, largely shaped by media narratives, security studies experts, and policy analysts, tend to emphasize its political aspects while overlooking its intellectual, theological, legal, and cultural dimensions within the broader context of Islamic history. Rooted in Sunni Islam, Salafism emerged in the 19th century during colonial rule in Muslim lands, aiming to address perceived societal decline by advocating a return to the pristine age of Islam. Despite misconceptions associating Salafism with a rejection of Western influence and a literal interpretation of religious texts, figures like Muhammed Abduh and Rashid Rida in Egypt offered a liberal and modern interpretation of Islam.

Critics argue that Salafism, originating from theologians like Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328), encompasses both purist and militant factions. Early Salafism displayed a more flexible interpretation of sacred texts, but contemporary militant-jihadi segments like IS, Al-Qaida, and Taliban emphasize a literal and traditional reading. They reject later interpretations, seeking to restore Islamic doctrines to their pure form and focusing on eliminating idolatry. Despite contemporary divisions into different categories, the ultimate goal of Salafism is not political power but the education and cultivation of Muslims in Islamic monotheism and adherence to the Sunnah of the Prophet.

In the evolving landscape of political movements in recent decades, various forms of religious activism, from Islamism to Islamic nationalism and neo-fundamentalism, have emerged with distinct objectives, values, and ideologies. Salafism is perceived as divergent from moderate Islamism’s vision of a democratic state, as militant Salafists advocate enforced social uniformity and urge Muslims to separate from Western societies. The establishment of the caliphate is considered a long-term goal by some, such as IS and MB. Despite not constituting a majority in the Middle East and North Africa, Salafis have influenced political agendas through significant funding from wealthy Gulf monarchies.

Wahhabism, a parallel reformist movement to Salafism, emerged in the eighteenth century, emphasizing moral reconstruction through a return to monotheism. Wahhabism opposed Western influence and the intellectual, artistic, and mystical traditions of Islam. Originating in the eighteenth century, it gained prominence through its partnership with Muhammad Ibn Saud, leading to the unification of tribes in the Arabian Peninsula. The alliance endured, forming the basis of the modern Saudi state in 1932, with Wahhabism’s influence surging with the discovery of oil. The consequences of its global promotion include the rise of a militant and radicalized form known as ‘neo-Wahhabism,’ contributing to the emergence of Salafist jihadism.

In recent years, Salafism has gained global influence as an alternative to perceived failures of the Muslim Brotherhood’s political model, fuelled by Gulf oil money. While most Salafists are nonviolent, the ideology is susceptible to radicalization, and certain doctrines can be exploited to justify extremism, as seen in groups like DAESH (IS) and Al-Qaeda. Despite this, the appeal of today’s Salafism lies in its emphasis on authenticity and legitimacy, drawing interest among Muslims with varied interpretations and applications.

Contemporary Salafism encompasses a religious inclination towards a set of ideas and identity, advocating strict adherence to the practices of Prophet Muhammad and the early Muslim generations known as the Salaf al-Salih. The ideology, rooted in the teachings of the Quran and Sunnah, attracts the younger generation by asserting legitimacy and authenticity, offering simplistic solutions to contemporary dilemmas, and positioning itself as an active force in the political, social, and economic spheres.

In the context of Muslims living as minority communities globally, Salafism poses challenges due to its distinct and exclusive teachings. While its appeal is multifaceted, the implications of radical Salafism can be profound in today’s socio-political reality, with potential consequences for Muslims in non-Islamic or secular systems.

Thus, the jihadi narrative promoted by groups like Al-Qaeda, Taliban, and IS poses a significant threat, capable of disrupting both political structures and societies. Regrettably, this ‘radical turn’ has cast a shadow even over modern, liberal, and reformist traditions of Islam. These traditions face branding and portrayals by conservative ulama from both Sunni and Shia Islam, adding an unfortunate dimension to the challenges posed by radical ideologies.