Why Political Parties Do Not Work In Philippine Elections? – Analysis

Introduction

In a month’s time this year, Philippine national elections will be concluded with a new set of leaders, particularly the President and Vice-President. Whether or not these new leaders won as a result of more powerful and better platform of government or advocated national policies by their political party compared to other contending political parties, among others, is determined by the nature and character of the country’s political party system.

The presence of diverse political parties in the country under a presidential system does not necessarily mean that electorates are offered with an array of varied political programs to choose from, as there are few, if any. As elections are held every three (3) years in the Philippines, it is important to understand how political parties figure out in carrying politicians to victory or trouncing. This piece examines briefly political parties in the Philippines and how they perform their role in the country’s electoral politics.

Birth and evolution of Philippine electoral system

Philippine electoral politics has deep historical roots, commencing under the auspices of American colonial rule with the conduct of the first direct local elections in 1906 and the first national legislative election (Philippine Assembly) in 1907. On these occasions, the electoral system in Philippine politics has been introduced. The Americans brought in the right of popular suffrage to the country. The imposition of the system of voting in a predominantly feudal and agrarian society where patron-client relationship pervades, i.e., defined as a mutual arrangement between a person who has authority, social status, wealth, or some other personal resource (patron/landlord) and another who benefits from the former’s resources (client/farmer or tenant), effectively configures the relationship between the politician and voter (see Landé, 1966 for details).

Originating as a social custom, patron-client relationship became entrenched in politics as well as in elections. Well-organized landlords traditionally got themselves elected to legislative and executive bodies of government. The peasants on their lands had no ability to organize and assert their interests. They voted as their landlords told them to do.

Thus, in spite of the trappings of civil and political institutions introduced by the colonizers, Filipino values and characteristics of familialism, personalism, and parochialism persisted and failed to develop among the people the concept of social well-being or national welfare (Abueva 1971, pp. 1-24). The feudal patron-client relationship persists, survives, and continues at the 21st century’s elections with some few insignificant changes, unfortunately.

Political party system

The main characteristic of the Philippine political party system since Philippine independence in 1946 has been the two-party system. Two major parties, the Nacionalista and the Liberal, dominate the scene. While a third party, the Progressive Party, participated in the 1957 presidential election, it was not able to seriously threaten to replace either of the two existing major parties as the governing party or as the principal party of the opposition. Interchangeably, Nacionalista and Liberal parties governed the country without much difference in programs, ideologies, and policies.

The years after independence and prior to the declaration of martial rule in 1972, i.e., 1946 to 1969, presidents have been members of one political party and shift to another party or founded a new one to run for president. For instance, Manuel Roxas, then a senator under the Nacionalista party (NP) absconded NP and founded the Liberal party (LP) to run against Sergio Osmena who after Roxas was defeated him in the Nacionalista nominating convention for the presidency; Elpidio Quirino who was elected as a member of the House of the Representative (HoR) under the NP joined the LP, run for vice-president and subsequently succeeded Roxas when he died, and eventually won the presidency in the 1949 presidential election; Ramon Magsaysay, a member of LP switched to NP to challenge Quirino to the presidency; Ferdinand Marcos, an LP member likewise change his colour to NP and run against his former partymate Diosdado Macapagal in 1965, and was re-elected in 1969 election.

Evidently, absence of any discernible ideological or philosophical differences between political parties made party-switching or “turncoatism” a common feature of Philippine politics, both national and local. What is important to the life of Philippine political parties is the accession or defection of village leaders, mayors, governors, congressmen, and senators toward the party with the spoils.

After elections, politicians feel no obligation to their party. Loyalty shifts are lamely justified by the usual political cliché, “requirement of our constituents” or “dictates of patriotism” (Villacorta 1990, p. 45). Political principles and party affiliation take the back seat. Selection of political leaders in the country revolves around personalities rather than issues.

In 1972 when martial law was declared and an authoritarian government was established, several politicians ditched their respective party affiliations and joined the monolithic party of Marcos – the KBL (Kilusang Bagong Lipunan orNew Society Movement). Former oppositionists began to jockey forrecognition and positions in the KBL leadership, bringing about disunity in the opposition party. And in 1986 when President Aquino assumed presidency through extra-constitutional means, a massive exodus of known KBL politicians who defended Marcos even in his last few days in power were able to successfully slip into the coalition party of Aquino under the wings of “reconciliation and re-democratization.”

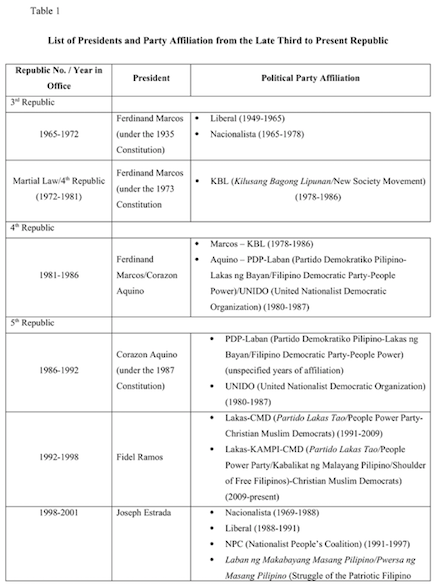

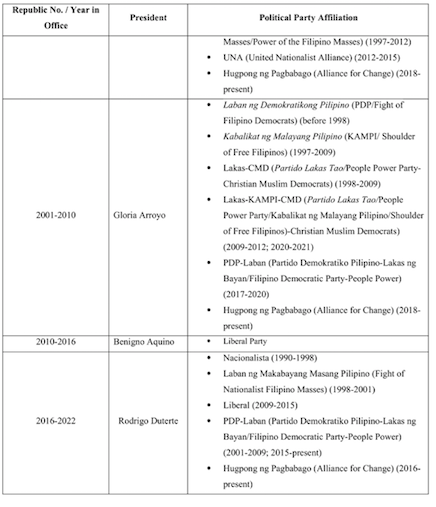

The abandonment of the two-party system and adoption of an open and multi-party system under the duly endorsed 1987 Constitution further institutionalized and facilitated political turncoatism. The table 1 below succinctly displays the Presidents the country had/has (including the current one as of this writing) from the third to fifth Republic who had been affiliated with assorted political parties (sometimes associated with different political parties simultaneously) with no distinguishing features like strategic vision nor clear and comprehensive program of government; not even distinctive ideology, philosophy, standpoint, and viewpoint. Note that only President Benigno Aquino (2010-2016) remained with a single party (LP).

For more than half-a-century, these attributes of Philippine party system have survived and yet neither institutional nor structural changes have fundamentally altered. While the alteration of parties in power corroborated the operation of “democracy,” it also heralded the deep popular dissatisfaction of people with every presidency. Croissant and Lorenz (2018) characterize Philippine party system as highly ‘defective elite democracy.’ The elite effectively remains in control over the country’s political processes and outcomes.

Philippine electoral party system hitherto is largely a one-party/multi-faction system in spite of the proliferation of political parties. Electoral candidates’ commonalities lie in their class bases, elite origins, and interests they represent. Hicken (2018) attributes the oligarchic control of political parties and paucity of politically active citizenry or mass organizations to the ‘under institutionalized’ Philippine political party system. He contends that an under-institutionalized political party hinders democratic consolidation and good governance as it undermines the ability of voters to hold politicians accountable and produces ambivalence among voters on the merits of a democratic society.

More of the same

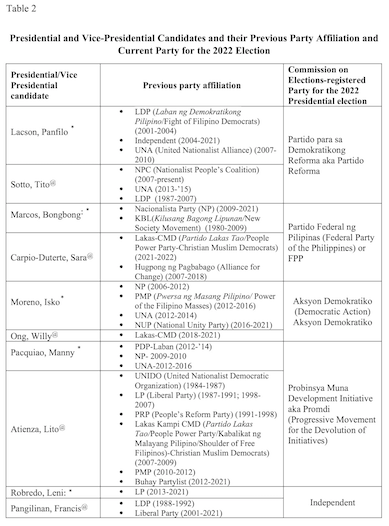

In the forthcoming 2022 national and local elections, just like 76 years ago, political parties will remain a collection of non-sensical groupings — unable to distinguish themselves from each other and allow the electorates differentiate themselves in terms of policies, ideologies, or government’s program variations from each other. The facility of candidates and politicians to swing from one party to another illustrate that electoral parties are plainly factions of a single class – the elite. Parties do not mean anything to both candidates/politicians and voters. For brevity, table 2 exhibits the array of political parties that main presidential and vice-presidential candidates have been previously affiliated and the current political party they are associated with in the upcoming elections.

Conclusion

For more than seven (7) decades, Philippine party system has yet to achieve its purpose in a democratic society. Having branded to have experienced a two-party system (1946-1972), single-party system (martial law period, 1972-1986), and multi-party (1987 to present), electoral parties are no different from each other. If ever parties have clear platform of government, philosophy, ideology, or strategic policy, they are neither distinguishable nor discernable from each other. Given the political similarities of parties, it is no reason for candidates to shift from one party to another nor any moral obligation not to.

Apart from non-distinguishability of political platforms, the class composition of party candidates is no different. They are generally dominated by the elite, oligarchs, and the privileged class. While people are free to exercise their right of suffrage, their choice of political leaders are limited to the wealthy. In 2021, Panganiban estimates that a candidate for president in the Philippines need to spend P50 billion (est USD975M) to run a decent election campaign. As before, political power in the Philippines has always been concentrated on the hands of the wealthy millionaires and billionaires.

The feeble party system, turncoatism, patronage politics, and elitism have emasculated the processes and institutions of democracy. Any endeavour to reform Philippine party system has to be done in conjunction with the structural changes of the country’s social, economic, and political iniquities. Unless this is resolved, democratizing political parties will simply serve the limited interest of the élite and powerful over the greater interest of the people and nation.

*Rizal G. Buendia, Independent political analyst in Southeast Asian governance based in England and Wales, UK. Philippine Country Expert of the Global V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Former Teaching Fellow at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, UK and former Associate Professor and Chair, Political Science Department, De La Salle University-Manila, Philippines.

References

Abueva, J. (1971). Ramon Magsaysay: a political biography. Manila: Solidaridad Publishing House.

Croissant, A., & Lorenz, P. (2018). Philippines: People power and defective elite democracy. Comparative Politics of Southeast Asia: An Introduction To Governments And Political Regimes (pp. 213–254). Springer.

Hicken, A. (2018). The political party system. In M. R. Thompson, & E. V. C. Batalla (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of the Contemporary Philippines (pp. 38–54). Routledge.

Lande, C. (1966). Leaders, Factions, And Parties: The Structure of Philippine Politics. Southeast Asian Studies, Yale University.

Villacorta, W. (1990). Political contestation in the Philippines: Rhetorics and reality. In N. Mahmood & Z. H. Ahmad (Eds.), Political Contestation: Case Studies From Asia. (pp. 43–54). Sheinemann Asia-Octopus Publishing Asia Pte. Ltd.