The Fact You Can Vote Doesn’t Make Government Abuse OK – OpEd

By MISES

By Ryan McMaken*

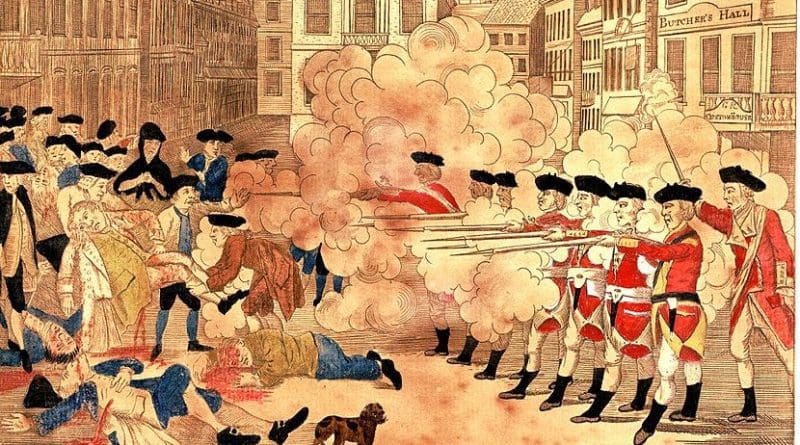

One of the most problematic aspects of the American Revolution — problematic for the state — is the fact that the American war for independence was illegal. According to British law, the secession movement announced at Philadelphia in 1776, and the war fought to defend it, were criminal acts instigated by criminals.

Moreover, the formal act of secession from the British empire, was just one act in what was becoming a well-established habit of resistance to, and disregard for, British law. By the time of the revolution, smuggling and tax evasion in general had become integral parts of the colonial economy and mindset.

Disregarding British Law: A Favorite Pastime of Americans

This went back at least to 1733 when the British state imposed the Molasses Act which slapped a tax on molasses imported from French colonies. This was very costly for New Englanders who not only produced a lot of rum, but also drank a lot of it. Resistance to the tax — and to later taxes — became so widespread that John Adams later remarked that “molasses was an essential ingredient in American independence.”

In his introduction to William McClellan’s Smuggling in the American Colonies at the Outbreak of the Revolution, David Taggart Clark writes:

the restrictions on imports from the West Indies were systematically and persistently ignored, producing a condition of smuggling so universal and well-nigh respectable as to raise the question whether the operations of the merchants could properly be designated by that term.

This disregard for the laws persisted as the colonists found themselves as pawns in the political games of British politicians. British lawmakers limited colonial trade for the purposes of gaining advantage for London in geopolitics, or to assist domestic special interest groups.These trade limitations thus extended far beyond just the West Indies where the molasses trade was important.

The end result was, as McClellan concludes:

Moral scruples had no more weight with the colonists in connection with the general import trade than they had in connection with the West Indies trade and we shall see that smuggling existed in the latter whenever the colonists found it to their advantage.

Flouting trade restriction may have been an important part of planting the seeds of the revolution, but the revolutionary spirit ultimately went far beyond just matters of taxes.

As Murray Rothbard has shown, the American Revolution carried on the ideas of the radicals of the English Civil War, and it served as a catalyst for many radical ideas. These included the abolition of slavery (at least in the North) and the end of state-sanctioned churches. It also brought the near-abolition of the hated standing armies, in favor of local militias as envisioned by the radicals of 17th-century England. And, of course, the Declaration of Independence explicitly established the moral right of political separation — i.e., secession — when governments become destructive to the rights of the people.

Needless to say, all of this was contrary to British law. It was abhorrent to the ideas of those who controlled the British state, and who would have likely hanged the American revolutionaries for treason — if they had had the opportunity.

Why Follow the Law Now?

But once we see that the United States was itself formed out of contempt for established — but unjust — laws, this presents a problem for those who seek to preserve the status quo.

Taggart Clark saw this problem in 1912, wondering:

But the study of colonial smuggling must at least raise a deeper, and perhaps a sadder, question, the question whether sensitive regard for the majesty of law still suffers amongst the American people from the injury wrought by the foolish legislative officiousness of an eighteenth-century English Parliament.

In other words: how do we get these Americans to respect the law even though their country was created by lawbreakers? The revolutionaries supported secession, smuggling, tax evasion, and even taking up arms against the established government. This wouldn’t necessarily be a problem for the state and its supporters were it not for the fact that many Americans continue to revere the revolutionaries and the idea of the American Revolution itself.

The challenge therefore, is to create the impression that the struggle of the revolutionaries has no relevance to today’s political system.

This can be done in a variety of ways, but the one I wish to focus on here is the strategy of portraying the American revolutionaries as an irrelevant model because now we have “democracy.”

“Revolution Is Wrong Because We Have Democracy Now”

The argument goes something like this: the American Revolution was justified way back in the old days because they didn’t have democracy. We know this because they opposed “taxation without representation.” Thus, those taxes, like the notorious tax on tea, were wrong. But none of that applies to America today because now we have democracy. All taxes are approved by “the people” through the ballot box. If you don’t like the taxes, you still have to follow the law because democracy proves the laws are the will of the people. Secession, of course, is no longer acceptable because it’s unnecessary. If there are any unjust laws, people can simply vote for better rulers. And then the problem will be solved. Breaking away and forming a new country, of course, is far too radical and un-patriotic.

And so on.

To say that this explanation of democracy is naive in the extreme would be an understatement. This argument fails not only in terms of how democracy actually works, but also ignores the true history of the Revolution.

For instance, “taxation without representation” was hardly the only grievance of the revolutionaries. In fact, in the Declaration’s list of abuses justifying the colonial secession from the British Empire, the statement “imposing Taxes on us without our Consent” is seventeenth on the list. One would think that if this were the primary cause of the rebellion, then it might appear somewhat sooner in the document. Instead, it comes after a long list of complaints about the appointment of judges, excessive military power, and the creation of “swarms” of regulatory bureaucrats, which the king “sent hither … to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.”

Moreover, the Declaration establishes that the proper end of government is to protect “rights” and that once a government becomes “destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it.” The Declaration does not say the people have a right to alter or abolish an abusive government “except in cases where there are regular elections.” For Jefferson, an abusive government is an abusive government. Democracy doesn’t make an abuse a non-abuse.

Nor does the Declaration establish that if the majority votes for something, then it’s okay for the government to do it. If 51 percent of the population votes year after year to impose onerous regulations, high taxes, and officials hostile to the minority, shall we tell the minority “no resistance is permitted, because we have democracy”?

Such a claim would be absurd, and throughout history, democracy can been shown to lead to abuses far greater than any of those inflicted on the colonists by the British Crown.

Thus, the claim that resistance and rebellion have been rendered taboo by democracy is based largely on fantasy and wishful thinking.

And then, of course, there is the problem of political representation itself. As Gerard Casey has shown, the idea that elected “representatives” can faithfully represent the needs and views of the general public is highly suspect at best. To see this, we need look no further than the reality in America today.

For example, most members of Congress are millionaires, and on average, each member of Congress has the wealth of eighteen American households. Members also spend most of their time in Washington, eating steak lunches with lobbyists and living a standard of living of which most Americans could only dream. Members of the Senate are even wealthier and more out of touch.

Each member of the House of Representatives also represents, on average, nearly 600,000 constituents, meaning the vote of each individual constituent is essentially meaningless to the elected official. To get face time with one of these “representatives” usually requires making a large “contribution” to the politician’s re-election campaign. What is the likelihood that your representative will share your worldview, your religion, your ethnic identity, and your economic interests? The probable answer is “zero.”

But for some, this model of political representation renders all political disobedience, secession, and rebellion irrelevant to today’s world. By this way of thinking, who needs rebellion? Your Millionaire-in-Congress will faithfully represent you! Unless, of course, the majority repeatedly elects representatives who are hostile to your way of life.

And finally, we might also note that countless American laws and regulations are made, not by any elected body, but by the vast, faceless unelected bureaucracy that functions out of reach of the voters. Each year, thousands upon thousands of new rules — many of which are enforced with sizable fines and jail time — are imposed on citizens who have no means of making the rule-makers accountable.

The Revolutionary Spirit Is Just as Relevant as Ever

The reality of the revolutionaries of old is far more relevant to our own times than many would like to admit. Millions of Americans are governed by a faraway and unresponsive elite. Taxes in the form of tariffs can be increased — and are being increased — by a president who can impose these new taxes with the stroke of a pen and without any vote in Congress. As in the time of the Revolution, locally-made laws are rendered null and void by distant government officials. Except now we call it “judicial review.”

“But don’t question the lawfulness of the system,” we’re told. Don’t talk about secession, or nullification, or disobedience at all. It’s all “legitimate” now because we have democracy.

Unfortunately, many people believe it.

About the author:

*Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is the editor of Mises Wire and The Austrian. Send him your article submissions, but read article guidelines first. Ryan has degrees in economics and political science from the University of Colorado, and was the economist for the Colorado Division of Housing from 2009 to 2014. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

Source:

This article was published by the MISES Institute