Poll Mired In Controversy Reveals Many Slovaks’ Wish For Russian Victory – Analysis

Despite heated debate over the methodology used in the survey, experts are not shocked by the latest findings.

By Peter Dlhopolec

A recently published survey that showed a significant number of Slovaks want Russia to win the war in Ukraine has sparked huge controversy in the country.

Jakub Goda, a noted disinformation fighter, was among the first people to share his initial scepticism over the survey, published on September 14, and to ponder why it had to be wrong in light of previous research that had told a different story.

In a Facebook post, Goda alluded to data published by the Bratislava-based think-tank Globsec in May. Despite the strong presence of Russian propagandain the country’s media landscape, the data found that more than 50 per cent of Slovaks blamed Russia for the war in Ukraine, 62 per cent of Slovaks perceived Russia as a threat, and 72 per cent supported NATO in late March.

“I just can’t admit it’s even darker than I thought, so I’m speculating and looking for excuses,” Goda wrote on Facebook, as he questioned the 10-point scale used and even the polling agency itself that carried out the survey.

The polling agency in question was MNFORCE, which together with the Slovak Academy of Sciences (SAV) produced the latest “How Are You, Slovakia?” survey. Over the last two years, this survey has sought to map Slovaks’ attitudes shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. The polling agency asked 1,000 respondents 54 questions via the internet on July 18-22, of which two questions concerned Russia’s war against Ukraine.

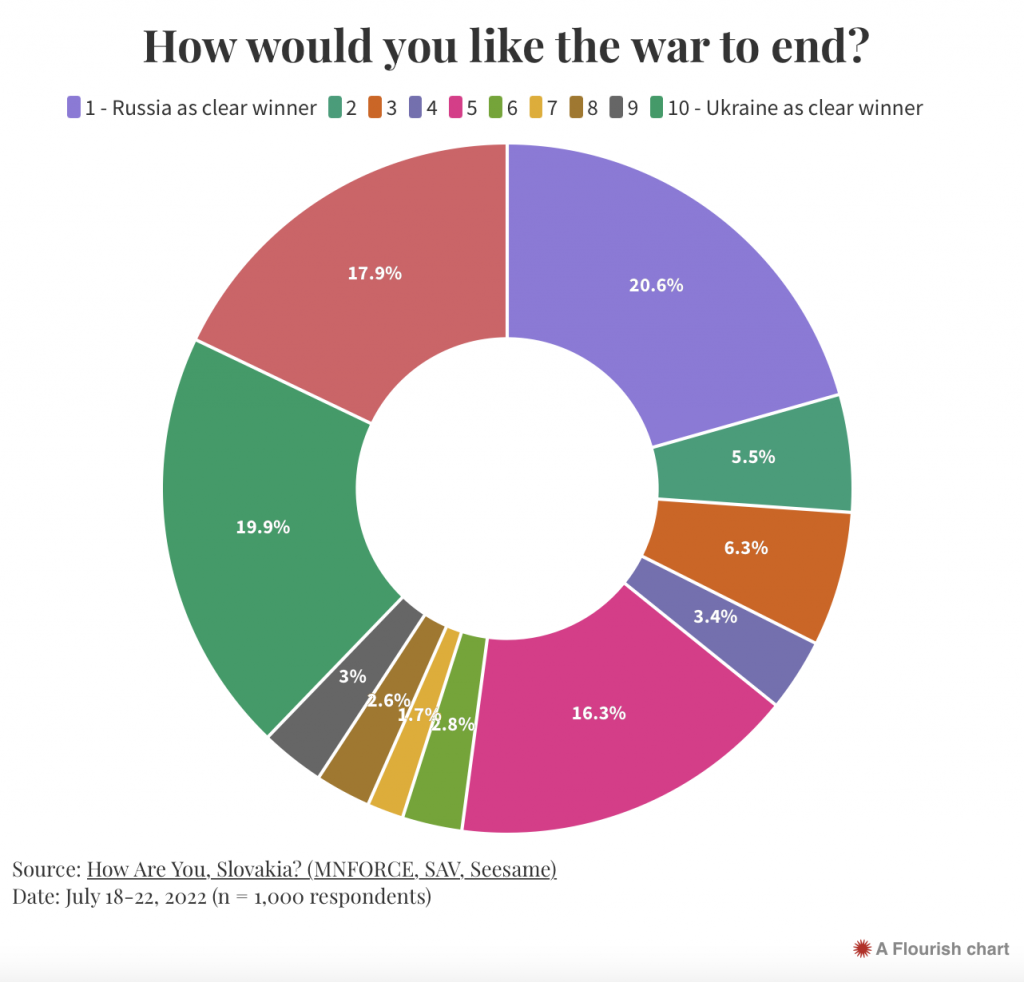

As soon as the Denník N daily on September 14 published its analysis of one of those two questions, “How would you like the war to end?”, the polling numbers caused a huge uproar. As well as heated debate on social media, several foreign news outlets also shared the numbers on their websites.

According to the survey, 20.6 per cent of respondents said in July that they would definitely want Russia to be the clear winner of the war compared to 19.9 per cent of respondents who said the same about Ukraine.

Yet it was the 1-10 rating scale used in the survey, which researchers employed to evaluate to what extent respondents might wish for a victory by Ukraine or Russia in the war, that has divided people the most.

To dismiss any doubts about the survey, whose findings in its entirety will be published in several months, Denník N journalist Daniel Kerekes followed up on his analysis and published an interview with SAV sociologist Miloslav Bahna, one of the survey’s authors.

While Goda has accepted Kerekes’ 13-point Facebook explanation concerning the survey and Bahna’s defence of its results, Ukraine expert and prime ministerial advisor Alexander Duleba took a different line.

“The survey has no informative value,” Duleba told Rádio Expres, the most listened to radio station in the country, in his criticism of the applied methodology.

Yet information security expert Tomáš Kriššák from the Gerulata Technologies firm disagreed and said he considers the survey to be a warning sign. “Information security has been underestimated in Slovakia for a long time,” he said.

Most or many Slovaks?

Experts underline that polling is not an exact science and that surveys paint a picture of a situation at the particular time when they are undertaken.

In the weeks leading up to the survey, Russia was faring better than Ukraine in the conflict even though Ukraine continued to receive weapons from the West. NATO had invited Finland and Sweden to join the alliance and agreed to expand troops at high readiness. And a political crisis in Slovakia and the war-induced energy crisis were beginning to appear more frequently as topics in the media. All these news stories, in addition to Russian propaganda and pro-Russian views held and presented by some high-profile Slovak politicians like former prime minister Robert Fico, could have been shaping respondents’ views one way or another.

Looking at the rating scale and the mathematical results, up to 52.1 per cent of respondents (1-5) said they wish for a Russian victory, while 30 per cent (6-10) said they hope Ukraine will win. Almost 18 per cent said, “I don’t know”.

Among the people who expressed most support for Russia in the survey were those who remain unvaccinated, support far-right parties or the former ruling party Smer, and are less educated.

Surprisingly, respondents in their 30s held the strongest pro-Russian views, according to the published data. It is usually Slovak pensioners who have the highest sympathy for Russia.

Bahna, who stands behind his decision to use the 10-point scale despite the criticism, has said he defines the values from 4 to 7 as the in-between/neutral position. “In the case of the asked question, it would mean a wish for a tie between Russia and Ukraine,” the sociologist said.

Hence, the percentage of respondents wishing for a Russian victory (1-3) would stand at 32.4 per cent. Conversely, 25.5 per cent would represent the respondents (8-10) who would want Ukraine to defeat Russia.

If the 4-7 values and the “I don’t know” percentage were totted up, it would mean that 42.1 per cent wish for a tie or have no interest in the war.

Experts such as Václav Hřích, head of the AKO polling agency, and Dominika Hajdu from Globsec see a problem in the use of the detailed rating scale, they told the Markíza television channel. Hřích said he would have preferred a simpler scale, while Hajdu pointed out that Slovaks tend to mark “5” instead of “I don’t know” in surveys to avoid admitting that they do not know the answer. Yet “5” does not represent a neutral number mathematically, something which people might forget when filling in a survey.

Moreover, before respondents answered the question of who they think should win the war, they had to answer the question on how the war should end. “The opinion that Russia would win significantly prevailed,” Bahna revealed to Denník N.

He also admitted that some respondents could have overlooked the difference in the meaning of the second question. “However, most answers are not identical,” he emphasised.

The sociologist also defended the method employed of online polling even if people without internet access had been excluded from the survey. After two years of applying the methodology and comparing it with others, he said the differences are negligible.

As for the quality of respondents who are rewarded and used by MNFORCE, researchers behind the survey said the polling agency is a member of ESOMAR, an organisation that advocates for the ethical and responsible use of data in analytics and research.

Another criticism raised by some on social media concerned MNFORCE owner Andrej Kičura, who is related to Kajetán Kičura. The latter is a former high-ranking civil servant who is facing charges of corruption and manipulation in public procurement.

“It’s a coincidence,” said Juraj Caránek from Seesame, a PR agency involved in the “How are you, Slovakia?” surveys. Kajetán Kičura has nothing to do with MNFORCE and does not pay for the surveys, he stressed.

Propaganda and national egoism

More than seven months into the war in Ukraine, the conflict has transformed from a reality that scared Slovaks and sparked solidarity with its refugees into a polarising political topic.

Soon after the invasion began, MNFORCE and SAV conducted a quick surveyon whether Slovaks agreed with their government’s condemnation of the invasion: 78.2 per cent supported the decision, though only 42 per cent were fully convinced the decision was right. When respondents were asked about Slovakia’s geopolitical orientation in April, 46 per cent said Slovakia should stay neutral between Russia and the West. Only 8 per cent said Slovakia should take the side of Russia, and the number of those who would rather stand by the West had increased to 39 per cent from 26 per cent in 2014.

Yet the initially encouraging numbers and solidarity seem to be reversing. For example, refugees are now increasingly seen as a burden on Slovak society.

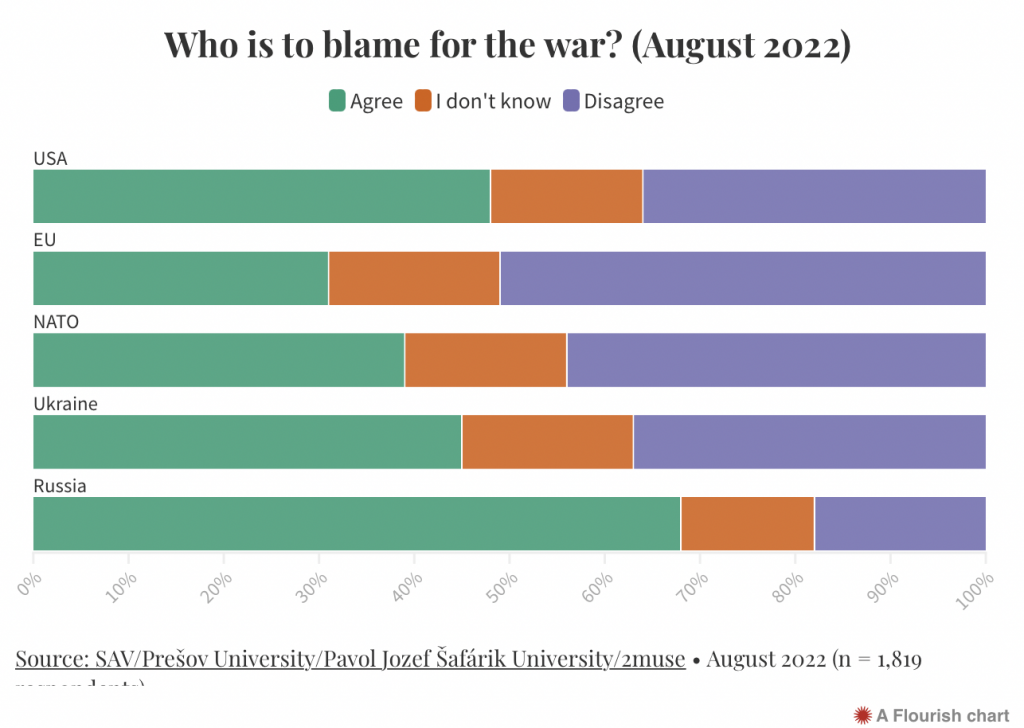

Since the start of the war, researchers have also asked the question “Who is to blame for the war?” In March, 76 per cent of 1,851 respondents blamed Russia. That number had dropped to 68 per cent in August, online polls by SAV and two universities in eastern Slovakia showed.

“Even in this case, it is not clear that the majority of the public would be strongly convinced that only Russia is the aggressor,” Bahna told Denník N.

Kriššák is not surprised by the declining support for Ukraine in such a polarised society as Slovakia’s. The Slovak information space has been under the control of Russian propaganda spreaders for a long time, he noted.

Slovakia is one of the most vulnerable countries to conspiracy theories in the region, according to this year’s Globsec report. Back in May, members of the US Congress wrote a letter to Facebook to do more to fight disinformation on the Slovak-language version of Facebook.

“The control of the narrative also translates into the formation of public opinion and how people think about and frame current events,” Kriššák said.

Other experts share this view. Hajdu from Globsec said she wasn’t particularly shocked by SAV and MNFORCE’s latest findings either. As she told Markíza, about a third of Slovaks seem to be Russophiles no matter what happens.

Political analyst Grigorij Mesežnikov, on the other hand, described the findings as the broken moral compass of Slovaks. “Overlooking what’s happening in Ukraine, caring only about energy prices and pointing to problems that the war brings about for Slovakia is national egoism,” the political analyst said.

The ex-Slovak finance minister and a former advisor to Ukrainian politicians, Ivan Mikloš, went even further in an op-ed for the Sme daily, in which he wrote that Slovaks who wish for a victory to Russia do not really consider Slovakia their home.

“If our home, our homeland and values such as freedom, independence, our territorial integrity are important to us, then we understand their importance and sanctity not only in the event of them being threatened at home, but also everywhere else, even more so in the neighbouring country,” he wrote.