India’s Myanmar Challenge – OpEd

In early November, a coalition of Myanmarese ethnic rebel armies that calls itself The Brotherhood Alliance started a powerful offensive that could mark the turning point in the country’s ongoing civil war. The civil war has intensified after the February 2021 coup which put an end not only to its fledgling democracy but also attempts at ethnic reconciliation through a comprehensive nationwide ceasefire and dialogue.

The Brotherhood Alliance , a tripartite military alliance comprising the Arakan Army, Ta’an National Liberation Army and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, launched simultaneous attacks and within a week had captured strategic towns in the northern Shan and Mandalay regions that helped them take control of all the key trade routes between Myanmar and China, including the busiest border checkpoint in Muse and Chin Shwe Haw, a trading town that borders China. A nervous Beijing called for an immediate ceasefire, a call that the insurgents have not heeded so far.

The offensive has caught the Burmese military junta off guard, as its intelligence apparatus failed to warn the military command in Naypyitaw with advance intelligence on the launch of the attacks.

The Brotherhood Alliance’s control over areas like Kutkai, Muse, Lashio, Namkham, Nawnghkio and Chin Shwe Haw in the northern Shan state and the ruby mining area of Mogoke in the upper Mandalay region will help the rebels cornes huge revenues that will bolster not only their strategic dominance but also firepower. The rebel operation 1027 has also blocked lucrative trade routes between China and Myanmar – the Lashio-Muse Highway and Lashio-Chin Shwe Haw Road – to prevent regime reinforcements from using them. All trade routes with China, including the busiest border checkpoint in Muse, are now reportedly under Brotherhood Alliance control and currently closed due to ongoing fighting. Chin Shwe Haw, a trading town that borders China, also fell to the insurgents.

Myanmar shares a 2,129-kilometre long border with China. In the last three and a half decades, Myanmar has developed a particularly strong business relation with China. According to Myanmar’s Ministry of Commerce, the bilateral trade between the two countries from April 2022 to the middle of January 2023 had touched $159.412 million, much of which is conducted overland through the well-managed border checkposts. Though the military junta supremo Senior General Min Aung Hlaing has vowed to seize back all terrorities lost, analysts say it is easier said than done because the foot soldiers of Tatmadaw, often without timely pay and leave, are a demoralised lot especially while operating in outlying areas. High rates of desertion from the rank and file and even mutinies against officers have often been reported from conflict zones.

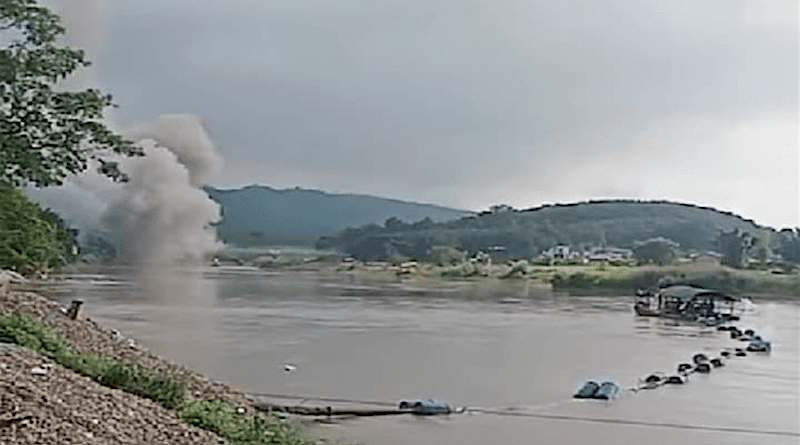

There are also indications that the Arakan Army down south, that already controls key trade routes to Bangladesh, are preparing for a final push after having gained effective control over two-thirds of the key coastal province of Rakhine and large parts of the neighbouring Chin state. Their alliance with the Rohingya Muslim rebel groups, clearly designed to gain global support from the Islamic world, has also made public opinion in Bangladesh more receptive to helping them. The only card up the military junta’s sleeves is Myanmar’s combat airpower that is likely to be bolstered by purchase of Sukhoi fighter-bombers and helicopter gunships from Russia, but with reports that the US is covertly supplying both shoulder fired anti-aircraft missiles (that provided deadly in Ukraine) and armed drones to the rebel groups, Min Aung Hlaing’s hour of reckoning is not far off.

Despite the junta’s close – almost surrogate – relations with China, Gen Hlaing’s close associates remain wary about Chinese intent on a host of issues – be it weaponising ethnic groups like the United Wa State Army (which monopolises the synthetic drug trade in the ‘Golden Triangle), debt scares, or, unsustainable projects like the multi-billion Kyaukphyu deep sea port in Rakhine coast or the 6000 MW Myitsone hydel project (which has not moved ahead since work on its was stalled in 2010).

If other powerful ethnic rebel armies like the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) or the Karen National Union (KNU), who enjoy strong US backing through their church connections, now start their own offensives, the Burmese military junta may have too much on its plate to handle. Not to underestimate the growing hit capability of the Peoples Defences Forces comprising of majority Bamar youth groups who moved away from peaceful protests and started armed rebellion after the brutal suppression of the 2021 street protests following the coup. Never before in Myanmar’s post-colonial history has its all-powerful army faced such a military challenge from a plethora of ethnic rebel groups backed by an exile National Unity Government that is not without its armed groups like the PDF and smaller resistance forces in and around the Bamar homeland.

The ASEAN’s peace diplomacy based on its 5-point consensus has clearly failed to make any headway and India, with its wait-and-watch approach on Myanmar, has clearly missed a huge opportunity to initiate a peace process by leveraging its links and credibility with all major warring stakeholders. Delhi may still try out its peace outreach in Myanmar through a Gandhi peace mission that was proposed by this writer and other top Myanmar-watchers, but after the runaway success of the Brotherhood Alliance’s offensive, other rebel armies and the NUG may be less than willing to open a dialogue, at least until such time they have gained enough territorial control to impose a comprehensive federal solution in Myanmar.

Continuous conflict in Myanmar will not help northeast Indian rebels retain their bases and local allies (mostly Burmese military commanders in desperate need of armed support) but also put pay to Indian efforts to operationalise key connectivity projects like the Kaladan Multi-modal corridor or the Golden Quadrilateral that envisioned seamless overland connectivity between northeast India and rest of Southeast Asia. If the Myanmar civil war intensifies, India’s Act East overland outreach that aims to situate the country’s under-developed Northeast at the heart of Delhi’s engagement with the Tiger Economies of Southeast Asia will remain a pipedream. So it is time, South Block focuses less on a possible Indian peace diplomacy in Ukraine and Palestine and more on ameliorating the conflict in Myanmar.