Philippines-US Bilateral Defense Guidelines: Updating An Alliance Does Not Displace Diplomacy – Analysis

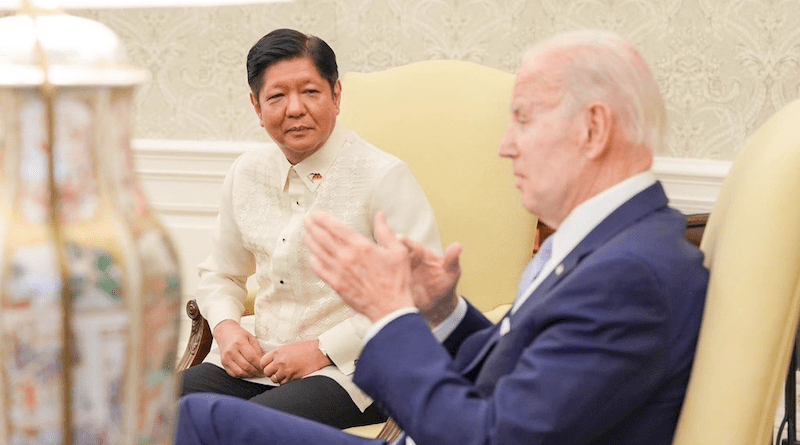

In May, the Philippines and the United States issued new Bilateral Defense Guidelines. They were released on the third day of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s second visit to the U.S. The guidelines help update the alliance without going through the tedious process of amending the text of the mother treaty, the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT), which Manila requested to be reviewed to factor in changing times.

The guidelines reiterate the foundations of the septuagenarian alliance, outlined later dialogue and consultation mechanisms (e.g., Bilateral Strategic Dialogue since 2011 and Two-Plus-Two Ministerial Consultations since 2012), and documents like the Joint Vision for a 21st Century United States-Philippines Partnership in 2021. They bear on shared risk appreciation, Philippine military capacity buildup, and the Taiwan Strait hotspot. That said, they do not narrow both sides’ options to pursue their respective national interests and foreign policy goals.

Cornering a market or developing a homegrown defense sector?

The guidelines presage greater U.S. involvement in Manila’s military modernization. The two allies will “coordinate closely on the Philippines’ defense budget planning, including through the development of a Security Sector Assistance Roadmap to identify priority defense platforms and force packages over the next five years.” Both sides will “prioritize the procurement of interoperable defense platforms in line with the MAA [Military Assistance Agreement] and sourced from various U.S. programs, including but not limited to Foreign Military Financing, Foreign Military Sales, and Excess Defense Articles in addition to the Philippines’ national defense procurement and funding initiatives.”

The move may prioritize U.S. aerospace and defense companies over their rivals, allowing them to corner the Philippine arms market. It may, for instance, tip the balance in favor of American F-16s vis-a-vis Swedish Saab Gripen in the country’s multirole fighter program. Hence, it may reverse nascent attempts to diversify Manila’s defense inventory. Under the former Duterte government, the Philippines became the first foreign buyer of BrahMos cruise missiles co-developed by Indian and Russian defense outfits. It also became the first foreign market for Turkey’s T-129 ATAK helicopters. The country also bought a fleet of six Embraer A29 Super Tucano turboprop light attack aircraft, becoming only the second Southeast Asian operator of the Brazilian platform after Indonesia. Competitive cost and a desire not to be too beholden to one or a limited pool of suppliers were key motives behind this diversification drive. An acquisition process skewed in favor of one country vendor from the get-go may dissuade competitors and diminish Manila’s bargaining position in securing the best bang for the buck, which is crucial given limited post-pandemic fiscal space.

The alliance must dispel the notion that interoperability comes with a steep price tag. Less new but upgraded platforms can be explored. Japanese, Korean, and other NATO member alternatives can be considered. More than being a salesman, Washington should be a genuine partner in Manila’s Self-Reliant Defense Posture (SRDP) program, a decades-long aspiration dating back to the time of the incumbent president’s father, the late strongman Marcos Sr. The Security Sector Assistance Roadmap can dock with SRDP to chart a pathway for Manila to develop its own defense industry. Other U.S. Asian allies and partners like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have robust military-industrial complexes. This enabled them to meet much of their own security requirements and contribute their fair share of the burden to keep regional peace and stability. Given the country’s strategic location in the First Island Chain, the underdevelopment of the Philippine defense industry is a liability for Manila and the region.

The U.S. can do more than dispatch vintage vessels or aged cargo aircraft to its longstanding Southeast Asian ally. This is short-term and does not leave a good lasting impression. The five-year horizon of the roadmap and the ten-year duration of the renewed Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) will be a critical timeline in Manila’s long-overdue plan to grow its indigenous defense-civilian sector. Some leads can be pursued. For instance, the ex-Hanjin shipyard in Subic that American private financial firm Cerberus took over last year should invite competent industrial partners from U.S. or other allied countries to build Philippine naval, coast guard, or merchant ships. More than four years have passed, but work on the shipbuilding facility, the world’s fourth largest in its heydays, has yet to resume. Such defense industry cooperation will produce enduring economic and security dividends for both sides and the region.

Rising minilaterals and responding to gray zone threats

The guidelines also showed the alliance’s view of emerging security minilaterals. Both sides will “prioritize trilateral and other forms of multilateral cooperation based on common issues of shared concern and interest.” Manila’s positive views towards U.S.-led arrangements like Quad and AUKUS are instructive in this regard. Both sides will also “identify appropriate opportunities for third-party participation and observation from other nations’ armed forces to bilateral U.S.-Philippines defense activities.” The debut Philippines-U.S.-Japan coast guard exercises and Tokyo’s burgeoning participation in PH-U.S. bilateral military exercises including Balikatan, Salaknib, Kamandag, and Sama Sama, are prime examples.

The guidelines also recognized the growing threats below the threshold of an armed attack that can readily activate MDT obligations. Both sides “endeavor to build interoperability and cooperation in both conventional and non-conventional domains while taking into account asymmetric, hybrid, and irregular warfare and gray-zone tactics as well as artificial intelligence and other emerging technology areas.” Beyond lighting the gray-zone, more real-time information sharing and support to shore-up maritime patrol and resupply capabilities to its administered features in the Kalayaans (Spratlys) can strengthen Manila’s posture in the South China Sea flashpoint. Uncrewed air and underwater vehicles that security clusters like AUKUS can produce can enhance the country’s maritime domain awareness. Assistance to boost cybersecurity capacity can help protect critical infrastructure from potential attacks.

Cross-Strait hotspot and independent foreign policy

Upgrading the alliance need not strain ties with neighbors or limit diplomatic maneuver. Both sides “reaffirm their mutual obligations under international law to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state without prejudice to the inherent right of self-defense recognized in the United Nations Charter” (emphasis supplied). This passage keeps with Marcos Jr.’s statement that he will not allow EDCA bases, including three new sites in northern Luzon opposite Taiwan, to be used for offensive purposes. The subtext is clear – the alliance is partial against any cross-Strait change achieved through non-peaceful means.

Finally, the Philippines and the U.S. “remain committed to settling disputes or differences by peaceful means, as well as maintaining regional and global peace and security through dialogue and practical cooperation leveraging bilateral, minilateral, and multilateral platforms.” Both sides also “retain the ability to pursue, consistent with international law, their respective national interests and independent foreign policy goals, including developing relations or cooperation with other countries and other entities” (emphasis supplied). Days after Marcos’ second trip to Washington, U.S. and Chinese delegations met in Vienna. Early in June, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Kritenbrink and National Security Council Senior Director for China and Taiwan Affairs Sarah Beran traveled to Beijing. Just recently, Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited China. On Manila’s part, a PLA Navy training ship on a goodwill visit was welcomed. The country remains committed to the Bilateral Consultative Mechanism with Beijing and the ASEAN-China Code of Conduct negotiations.

Modernizing the alliance to face new risks and threats does not replace dialogue and diplomacy to address differences. That the guidelines reflect this is noteworthy.

This article was also published at China-US Focus