Was Humpty Dumpty The First Promoter Of AI? – OpEd

By Peter Isackson

In the US, the rhetoric keeps intensifying and accelerating in an increasingly desperate attempt to justify the war in Ukraine. According to the best estimates, nearly half a million people have died. In the words of John Mearsheimer, the war can only leave Ukraine “wrecked” as a nation, whatever the outcome on the battlefield.

But like any ill wind, this one blows some good. This war clearly hasn’t wrecked the US defense industry. On the contrary, its tenors openly celebrate the conflict. It has handsomely boosted their already thriving activity. The war offers the additional opportunity to test the efficacy of new weapons on human guinea pigs, something that can never be achieved in peacetime.

The war hasn’t wrecked the prospects of BlackRock and other Wall Street giants, who are expecting to profit from whatever pickings are available when the swords flashing today find their ways into the proverbial ploughshares.

The latest rhetorical trope bandied about by multiple politicians and pundits consists of describing US support for the war as an “investment.” Good investments not only produce profits but prove that capitalism is always getting things done. Senators Mitt Romney, Richard Blumenthal and Mitch McConnell, among others, have all made public statements praising the economic sense of spending tens of billions of dollars on Ukraine’s war. The Bill Kristol-led group “Republicans for Ukraine” has released a TV ad that contains this vibrant pitch:

When America arms Ukraine, we get a lot for a little. Putin is an enemy of America. We’ve used 5% of our defense budget to arm Ukraine, and with it, they’ve destroyed 50% of Putin’s Army. We’ve done all this by sending weapons from storage, not our troops. The more Ukraine weakens Russia, the more it also weakens Russia’s closest ally, China. America needs to stand strong against our enemies; that’s why Republicans in Congress must continue to support Ukraine.

The ad describes Putin as an “enemy.” Putin’s army has invaded Ukraine, but does that make him an enemy of the US? China has not attacked the US or invaded a country the US is particularly fond of. Yet Senator Ted Cruz can affirm that “our enemies across the globe, including, in particular, China, are watching carefully what happens in Ukraine.”

An enemy is not simply a person or nation that another nation does not like or whose behavior it does not countenance. If that were so, every nation would be an enemy, which is what Ted Cruz seems to be suggesting.

The term “enemy” has historically been used to designate a nation that directly threatens the survival or well-being of another nation. All nations can be rivals. Some may even have adversarial opinions or ideologies. But only adamantly bellicose nations — literally governments committed to a paranoid ideology — can routinely refer to rivals as enemies.

Can the case be made that Russia threatens the survival or well-being of the US and therefore deserves to be called an enemy? More broadly, does it make sense to call a murderous war an investment, especially when one of the possible outcomes is nuclear war? Is there any historical precedent for such reasoning?

I wondered how ChatGPT would respond to these questions. The result hardly surprised me. But it did give me some new clues about the nature of AI’s supposed reasoning faculties.

On the question of what it means to be an enemy, here is its response:

The use of the term “enemy” in the context of international relations is a matter of perspective and often depends on the specific goals and interests of a nation. In the statements you’ve provided, individuals and groups are characterizing Putin as an “enemy of America” based on their assessment of his actions and policies. It’s important to note that this is a subjective view and a rhetorical device used to convey a sense of opposition to Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

The term “enemy” in international relations can carry different connotations and may not necessarily mean that one country poses an existential threat to another. It often implies significant political, diplomatic or military opposition, as well as fundamental differences in interests or values. Russia’s actions in Ukraine are seen by many as a violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and a challenge to the post-Cold War international order, which has led to strong condemnation and characterizations like “enemy” from some quarters.

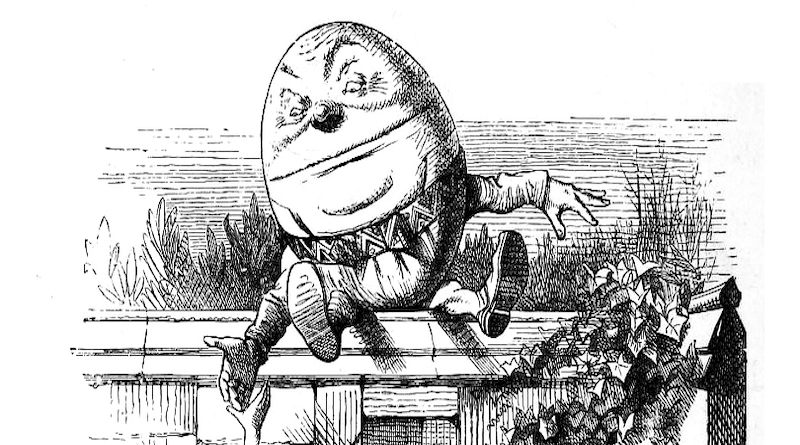

Let’s consider the first statement: “The use of the term ‘enemy’ in the context of international relations is a matter of perspective and often depends on the specific goals and interests of a nation.” Is that fundamentally different from what Humpty Dumpty said in responseto Alice? “‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean–neither more nor less.’”

Historians and linguists alike should be interested in defining what historical and cultural context allows the meaning of “enemy” to shift in this way. In this case, to simplify, consistently with ChatGPT’s explanation, it is about the “goals and interests” of the US, not as a nation, but as the global hegemon. Neither France, Germany, Italy or any of the other NATO countries considers Russia their enemy. They have been coaxed into accepting NATO’s position in solidarity with Ukraine, but they do not consider Russia their enemy. Only the US does, which of course, unlike Europe, benefits from being separated by two oceans from Russia.

In the second paragraph, however, ChatGPT does acknowledge that the idea of enemy is related to “a challenge to the post-Cold War international order.” For that to make sense, we must suppose that the US can be identified with the post-Cold War international order. In other words, because it enforces the global order, it can assume Humpty Dumpty’s liberty of calling anyone who disturbs that order an enemy.

Like most US politicians and pundits — to say nothing of the media — ChatGPT cannot be bothered with historical reality or complex geopolitical relationships. It prefers the Humpty Dumpty approach. An enemy is anyone with whom there exist “fundamental differences in interests or values.”

So what about the idea that supporting a violent war, with no stated objective and an apparent taste for allowing it to last “as long as it takes,” can be called an investment? Faithful to its Humpty Dumpty logic, ChatGPT explains:

As for characterizing expenditures on the conflict in Ukraine as an “investment,” this is also a matter of rhetoric and perspective. People who argue that it’s a “good investment” may be emphasizing the potential benefits of supporting Ukraine, such as promoting stability, countering Russian aggression and advancing democratic values in the region. However, whether it is an actual investment with a guaranteed return is a matter of debate.

If it’s a matter of debate, why not have the debate? ChatGPT supposedly never takes sides, so that isn’t going to happen. But suggesting that fueling a murderous war is “promoting stability” reveals that it has already taken a side and assumed a point of view that says war fosters stability. To make such a suggestion to justify US support of a war of attrition taking placing on the other side of the world means ChatGPT has taken the side of absurdity.

ChatGPT ended this line of reasoning with the following conclusion:

Ultimately, the characterization of terms like “enemy” and “investment” in the context of international relations is subjective and shaped by the perspectives and objectives of those making such statements. Different individuals and groups may use these terms differently, and the debate over their appropriateness is a part of the broader discussion about foreign policy and national security.

In other words, this officially “large language model” does not care a whit about how language is used. People “may use these terms differently.” Because they choose to do so and implement policies on that basis, people die and nations are wrecked. But that’s OK because we are free to “debate over their appropriateness” as “a part of the broader discussion about foreign policy and national security.” There is a debate about the distortion of meaning, but only because that meaning has already been distorted. The sad fact is that there was no debate or even opportunity for debate before the fateful policies were enacted.

About the author: Peter is Fair Observer’s chief strategy officer. He is an author and media producer who has worked on ground-breaking projects focused on innovative learning technology. For more than 30 years, Peter has dedicated himself to innovative publishing, coaching, consulting and learning management. As a publisher, he has developed collaborative methods and revolutionary software tools based on non-linear logic for soft skills training. He has authored, produced and published numerous multimedia and e-learning products and partnered with major organizations such as the BBC, Heinemann and Macmillan.

Source: This article was published by Fair Observer