War In Ukraine: Implications For European Security – OpEd

Putin’s ongoing “special military operation” in Ukraine has breached all strands of fundamental international law emphasizing state sovereignty, non-intervention in other states’ internal and external affairs, and respect for human rights established in the aftermath of the Second World War.

As a shift in the world order in the mid-twentieth century, when victorious Allies put forth a new global cooperative security regime in place in order to prevent such cataclysmic conflict from ever repeating in the future. However, preceding events in global politics marked by ideologically rooted geopolitical rivalries between the Capitalist-West led by the US and the Communist East spearheaded by the USSR made many of the post-war international arrangements for peace building and conflict resolution indecisive, but succeeded to deescalate high scale tensions might have led to any all-out nuclear Armageddon between superpowers; for instance, Cuban missile crises in 1962, prompted realization amongst nuclear-armed states to initiate international negotiations for arms control and disarmament treaties.

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) was the upshot in this regard, signed in 1968 to legitimize the nuclear power status of P5 members and prohibits the sale, transfer, and development of nuclear explosive materials and technology for non-nuclear NPT members with belligerent intentions. Following that period in 1991, the disintegration of the USSR left three states: Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan with the largest nuclear stockpiles which threatened the horizontal proliferation of nuclear weapons in utter disregard of NPT provisions. However, in 1994, the Budapest memorandum was agreed upon therein the US, UK, and Russian Federation accorded security assurance to Ukraine in exchange that the latter would relinquish the world’s third largest nuclear weapons stockpile and thereby joins the membership of NPT as a non-nuclear state.

The question of the Russian strategic interests in European security predates the Ukrainian crisis. Fundamental principles and values upon which the contemporary security order in Europe was established were the outcomes of intense multilateral negotiations conducted in a bid to concede détente in the early 1970s. The first summit of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) in Helsinki, in 1973, and then subsequent diplomatic interactions under the same agenda helped signed a political declaration of intent, known as the Helsinki Final Act 1975.

This act established non-binding obligations upon all signatories to abide by the unavoidability of post-Second World War national frontiers in Europe; States to refrain from the threat or use of force; aim at peaceful settlement of disputes; respect human rights and basic freedoms; ensure equal rights and self-determination of their peoples, and fulfill their legal responsibilities under international law. Despite the wide acceptance of the CSCE goals and objectives, the normative and institutional structure of Europe based upon the aforementioned values and principles witnessed EU and NATO ascendency in all spheres of security and economic affairs bent upon promoting liberal democratic ideas across the region. In the immediate aftermath of its integration, Russia was mired in domestic instability unable to challenge the post-cold war order pre-disposed to the Euro-Atlantic partnership, therefore, perceived as aiming to marginalize it.

Therefore, Russia continued to contest the idea of NATO and EU symbolizing pan-European international society; multiple endeavors for reconciliation via bilateral consultations over the security governance failed largely for the reason that NATO continued its expansion in Eastern Europe with security reassurances to members against any anticipated threat from revisionist Russia. The security concerns about NATO expansion eastward and thereafter strategic deployments nearby its immediate territorial boundaries replicate the possibility of crises same as occurred in Cuba in 1962.

The enlargement of the EU and NATO-led European order in post-communist Europe was perceived by Russia as part of Brussels’s vicious geopolitical advancement to consolidate its own sphere of influence in Eastern Europe at the expense of the USSR’s historical prestige. Therefore, the political elite in Russia continued to feel contained and thus resisted an attempt at the imposition of western liberal values and norms in former satellite states. The same motivation was behind the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 when Yanukovich’s regime crumbled as a result of a massive Euromaidan uprising demanding closer relations with the European Union. The event was interpreted by Moscow as Europe trying to compel Ukraine to make a hard choice between east and west, which further aggravated the internal differences. Moreover, a vast array of sanctions that followed the Crimean annexation, however, intended to punish Moscow but instead made its political stance firm that the west aim to destabilize Russia to the extent of disintegration.

The Feb. 24 Putin invasion under the pretense to “demilitarize and de-Nazify Ukraine” and to protect the Russian ethnic minority in Ukraine that accounts for 17.3% of the total population (census 2001), the majority of them residing in the bordering far eastern oblasts of Donetsk and Luhansk, from alleged genocide by Ukrainian government was justified by him referencing to NATO’s military intervention in Yugoslavia and support for Kosovo in 1999. Nonetheless, Russia’s war policy is much more than simply a concern for humanitarian causes. Ukraine’s intention to join the western military alliance, NATO is a nightmare that has fueled the security dilemma in Moscow as it will allow military installations, troops stationing, and deployment of strategic weapons in the immediate neighborhood of Russia. Scholars and academics fear that enforcing “neutrality status” on Ukraine would be akin to letting Kyiv into Moscow’s subservience. However, it is yet to be seen if Putin agrees to anything less than Ukraine not joining the western alliance or if this would embolden him more to pursue a challenging stance against overall European security architecture.

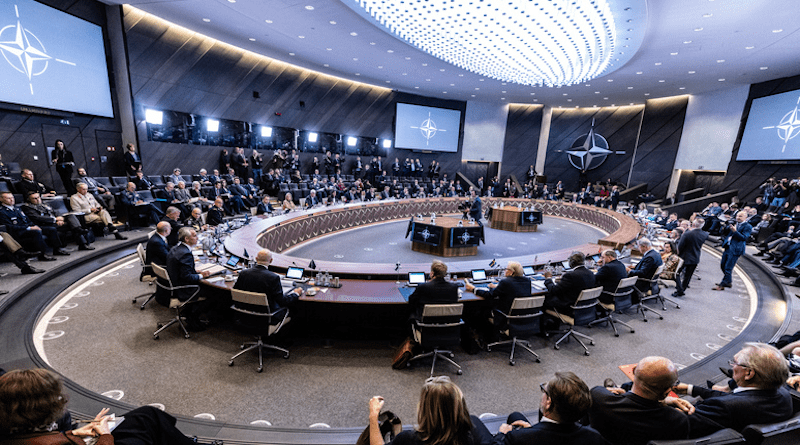

A Ukrainian crisis has confronted the mandate of dominant actors of European security which includes NATO, EU, Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), and the Council of Europe. All these organizations act more as guarantors of European values and norms, which are core to their foundation than merely security players. So far, one has witnessed reluctance on NATO and EU part to broaden the security parameters to draw a red line that does not only count in member states but also regional partners with same value-based system. Internal divisions have been laid bare as national interest takes precedence over collective objectives. European countries heavily reliant on Russian energy imports faced domestic instability followed by a high cost of living. Nonetheless, Russian aggression has prompted the need for alliance consolidation and any prospects for the survival of post-Cold war European security architecture are contingent upon the uncompromised conclusion of the Russo-Ukraine conflict.

Muhammad Nabeel is a master’s student at the Department of International Relations, University of Karachi.