The Palestinian Nakba – Analysis

The origin and meaning of Nakba

The Nakba, which means “catastrophe” or “disaster” in Arabic, refers to the exodus of Palestinians following the 1948 war between Israel, which had just proclaimed its independence after the end of the British mandate over Palestine, and a coalition of Arab countries.

The concept of the Nakba was first coined by the famous Syrian intellectual Constantin Zureiq قنسطنطين زريق, born in a Greek Orthodox home in Damascus, and the term entered the Arab political dictionary before penetrating consciences the world over.

In the summer of 1948, at the age of 39, sensing that the debacle of the Arab armies against the troops of the young Israeli state was irremediable, this thinker, then Professor of History at the American University of Beirut (AUB), conceived a short essay entitled Ma’na al-Nakba (“the meaning of the catastrophe”). Written in a few weeks in a hotel in the Broumana district of Beirut, the opuscule was an immediate success, and was reprinted several times and translated into English.

“The defeat of the Arabs in Palestine is not a passing calamity or a simple crisis, but a catastrophe (Nakba) in every sense of the word, the worst to have befallen the Arabs in their long and drama-filled history”, Zureiq asserts at the start of his book, the manuscript of which, is kept in the archives of the American University of Beirut.

The United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine in 1950 estimated the number of refugees at 711,000 (and estimated 800,000 to 900,000 refugees registered with UNRWA in a 1961 report). 550,000 to 600,000 according to a post-war Israeli government estimate. Efraïm Karsh, calculating the difference between the Arab population before and after the war, deducts between 583,000 and 609,000 refugees, and according to some Arab historians (Abu Sitta or Abdel-Azim Hammad) the figures are between 800,000 and approximately 900,000 refugees.

According to humanitarian organizations at the time, this forced exile involved 900,000 Palestinians. At the time, 900,000 people represented around 85% of the total population. Some went to the Gaza Strip – which today is made up of 80% of people descended from refugee families – others went to the West Bank, and still others went further afield, to Jordan, Lebanon or Syria.

Some Palestinians have also remained on Israeli territory. They call themselves the Palestinians of Israel or the Palestinians of the 1948, but they have really been a minority, representing today 20% of the Israeli population.

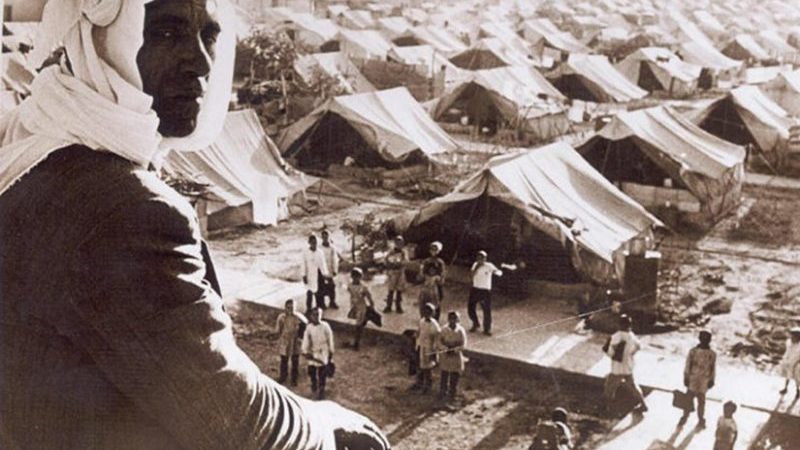

Some 40% of these Palestinian refugees were housed in camps, initially set up by humanitarian organizations such as the Red Cross and the Quakers in Gaza. These camps were later taken over by UNRWA, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East.

A large number of these refugees – 5.6 million – found asylum in neighboring Arab countries, mainly Jordan. Others have taken up residence in Lebanon and Syria, or in the occupied territories. Some members of the Palestinian diaspora have settled in more distant lands, notably the United States and South America.

In 1952, the majority of refugees arriving in Jordan were granted Jordanian nationality, with the same citizenship rights as local residents. The same was true in Syria, with one difference: they did not have Syrian nationality, which was also a way for Syria to maintain the idea of the possibility of return.

In Lebanon, the rights of refugees were much more restricted. They were not granted nationality, and a whole series of professions were forbidden to them – as is still the case today.

The shock of uprootedness is strong, as a large part of the Palestinian population was very rural. For these people, who lived off the land, it is an extremely deep trauma to find themselves in refugee camps for a large proportion of them, or to be exiled elsewhere, in neighbouring countries.

This trauma is commemorated every year on May 15. A date that corresponds to that of the creation of the State of Israel. Although we know that even before the creation of the State of Israel, and even before the Arab armies went to war, half the people had already been displaced. So, in the end, a symbolic date is chosen, but it doesn’t correspond to the population movements, of course, which actually took place between 1947 and 1949.

The Nakba in history

According to a secret intelligence document from the Haganah – the main illegal Jewish army before the creation of the Israel Defense Forces (Tsahal) at the end of May 1948 – which Israeli historian Benny Morris found in the archives of the State of Israel: by May 15, 1948, almost 400,000 Palestinians had already left the territory. And Haganah spies tell us that 73% did so because of the actions of the Jewish armed forces and the massacres that took place at that time. The rest were either, at 22%, fears of the dissolution of Palestinian society, and, at 5%, calls for local departures by Palestinian militia leaders.

Walid Khalidi, a Palestinian historian, denounced this “politico-military expulsion plan” as early as 1961, in his essay ‘’Plan Dalet: Master Plan for the Conquest of Palestine.’’ The Israeli authorities’ strategy was in fact protean, and also took the form of “psychological warfare”.

“One of the favorite themes was the spread of disease on the Arab side. On February 18, Radio Haganah announced that cases of smallpox had been detected in Jaffa, following the arrival of Syrians and Iraqis. On the same day, it revealed that among the dead and wounded Arabs who had fallen in battle, several were suffering from “contagious diseases”’’, explains Walid Khalidi.

The Palestinians’ fear is also based on massacres, such as that of Deir Yassin, perpetrated by the Irgun – an armed Zionist organization – and the Lehi, on the night of April 9 to 10, 1948. 250 women, children and elderly inhabitants of this small village near Jerusalem were slaughtered. The Israeli conquest of Arab lands continued. Two Arab towns fell before the proclamation of the Jewish state: Haifa on April 22 and Jaffa on May 13. The strategy of inducing departure was used by the Israelis, as Irgun leader Menachem Begin himself acknowledged in his book The Revolt (1973):

“The Arabs of Eretz-Israel were seized with panic (…) and began to flee in terror (…). The legend of Deir Yassin helped us to conquer Haifa“. “In the space of a week, 50,000 Arab inhabitants were expelled,” comments Walid Khalifa, referring to Haifa’s fall to the Zionists.

The Palestinian exodus became massive after May 14, 1948 and Israel’s declaration of independence, which triggered the first Arab-Israeli war. With the creation of the State of Israel and the strengthening of the young Jewish army’s military capabilities, this tactic of encouraging people to leave turned into a deliberate strategy of expulsion. The result: 300,000 more Palestinians forced into exile. The case of the twin towns of Lydda and Ramleh, in July 1948, offers the most spectacular example of the new methods.

The future Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin, acknowledges this use of force in his Memoirs. These extracts were censored in the final version of Rabin’s Memoirs, but reproduced in the New York Times of October 23, 1979.

“We were walking outside alongside Ben Gourion. Allon repeated the question: “What should we do with the population?” Ben Gurion waved his hand in a gesture that meant “Drive them out.” Allon and I took counsel. I agreed with him that it was essential to drive them out. We put them on foot on the road to Bet Horon (…) the people of Lod did not leave voluntarily. There was no other way but to use force and warning shots to coerce the inhabitants“, he wrote after the conquest of Lydda (Lod in Hebrew), in July 1948.

Faced with the scale of the Palestinian exodus, some Israeli ministers worried about a decline in Zionist prestige. “In a military situation that was still precarious, the young state could not alienate international sympathy“, he analyzed.

Aharon Cizling, the Minister of Agriculture, told the Council of Ministers on November 17, 1948:

‘’I couldn’t sleep all night. What is happening hurts my soul, that of my family and all of us (…). Now the Jews, too, are behaving like Nazis, and my whole being is shaken.’’ Remarks transcribed by historian Tom Segev, in 1949: The First Israelis.

The myth of flight

For a long time, the expulsions of Palestinians have been denied by the Israeli authorities and the Israelis themselves. For Israel, the Palestinians fled because they answered the Arab countries’ call to leave. Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi describes this official version of history as “propaganda”.

“The myth that the 1948 Palestinian exodus was triggered by orders from Arab leaders – an antiphon used by the official Israeli version of the 1948 war to absolve itself of any responsibility for the refugee problem – has a long life. Israel’s defenders bring it up again as soon as they try to blame the Palestinians for their fate“, he denounces in Nakba (1947-1948).

How then to justify the massacres perpetrated in Arab towns? “According to Dominique Vidal in his book Comment Israël expulsa les Palestiniens? (How Israel expelled the Palestinians), not only did the heads of the Jewish Agency, and later the Israeli government, not plan any eviction, but the rare massacres to be deplored – starting with Deir Yassine on April 9, 1948 – were carried out solely by extremist troops affiliated with Menachem Begin’s Irgun and Itzhak Shamir’s Lehi.

This version of events is contested by Palestinian historians such as Walid Khalidi, but initially remains confined to the Arab world:

“One of the central themes of the Zionist version of events between November 1947 and May 1948 is that orders were broadcast to the Arabs to leave the country, in order to clear the way for the regular Arab armies. I have found no evidence of this allegation in the Zionist sources of 1948, although it would have been obvious to find it there at the time. On April 23, 1948, for example, Haganah radio gave a detailed account of the flight of the Arabs from Haifa in response to the Syrian delegate to the United Nations who accused them of committing atrocities against the Arabs. Radio Haganah did not mention any orders in its account of the Arab flight. In early May 1948, King Abdullah of Jordan accused the Zionists of expelling the Arabs from their homes. On May 4, Radio Haganah denied this, but did not mention any Arab order for the Arabs to leave”, he details in Nakba (1947-1948).

A new version of history with the opening of Israeli archives

It was not until the late 1970s that a new historiography began to challenge this Israeli version of history. It was led by a generation of so-called “new Israeli historians”, such as Benny Morris, Tom Segev and Avi Shlaim. Thirty years after the creation of the State of Israel, they finally have access to the archives and find no appeals from Arab countries.

In Israel, there’s a peculiarity: the archives begin to open thirty years after the events. In other words, in 1978, the state and army archives on the 1947-1949 war began to be opened. A whole generation of historians pounced on these texts and learned that there had been no flight, no departure at anyone’s beck and call. There was a massive expulsion, the bulk of which was due to the action of Jewish forces during the war.

The Nakba repeats itself

In a 2011 article entitled “La Nakba continuelle”, Lebanese writer Elias Khoury, a fellow member of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), offered a critical rereading of Constantin Zureiq’s seminal work.

“What he didn’t understand at the time was that the Nakba is not an event but a process,” exposes the novelist, whose latest work, Les enfants du Ghetto: je m’appelle Adam (Actes Sud, 2018), focuses on Israeli Arabs, the descendants of Palestinians who didn’t flee in 1948. “Land confiscations have never stopped. We’re still living in the Nakba era,” continues Elias Khoury.

After leaving the AUB in the late 1950s, Zureiq, who already held a doctorate in history from the American University of Princeton, defended a second thesis, in literature, at a university in Michigan. The theorist of Arab nationalism pursued his career in Kuwait, Sudan and at UNESCO, while publishing numerous works criticizing the immobility of Arab societies. He died in 2000 in Beirut.

The Nakba officially ended with the last Arab-Israeli armistice, in this case with Syria, on July 20, 1949. To commemorate the exodus of their people between 1947 and 1949, the Palestinians chose May 15. For Palestinian refugees, the Nakba represents a temporal marker commemorating a national moment characterized by uprooting. Today, many historians agree that the Nakba continues, albeit in a different form. The term is admittedly inappropriate, as it refers to the expulsions that preceded and followed Israel’s declaration of independence. But it can be used for “pedagogical reasons”, to refer to the current situation of the Palestinians, which resembles that of the first refugees.

The Nakba that continues is in fact the dispossession of the Palestinians from their land. The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) now counts over five million Palestinian refugees. This ongoing Nakba is in fact the key to the whole Israeli-Palestinian problem: Imagine a people more than half of whom are abroad, outside their own land. Obviously, this is a major problem that has been at the heart of this conflict for 75 years now, an “open wound” for the Palestinian people.

Another stumbling block in the conflict is the return of refugees. On December 11, 1948, the United Nations passed a resolution stating that “refugees who so desire should be permitted to return to their homes as soon as possible and to live in peace with their neighbors, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those who decide not to return to their homes“. On May 11, 1949, the Israeli government endorsed this resolution at the Lausanne Conference. The following day, Israel was admitted as a member of the United Nations. But since then, the resolution has never been respected.

The Israelis have never accepted any return. It was ethnic cleansing. For the State of Israel, which came into being in 1948, to be a Jewish state, it needed a majority of Jews. Consequently, the Palestinians had to be expelled. Otherwise, they would have had a Jewish state with a Palestinian majority.

You can follow Professor Mohamed Chtatou on Twitter: @Ayurinu