Hague Court Favors Pakistan In Water Treaty Arbitration, Rejects Indian Objections – OpEd

By Asfandiyar

Pakistan’s view of the pleading ‘court of arbitration’ as an appropriate forum for conflict resolution has been vindicated.

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague rejected India’s objections to its assumption of jurisdiction in an arbitration case between the neighboring countries regarding the Kishanganga and Ratle hydroelectric projects, in a major victory for Pakistan. The PCA found in favor of Pakistan, ruling that it was the competent authority to resolve the Kishanganga dispute between Pakistan and India. However, India deemed the arbitration proceeding to be unconstitutional because a neutral expert was also investigating the matter, and the World Bank-brokered contract forbids parallel proceedings.

“In a unanimous decision, which is binding on the Parties and without appeal, the Court rejected each of the objections raised by India and determined that the Court is competent to consider and determine the disputes set forth in Pakistan’s Request for Arbitration,” the statement said.

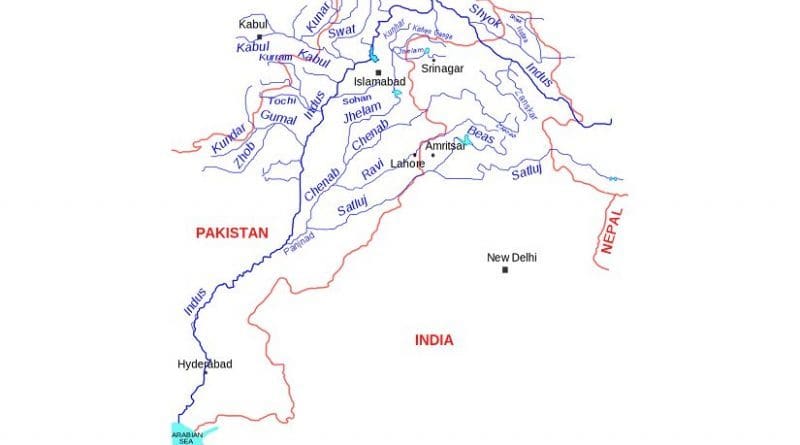

For decades, the South Asian neighbors have fought over hydroelectric projects on the joint Indus River and its tributaries, with Pakistan claiming that India’s projected hydropower dams in upstream areas will reduce flows on the river, which supplies 80% of Pakistan’s irrigated agriculture. The disagreement stems from Pakistan’s concerns about India’s building of the 330MW Kishanganga project on the Jhelum River and plans to develop the 850MW Ratle Hydroelectric project on the Chenab River in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK).

Pakistan sought resolution of the dispute through PCA arbitration procedures in 2016, prompting India to propose that the World Bank appoint an impartial expert under the terms of the 1961 Indus Waters Treaty (IWT). Islamabad has approached the PCA after voicing concerns about the Kishanganga project in 2006 and the Ratle project in 2012 at the Permanent Indus Water Commission in order to resolve the disputes on a government-to-government basis. Pakistan requested the formation of the PCA due to systemic issues requiring legal interpretation. In response, India requested the appointment of an impartial expert through a formal dispute resolution process. The submission of a belated petition for the resolution of concerns made by Pakistan demonstrated India’s traditional ill faith, according to a statement.

The Indus Waters Treaty establishes two dispute resolution forums: the Court of Arbitration, which handles legal, technical, and systemic concerns, and the Neutral Expert, who can only address technical matters. According to sources, Pakistan proposed the setting up of a Court of Arbitration because it had systemic issues that required legal interpretation. India replied to Pakistan’s official dispute resolution mechanism with its own belated request for the appointment of an impartial expert, which Islamabad claimed demonstrated New Delhi’s typical ill faith.

Fearing conflicting conclusions from two simultaneous processes, the World Bank stopped the proceedings for establishing a court of arbitration or appointing a neutral expert on December 12, 2016 and encouraged both countries to negotiate mutually for a common forum. However, Pakistan and India were unable to reach an agreement, and the World Bank lifted the suspension after six years — during which India finished the Kishenganga project — and established a court of arbitration and appointed a neutral expert. Pakistan is participating in both fora; by contrast, and in typical bad faith, India has boycotted the Court of Arbitration. In such a case, the court can and is proceeding ex parte.

Following the PCA judgement, Pakistan’s Foreign Office stated that it was completely committed to implementing the Indus Waters Treaty, including its dispute resolution process.

Arindam Bagchi, an Indian foreign ministry official, on the other hand stated that India’s “consistent and principled position has been that the constitution of this so-called court of arbitration is in contravention of the clear letter and spirit of the Indus Water Treaty.”

India raised six objections, including that i) the court of arbitration’s constitution is illegal, ii) the court lacks the competence to hear the case, and iii) it has not yet been established that the issue of changes in project designs is a dispute that can be resolved at the PCA forum, so it should be taken up by a neutral expert because it is the distinction between Pakistan and India, not the dispute. iv) Pakistan had not met the procedural standards of Articles IX(3), (4), and (5) of the Treaty before beginning these proceedings, v) Article IX (6) of the Treaty barred the court from considering the questions “being dealt with by” the neutral expert, and vi) the procedure for appointing the court of arbitration, outlined in Annexure G to the Treaty, had not been followed in the present case, resulting in the absence of an effectively constituted court of arbitration.

Pakistan has submitted three grievances to the design of the Kishenganga project, claiming that the proposed pond is 7.5 million cubic meters in size and should be one million cubic meters. Pakistan also wants India to elevate the intake by up to 1-4 meters and the spillways by up to nine meters.

According to a Pakistani delegation official, India feared that Pakistan’s case was very strong, and that if New Delhi lost the dispute, it would be unable to build future projects on Pakistani rivers with poundage and spillways. To obstruct CoA proceedings, New Delhi submitted a notice to Pakistan on January 25, asking changes to the Treaty two days before the court hearing on January 27-28.

Pakistan highlighted four concerns about the Ratle Hydropower Plant. Islamabad wants India to preserve the freeboard at one meter, while India wants it to stay at two meters. Furthermore, India wants to maintain the 24 million cubic meter pond, but Pakistan wants it reduced to eight million cubic meters. Pakistan also wants the project’s intake to be elevated by up to 8.8 meters, and the spillways to be raised by up to 20 meters.

India is firm that it now wants to Renegotiate the outdated & unjust treaty of 20th century. This treaty is outdated & archaic, period.

India has rightly said & consistently held that the constitution of the CoA set up by the World Bank on the request of Pakistan in October last year is in contravention of the provisions of the Indus Waters Treaty and has refused to participate in its proceedings.

Following the CoA’s statement Thursday, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) also issued a release saying that India cannot be compelled to recognise or participate in illegal and parallel proceedings not envisaged by the IWT.

The IWT was brokered between India and Pakistan by the World Bank in 1960 and outlines how the two countries will utilise the waters of the six rivers of the shared Indus river system. While the western rivers of the system — Indus, Jhelum and Chenab — fall in Pakistan’s share, the three eastern ones — Ravi, Beas and Sutlej — are to be used by India.

Pakistan has alleged that the two hydroelectric projects violate the IWT and will reduce the water flowing into its territory. The CoA is currently looking at the objections raised by Pakistan over the two projects.

Finally, Pakistan may celebrate bit nothing will improve on ground as it doesn’t take into concern India’s genuine concerns on this 1961 outdated treaty.