As Donald Trump Surrenders To Authorities In NY, Remember Feb 1924: The Trial Of Adolf Hitler – OpEd

Here’s a bit of history that may serve as a warning to those celebrating Donald Trump’s forthcoming trial in New York for violating laws regarding hush money payments, campaign expenditures, business records, and tax filings, as well as his possible trials in Georgia and the District of Columbia for suborning election fraud and inciting violence at the U.S. Capitol.

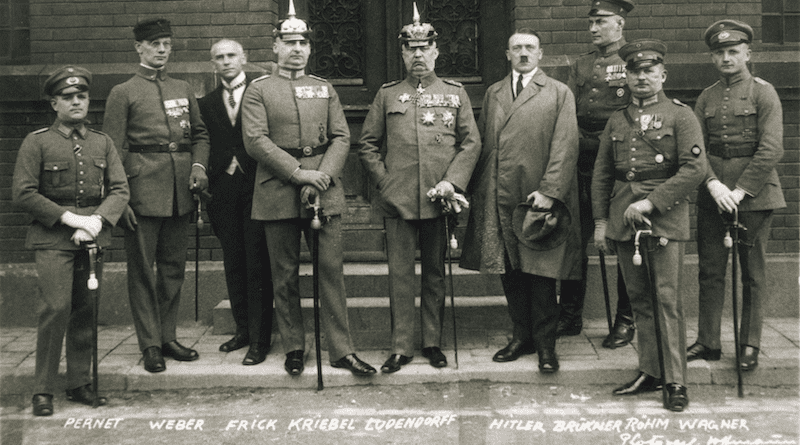

On November 8, 1923, Adolf Hitler, the little-known leader of a little-known political party called the National Socialists, led two thousand followers in an attempt to overthrow the government of Bavaria in Munich, Germany. He intended to use Munich as a base to march on Berlin and overthrow the national government, as Mussolini had recently done in Italy. What has become known as the “Beer Hall Putsch” ended in the deaths of 16 Nazis and 4 police officers, the failure of the coup, and Hitler’s arrest charged with treason.

His trial in Munich in February 1924 made the Nazi leader a national figure and raised his party to international prominence. Hitler’s hours-long speeches in court were reported in the newspapers and quoted everywhere. His pose as a martyr to the cause of German nationalism was widely admired, and his bitter criticism of the Weimar Republic was accepted by many who did not trust “the Berlin Jew government.” Hitler and his comrade, Rudolf Hess, were convicted and sentenced to five years imprisonment, but served fewer than nine months in Landsberg Prison under the lenient conditions reserved for political prisoners. When he exited prison in November, the fascist leader was determined to exploit his new popularity by using legal methods to take power on the national stage.

While in jail, Hitler wrote his political testament, My Struggle (Mein Kampf) with Hess’s assistance. The first edition sold out, and by the time he became Germany’s Chancellor in 1933, a million copies were in print. David King’s thorough book, The Trial of Adolf Hitler (2017), summarizes the matter nicely. “By its end, Hitler would transform the fiasco of the beer hall putsch into a stunning victory for the fledgling Nazi Party. It was this trial that thrust Hitler into the limelight, provided him with an unprecedented stage for his demagoguery, and set him on his improbable path to power.”

Of course, there are important differences between Germany in 1924 and the U.S. ninety-nine years later, and between the embittered war veteran and oratorical virtuoso, Adolf Hitler, and the roguish realtor and sometime TV host, Donald Trump. Karl Marx famously said that history repeats itself twice, “first as tragedy, then as farce,” but in Trump’s case it would be a mistake to consider this reassuring. The former President is a “theater person” who lives for the limelight, and who will surely take advantage of the opportunity to don a crown of thorns and star in his own Passion Play. If he is canny, he will restrain his own impulses to spew hatred (as Hitler did, for the most part, in Munich) and play the role of the long-suffering victim of a heartless, elite-driven State.

Already, Trump is modifying his persona to suit current circumstances. His prosecution in New York clearly has the potential to eliminate one of his major disadvantages as a political candidate: the boredom and malaise generated by his repetitious, ill-tempered rhetoric. He is still the old Donald, but the new situation offers him, as it were, a new role in a new TV series. Even before his surrender to the authorities, his fund-raising operatives were reporting a spectacular increase in political donations, and his potential opponents for the Republican nomination were fading into a dimly lit background.

At this writing, Trump surrendered to federal authorities in Manhattan and later spoke to the nation via television from his own version of Hitler’s Berchtesgaden, Mar-a-Lago. He will no doubt follow up this performance by taking his show on the road and speaking to large audiences around the country. Moreover, if his prosecution survives motions to dismiss, Trump will probably be able to delay the trial until a time that serves his campaign well. If he does go on trial (between campaign appearances!) the odds are that he will either be acquitted outright or serve some minimal, largely symbolic jail time. Meanwhile, other prosecutions, should they occur, will provide him with more on-camera acting opportunities and offer the voting public more televised Entertainment, further spiced by opportunities to participate in high-spirited mass demonstrations.

At worst, these demonstrations could provoke sixties-style street violence, or more serious armed struggle initiated by Far Right militias with or without their hero’s permission. One can argue, of course, that threats of violence or further lawbreaking should not be allowed to deter the legal authorities from doing their jobs. Even so, the Democrats and others calling for Trump’s punishment as a lawbreaker need to think about the unpredictable consequences that otherwise justifiable “law and order” movements can generate. Donald Trump is a dangerous demagogue and a threat to democratic institutions – no doubt about that. His political career should certainly be ended. But prosecuting him for crimes that are either relatively trivial or difficult to prove has the clear potential to make him more dangerous and threatening, not less so.

This seems to me to constitute a genuine dilemma. We would do well, at this juncture in American history, to remember February 1924 and the trial that launched an Austrian buffoon on the road to genocidal leadership. Hitler lost his case in court but won it in the hearts of Germans humiliated by their loss in World War I and enraged by the their government’s failure to solve the grave problems caused by a global depression. America thankfully is not in the grip of this sort of economic collapse. Even so, it seems far better to take the case against Donald Trump to the country and to nominate a candidate that can trounce him at the polls than to furnish him with the equivalent of a theater set where he can act the part of a martyred man of the people.

Symbolic politics can be of real importance. We know that Hitler maintained power in Germany by outlawing and massacring his opponents, but he gained office initially because he understood symbolic politics far better than did his leftist and centrist adversaries, who refused to unite against him. The story of the outspoken citizen who speaks out against a corrupt, all-powerful elite, who understands what ordinary people need and sacrifices his/her own security for them, is not just a “fringe narrative” popular with conspiracy theorists of the Q-Anon sort; it is deeply entrenched in Western consciousness. If you doubt this, re-read Ibsen’s 1883 play, “An Enemy of the People,” or watch almost any Mel Gibson movie. If Trump could write his own script, this is the part that he would most relish since it gives him access to America’s symbol-laden subconscious and permits him to manipulate popular emotions.

Let’s not hand him this script. There are values more important than law enforcement, and there are times when people’s needs for genuine democracy, social equality, and collective compassion take precedence over desires for legal order. Where Donald Trump is concerned, our chant should not be “Lock him up!” but “Defeat him!”

Trusting the people involves a democratic leap of faith, but without it, the democratic goose is cooked. The danger that voters will make a disastrous choice exists, of course; they did this in Germany in 1933. But the danger can be minimized by offering people programs that are actually capable of solving social and economic problems. The problem with going the legal route is not only that it plays the game of demagogues like Trump, but also that it relieves liberals and leftists of the obligation of developing effective programs and gaining popular support for them. Show trials can’t substitute for “show me” politics.

Richard E. Rubenstein is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment and a professor of conflict resolution and public affairs at George Mason University’s Jimmy and Rosalyn Carter Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution. A graduate of Harvard College, Oxford University (Rhodes Scholar), and Harvard Law School, Rubenstein is the author of nine books on analyzing and resolving violent social conflicts. His most recent book is Resolving Structural Conflicts: How Violent Systems Can Be Transformed (Routledge, 2017). This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS)