Decoding Recent Elections In Europe: A Tilt Towards The Right? – OpEd

By Observer Research Foundation

By Ankita Dutta*

The movement of right-wing parties from the margins to the mainstream represents one of the most significant political developments in Europe in the past two decades. While their fortunes in elections have witnessed highs and lows over the years, 2022 represented a key year in this transition in the aftermath of their successes in Italy [Fratelli d’Italia FdI (Brothers of Italy)], Sweden (Swedish Democrats), Hungary (Fidesz), and France (National Rally).

These parties are enjoying success at the polls due to the crisis of confidence in the mainstream parties, whereby, it is felt that the current governments are not doing enough to counter the insecurities faced by citizens, such as the rising cost of living, high energy prices, law and crime, migration, etc. These parties have performed well not only in the opinion polls but have also won seats in national and regional elections, thereby, exercising influence in the government decision-making, whether they are a part of it or not. This article looks at the recent elections in four countries—Hungary (April 2022), France (June 2022), Sweden (September 2022), and Italy (September 2022)—to analyse the trends in the rise of the right-wing parties and key takeaways from this phenomenon.

A Look at the Elections

The elections in these countries were held against the backdrop of worries related to energy crises, the conflict in Ukraine, immigration, and law and order issues. Protests in countries such as Italy, France, Germany etc., against the rising cost of living have increased pressure on the political class to prioritise and find solutions to the problems faced by their citizens. The electoral breakthrough of right-wing parties represents the disenchantment of the general population with the mainstream political parties.

What appealed to the voters?

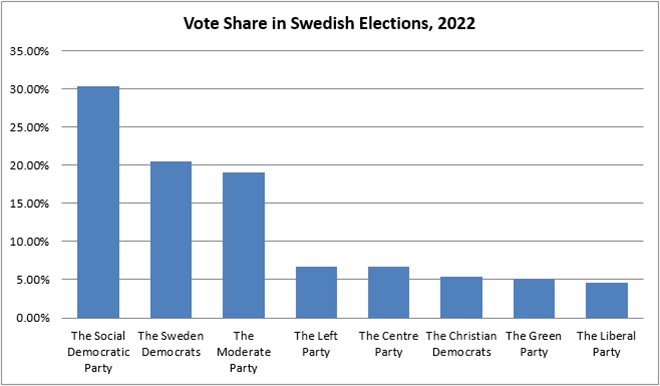

Despite the fact that right-wing parties are nationalistic and rooted in the issues and grievances that are usually country-specific, there are several concerns, such as anti-migrants’ attitude, unemployment, and viewpoints towards the European Union (EU), that are common to these parties across national boundaries. The Swedish Democrats, a party that is identified for its neo-Nazi roots, campaigned on immigration issues coupled with increasing gang-violence in the country, which they pegged with the deteriorating law and order situation due to high migration. High inflation, a looming energy crisis, and the conflict in Ukraine were also critical themes during the election campaign. Similar issues were also visible in the Italian elections.

Giorgia Meloni’s FdI traces its roots to the Italian Socialist Movement, a neo-fascist party formed in 1946 by supporters of Benito Mussolini. Her coalition partners include two veteran right-wing leaders, Mateo Salvini of The League and Silvio Berlusconi of Forza Italia. What worked in Meloni’s favour was that her party was the only one that chose to opt out of the unity government led by Mario Draghi, making it the sole opposition. This led the party to attract a majority of the protest votes. Moreover, Meloni, over the course of her campaign trail, moderated her party’s image as a supporter of the EU, Ukraine, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). Other critical issues included high cost of living, energy, immigration and economic opportunities for young Italians.

Some of these elements can also be traced in the steady performance of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France. Apart from moderating her party’s image, Le Pen had raised issues such as unemployment, protection of the welfare state, and raising minimum wage. President Macron’s tougher stand on immigration and law and order had also validated National Rally’s position on both the issues. In Hungary, President Orban’s hardline approach towards the working of the EU, immigration issues, his depiction of himself as “a defender of European Christendom against Muslim migrants, progressivism and the LGBTQ lobby”, and his idea of Hungarian neutrality in the Ukrainian conflict where he stated that, “this war is not our war”, were the key features of his campaign trail.

Vote Share

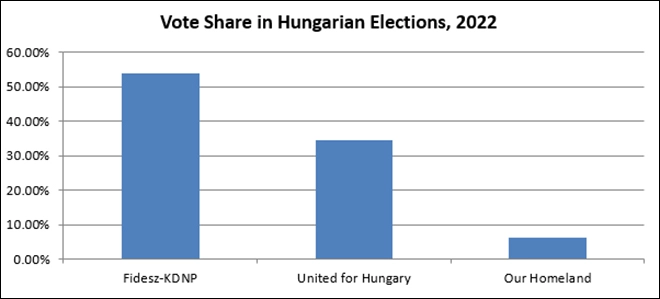

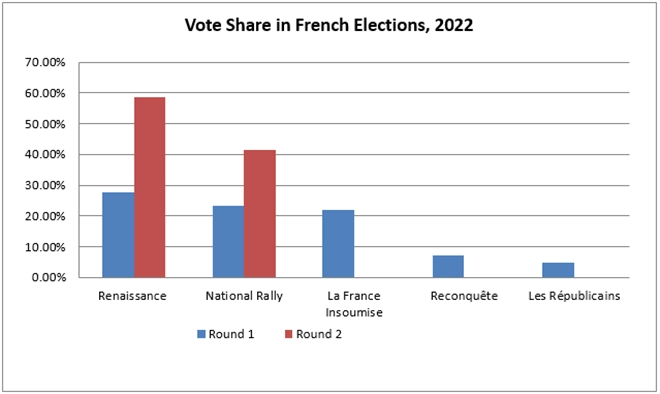

Hungary offers a successful example where a right-wing party, Fidesz, have been in power since 2010. Fidesz went on to win a supermajority in the April 2022 legislative elections with 53.7 percent of votes as compared to 49.2 percent in 2018. This was the highest vote share received by any party in Hungary since 1989. France is another example where a steady increase of vote share of the right-wing has been observed. The National Rally under Marine Le Pen has increased its vote share from 10 percent in 2007 to over 40 percent in the 2022 presidential elections. Under Le Pen’s leadership, the party has seen a steady progression to become one of two parties in the second round of last two presidential elections. While the party remains nationalist, anti-establishment, and anti-immigrant in its outlook, the rebranding under the current leadership has resulted in it moving away from xenophobic rhetoric.

In Sweden, the Swedish Democrats emerged as the second-largest party garnering 20.5 percent votes, increasing their share from 17.5 percent in the 2018 elections. Marking their strongest performance so far, the party emerged to be the kingmaker in the formation of the next coalition government. In Italy, FdI became the first far-right party to secure the highest vote share that any party had received in recent elections. The party increased its vote share to 26 percent as compared to 4 percent in 2018.

Voter turnout

The success of the right-wing parties is also influenced by voter disenchantment with the traditional parties, volatility of the political landscape, and general abstentions. The voter turnout in all the four elections witnessed a relative decline. In Hungary, the voter turnout was 62.92 percent in the 2022 elections as compared to 63.21 percent in 2018. In France, the voter turnout in the second round was 38.11 percent marking an abstention rate of 54 percent. The first round of these elections saw voter turnout of 47.5 percent, and abstention as 52.49 percent. In Sweden, voter turn-out has generally been high. However, this election witnessed a decline from 87.2 percent voting in 2018 to 84.2 percent. Similarly, in Italy, in the past few decades, the voter turnout has declined with 2022 elections witnessing 64 percent turnout as compared to 73 percent in 2018.

What does this mean for Europe?

It cannot be denied that right-wing parties have left a substantial footprint in the European political systems—some of the parties have become part of governments, others are leading opposition voices. These parties have let their presence felt by making mainstream parties take up their agenda and issues. The reason of the rise of right-wing politics is multi-faceted ranging from crisis of representation, growing personalisation of politics, increasing political and societal alienation, and dissatisfaction with the political system. The recent success of these parties is reflective of these sentiments.

A key takeaway is that these elections broke some key thresholds. In Italy, Giorgia Meloni became the first female prime minister with the most right-wing government since the Second World War. Italy’s government coalition consists of Meloni-led FdI, along with Matteo Salvini’s The League and Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. While this is not the first time a right-wing coalition is in government, however, it is the first time that a far-right party is at the helm of governance. Similarly, the Swedish Democrats, which has been treated as an outcast by the political establishment, emerged to be the second largest party in terms of vote share. While it has not become part of the coalition government, it has agreed to support the government from outside in what is called ‘supply and confidence agreement’ and is expected to have a substantial influence over key policymaking. The cordon sanitaire—that has prevented the far-right from taking office—appears to have been breached in these elections. Whether they are successful in running their coalition governments remains to be seen, but what is certain is that these coalitions will brings together leaders and parties that are fundamentally opposed to each other over many critical issues.

Another is their attitude towards working with the EU. Hungary, under President Orban’s leadership, has been at odds with the EU over issues like immigration, judicial reforms, and media freedom. The Commission has also initiated Article 7 infringement proceedings against the country. While the leaders of FdI, Swedish Democrats, and National Rally are no longer calling for withdrawal from the Union, they all have favoured devolution of power from Brussels to national capitals.

Within the EU, their outlook towards Russia will also be closely scrutinised, as some leaders have questioned the relevance of sanctions on Moscow. President Orban has played a critical role in using the veto to dilute several sanctions on Russia, especially the oil embargo, and has said that sanctions have a, ‘larger impact on European economies than their intended target.’ In Italy, while the FdI has declared its supportfor European efforts towards Ukraine, both Salvini and Berlusconi have appeared ambivalent in their opinions. The overall unity of the Italian government on the issue would depend on its internal dynamics.

Although these parties share some common themes, their behaviour once they come to power is determined both by the office they come to occupy, and the pulls and pushes of their coalition partners that contribute to the overall dynamics within the government. The parties may ideologically align but they include political figures with different views and priorities on issues including the EU, Ukraine-Russia, sanctions, economic policies, and immigration. While the party leaders may have been able to put aside differences during the campaign trail, they are likely to re-emerge as they work together as part of the government.