Understanding Indonesia’s 2024 Presidential Elections: A New Polarization Evolving – Analysis

By Max Lane

According to almost all recent polls, Indonesia’s Defence Minister Prabowo. Prabowo is the leading presidential candidate, scoring always over 40%[1] for “electability”. He has the support of the incumbent President, Joko Widodo, whose eldest son is Prabowo’s vice-presidential candidate and whose youngest son is chairperson of the fanatically pro-Prabowo Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI). Prabowo also has the support of former two-term president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, and prominent New Order military figure General Wiranto. There is also a kind of blessing from well-known members of the Suharto family, with Prabowo elevating his former wife, Titiek Suharto, to vice-chair of his party Gerindra’s Advisory Board.[2]

What is surprising is that despite all the support, his poll results less than a month out from the election on 14 February are considerably lower than those of candidate Widodo in the lead-up to the 2019 presidential election. At that time, Widodo was polling at over 50% with his opponent then, Prabowo, at 33%.[3] Today, even with Widodo’s and Yudhoyono’s ostensible support, Prabowo is scoring around 43%, up only 10% from 2019.

A NEW DIFFERENTIATION OR EVEN POLARISATION IN THE ELITE

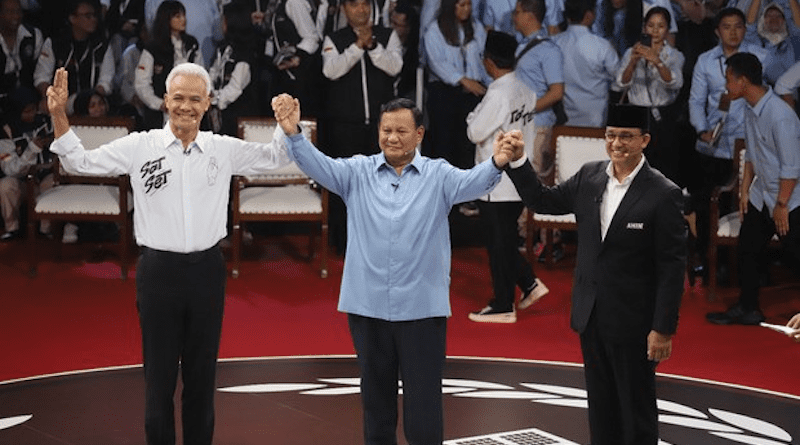

The 20-year period after the fall of President Abdurrahman Wahid has been characterised by the theatre of rhetorical polarisation among the Indonesian political elite. Although there is still some time left for campaigning, the contestation between the three presidential candidates – Baswedan, Prabowo and Pranowo – is revealing new cleavages which may reframe Indonesia’s political life. On the other hand, a consensus over the fundamentals of the status quo, as defined by government policies of the last ten years, may see a relapse into the politics of unanimity.

There are two types of political differentiation being revealed in the current electoral process.

The first relates to the nature of the coalition formed in support of Prabowo. As indicated above, this coalition comprises many elements associated with the New Order. Apart from Prabowo, Yudhoyono and Wiranto, there is also former Coordinating Minister Luhut Panjaitan, Widodo’s business partner since at least 2008.[4] Another is General Moeldoko, former Commander of the Armed Forces between 2013-2015, who Widodo appointed his Chief of Staff. Also appearing is long-term Golkar figure and oligarch, Aburizal Bakrie, the Mentor of Prabowo’s campaign team. While Widodo successfully portrayed himself in 2013-2014 as a novelty from outside the New Order elite, this image was belied by his immediate appointment of Luhut as a de facto ‘prime minister’, who was assigned more than 14 crucial policy implementation tasks.[5] This was followed later by Widodo’s rapid appointment of Moeldoko as his Chief of Staff and then his total rapprochement with Prabowo. Prabowo further indicated the process of Widodo’s integration into this milieu. His association with figures from Suharto’s New Order was further emphasised when Golkar recently posted an AI-generated video of the long-dead Suharto speaking for the Prabowo campaign.[6]

While there are also big business supporters of both the Anies Baswedan and Ganjar Pranowo candidatures,[7] this combination of ex-generals, Golkar figures and the Suharto family exposes Prabowo’s coalition as harking back to the Suharto era’s New Order. There is even talk of Prabowo and Titiek Suharto remarrying to bring a Suharto back into the presidential palace.[8] The Baswedan coalition and the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) both receive support from business figures who came into prominence during the New Order. Baswedan is supported by former Golkar figure and oligarch businessman, Surya Paloh. However, it can be argued that the latter supporters do not represent core New Order elements in the way that Prabowo’s coalition does.

The PDI-P itself, under the leadership of chairperson and former president Megawati Sukarnoputri, had opposed Suharto when he was moving towards a dynastic approach to politics. Suharto’s government intervened in the internal affairs of Megawati’s party to stop her from becoming its leader, and in 1998 Suharto appointed his daughter, Tutut, to the Cabinet in a clear attempt to pave the way for a dynastic succession.[9] For ten years, during the two presidential terms of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, the PDI-P was outside of government. The party is not based on or embedded in cronyism with the oligarchs at the level of national government. During the two terms of Widodo’s presidency, Widodo prioritised positions for his own cronies, especially Luhut Panjaitan but also others such as the academic, Pratikno. In the process, PDI-P has been kept out of the most important business-linked ministries.[10]

Baswedan, as a politician and an academic prior to that, has not been embedded in any party or other institution. He courted the Democrat Party (PD) in 2013, then the PDI-P during Widodo’s 2014 campaign, and was nominated by the Justice and Welfare Party (PKS) and Gerindra when he stood for Governor of Jakarta in 2017, prior to being supported by the National Democratic Party (Nasdem) and the National Awakening Party (PKB), as well as the PKS for his presidential campaign now. This is the history of an ambitious politician, but one not embedded within the core of the elite coming out of the New Order.

This new polarisation between core New Order elite elements, now including Joko Widodo, and those outside has meant that the polarisation is creating concern beyond the political parties, among some elements of civil society. This is most visible in sections of the media – led by the liberal TEMPO magazine[11] – as well as human rights NGOs and students opposing the Prabowo-Gibran Rakabuming Raka (read: Widodo) camp. There are two reasons for these concerns. First is the use of Widodo’s incumbency to build a dynasty for his family, and second is the displayed impunity (Prabowo’s) for past human rights violations. The liberal media has led in expressing these worries, but in early January 2024, the first signs appeared of what may well become a student protest movement.[12]

This polarisation also envelopes the political parties. The Widodo-Prabowo camp has alienated the key party outside the New Order core, the PDI-P. Widodo and Prabowo owe their access to the national political stage to Megawati and her PDI-P.[13] For 2024, however, they have united to defeat the PDI-P’s candidate, Ganjar Pranowo. In Widodo’s case, the betrayal may be seen to have begun with the rapprochement with Prabowo in 2019, although Widodo kept up a semblance of loyalty to the PDI-P until 2023. The alienation from the PDI-P was underlined by Widodo’s absence at the party’s recent 51st anniversary celebrations while other major figures such as Vice-President Ma’ruf Amin, Finance Minister Sri Mulyani as well as Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (“Ahok”), now a member of the PDI-P, were in attendance. At this event, Megawati referred to all the ministers who attended as “those willing to attend”, an obvious implied sneer at Widodo who arranged to be overseas at this time.[14]

The alienation of the PDI-P by and from Prabowo and Widodo now aligns that party with the media and some civil society elements whose primary orientation is “Asal Bukan Prabowo” (Anybody but Prabowo) – a theme often reported as “trending”.[15] It should be noted that there are significant civil society elements who are not supporting any of the three presidential candidates. Even so, that alignment adds to the dynamic of polarisation.

The position of the Anies Baswedan campaign in this new polarisation is also clear, although its origins are different. Baswedan is now solidly situated as key to the opposition against Prabowo. Unravelling the nature of the oppositional relationship requires also considering the political culture of the New Order core. The basis for an alliance between the three parties – Nasdem, PKB and the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) – may seem to be primarily opportunistic, although all three can claim to be outside of the New Order core. While Surya Paloh was a significant figure in Golkar in the last years of the New Order, his small Nasdem party has kept itself at arm’s length from the New Order elements. A prominent spokesperson for Nasdem in the current campaign is Surya Tjandra, who is historically associated with civil society criticism of the New Order. Tjandra was a human rights lawyer close to the trade unions until he joined the Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI) in 2018, when it was still perceived as a party with a democratic ideology. He became a deputy minister (agrarian affairs and spatial planning) in Widodo’s Cabinet. Now, in Nasdem, he is campaigning for Baswedan as a candidate who can propound development and ideology against a purportedly hapless Prabowo on that score.[16]

Both through the televised presidential debates (12 December 2023 and 7 January 2024; 4 February forthcoming) as well as general campaigning, Baswedan presents himself as a candidate with deep ideas and who can explain the concepts involved. He is considered a technocratic intellectual. Symbolic of this approach, although not the only example of it, is Baswedan’s proposals for alternatives to a new national capital in Kalimantan, the latter being depicted as a glamour project, and at the same time pushing his team’s proposal for developing 40 other cities throughout Indonesia to a higher level.[17]

However, it is not so much the content of Baswedan’s policies that differentiates him from the Prabowo campaign but the very notion of a serious policy discussion. This contrasts totally with Prabowo’s strategy of creating a new image for himself as the “adorable grandpa” who can joget (dance), and spreading the message that politics should be “fun”.[18] His campaign has flooded social media with animations of the “adorable grandpa” in the form of a dancing Prabowo.[19] Running a election campaign as entertainment can be said to contain an element of “Jokowism”. Candidate Jokowi would use political rallies to entertain the crowd with quizzes, with prizes being given out to audience members who could answer simple questions.

Another key aspect of Baswedan’s campaign are the “desak Anies” (“Press Anies”) meetings where constituents are invited to press (question) Baswedan on any issue, face to face. This seems particularly popular among young people;[20] the sessions can be watched live on YouTube[21] and some excerpts can be viewed on TikTok.

This aspect of the polarisation – a technocratic vision for managing Indonesia versus the personalised character of Jokowi-ism and Prabowoism – came across in the third (second for the presidential aspirants) round of the televised debates on 7 January. Baswedan and Ganjar Pranowo critically questioned Prabowo on his implementation of policies as minister of defence, to which the latter reacted defensively.[22] Prabowo seemed not to be armed with the data needed to defend himself, lamenting afterward that he did not expect to be quizzed in this way. Almost ten years of rhetorical polarisation rather than real polarisation means he was equipped only with rhetoric, expressed sometimes with somewhat uncontrolled emotions.[23]

On 7 January, Baswedan tested Prabowo on issues underlying this polarisation, especially in relation to Widodo’s political dynasty-building. In an exchange on ethics, Baswedan asked Prabowo whether it was ethical for him to continue with his current vice-presidential running mate even after the Constitutional court process which cleared the way for Gibran to be nominated was judged to be ethically flawed. Prabowo reacted defensively and emotionally, declaring that Baswedan did not have the moral authority to talk about ethics.[24]

Baswedan also raised issues aimed at depicting Prabowo as being guilty of New Order style wrongdoing, including his alleged accumulation of 340,000 hectares of land – a figure disputed by Prabowo – and procurement of military equipment “using middle-men”, implying possible corruption.[25] This latter issue had been reported by TEMPOnewsmagazine.[26]

Almost all polling following this debate rated Baswedan and Ganjar much higher that Prabowo in terms of performance.[27] Ganjar had clearly prepared himself to be technically well-informed, and his confident and combative interrogation of Prabowo saw some polls rating him the winner.[28] The debate went some ways towards contouring the differentiation between the candidates.

HOW WIDE IS THE NEW POLARISATION?

The 2014 and 2019 elections were marked by rhetorical rather than real polarisations.[29] The current polarisation is different in that it has a base in the legacy of the 32 years of the New Order, with its mode of governance built around dynastic power, cronyism, and a right to rule presumed by members of the New Order elite. This legacy is also characterised by the division between those integrated into that culture or hankering to be a part of it, and those excluded from it. Over time, the latter, as the consequence of different personal/political histories, have attained starkly different political outlooks.

Be that as it may, this new polarisation does not reflect fundamental variances based on basic economic or social divides. Rather it is a differentiation around mode of governance. Should governance be subordinated to personal ambition and dynasty-building or to the technocratic management of society and of its economic growth?

While this appears to be a genuine differentiation, it is important to note two factors. First, this differentiation is still in an early stage. Second, it is not yet clear to what extent this differentiation is important to the political players involved – especially the parties supporting Baswedan and Ganjar. It is no doubt a differentiation closely connected to Baswedan’s academic/intellectual background and ideology, but the dynamics go beyond that. Even the PDI-P, together with the smaller political parties, will benefit from a more regulated form of governance, where the personal wealth of political players and their oligarchical connections, are a lesser determinant of electoral success.

At the same time, the strength of commitment to a modern, technocratic management of society and economic growth among all the major parties – the PDI-P, the United Development Party (PPP), Nasdem, PKB and PKS – is still untested.

Unlike the rhetorical polarisations of 2014 and 2019, this new polarisation so farappears to be primarily confined to and visible within the political elite. This elite is defined here as going beyond political parties to include to a significant extent the mainstream media, civil society and its social media. To what extent these differences are being discussed or being perceived as important among Indonesia’s 204 million voters[30] is still unknown. Prabowo was scoring 43-46 per cent for his electability in December 2023 – early January 2024 in polls, but according to survey firm Indikator Politik Indonesia, his numbers possibly stagnated thereafter.[31]

It is worth noting, however, that some polls are recording high numbers for undecided voters. A Kompas poll recorded 28.7 per cent of respondents as being undecided in early December 2023.[32] Another poll on party support for the legislative elections (also on 14 February) noted a 5.9 per cent increase in undecided voters from August 2023, up to 17.3 per cent.[33] There are no polls yet that show what the conscious abstainer or spoiled vote (called golput in Bahasa) might total.[34] The reported stagnating of support for Prabowo in more recent poll results raises questions over what is going on in the minds of voters.

As of 24 January, there are limited signs of the Baswedan and Pranowo campaigns coordinating their efforts, with this scenario being discussed by former vice president Jusuf Kalla, who supports Baswedan.[35] Their immediate aim would be to ensure that Prabowo’s level of support does not exceed the crucial level of 50 per cent, thus ensuring a run-off second round in late June 2024. It is possible that the two coalitions will work together to increase the vote for their individual parties by directing their supporters to vote for each other’s parties in some districts.[36] Baswedan’s running mate, PKB chairperson Muhaimin Iskandar, in his formal greeting at the PDI-P’s 51st anniversary celebration, spoke positively about cooperating with PDI-P, including in a run-off.[37]

The novelty of the current differentiation makes it harder to predict an outcome for the elections. The assumption that Prabowo, with the support of the incumbent Widodo, was assured of a clear win is now being questioned. Has Prabowo’s support stagnated or will some unforeseen element revitalise it? Or has support for him peaked, and will henceforth move downwards?

- About the author: Max Lane is Visiting Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. He is the author of “An Introduction to the Politics of the Indonesian Union Movement” (ISEAS 2019) and the editor of “Continuity and Change after Indonesia’s Reforms: Contributions to an Ongoing Assessment” (ISEAS 2019). His newest book is “Indonesia Out of Exile: How Pramoedya’s Buru Quartet Killed a Dictatorship” (Penguin Random House, 2022).

- Source: This article was published at ISEAS Perspective

- Endnotes: For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.