The United States’ Afghanistan Policy – OpEd

By Mumtaz Ahmad Shah and Syed Asrat*

Afghanistan is a landlocked country in south-central Asia. Its modern borders are the product of the Great Game of Central Asia. The British interests decline in Afghanistan with its withdrawal from the Indian Subcontinent. However, the successor of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, developed strong interests in Afghanistan. Its strategy was to support the transformation of Afghanistan into a secular and nationalist state for its own domestic interest of keeping Central Asian Muslims under control. The imposing of economic and social change to a conservative society backlashed in the form of civil war. The failure of Afghanistan’s communist regime resulted in the Soviet Union made a direct military intervention in December 1979. The US grand strategy for the Cold War was set to contain communism and the Soviet Union. The Carter Administration joined hands with Pakistan and backed the resistance front inside Afghanistan. The Mujahedeen forces withstood against the Soviet occupation, and on the diplomatic table, the Americans dictated the collapsing Soviet Union. By 1989, the Soviet army withdrew from Afghanistan, and we witnessed a decline in the US interest in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

In 1990, the Soviet Union was a step away from disintegration, the Kuwait crisis erupted. The post-Cold War world was witnessing a unipolar momentum. The US national power was unlikely to be balanced by any combination of the next ten military powers. The neoconservative dominated the discourse on the post-Cold War grand strategy. Neoconservatives were advocating the promotion of democracy and interventionism in international affairs and peace through strength. When the US mobilized the international community against Iraq’s occupation of Kuwait in 1990, the neoconservatives within the Bush administration advocated greater US activism in the region. They project West Asia a dividing gap that either failed to integrate into the US-centric world order or challenged the US interests by not making peace with Israel. The US Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney flew to Jeddah to persuade the Saudi king to accept American troops to defend the kingdom. The US-led coalition of thirty-nine nations invaded Iraq. For the first time in the region’s history, the invading forces were much larger than the entire armies of the Gulf region. Through this act, the US warned the Arab world that the territorial status quo was a permanent future. The US had come to the Gulf region not only to defend the pro-West secular monarchies but had larger goals to contain Iraq, Iran, and Islamists. Ostensibly, by mid-1992, the Bush administration had established two open-ended no-fly zones over Iraqi territory, one in the north and another in the south.

The US Congress passed the Jerusalem Embassy Act of 1995. The US Congress introduced the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act in 1996. Through the United Nations Security Council Resolution 661 and Resolution 687, Iraq was pressured to disclose and eliminate its weapons of mass destruction (WPD). Clinton Administration passed the Iraq Liberation Act in 1998. The neo-cons like Cheney, Donal Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz, and Scooter Libby had signed on to the Project for the New American Century in 1998 to propagate the information in favor of “regime change in Iraq.”

Surprisingly, the balancing tendency against the US hegemonic behavior came from Al Qaeda, the non-state actor, which has origin in the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. The Al Qaida leader, Osama Bind Laden, saw the Christian Crusade as a continuous process against Islam. He treated the US’s unconditional support to Israel, deployed US troops to Saudi Arabia, and forced Iraqi people to suffer under sanctions as interconnected developments. The unfolding of post-Cold War politics was defined by Bernard Lewis in 1990 and Samuel Huntington in 1993 as coming back to the old fault-lines of the clash of civilizations.

The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, Aden, Mogadishu, the National Guard Training Center, Riyadh, and the Khobar Towers rationalized the US military presence in West Asia. However, Osama Bind Laden’s shift from Sudan to Afghan complicated the US objectives. The Saudi regime requested the Taliban government to host Osama; not the Taliban had invited him. From the caves of Tora Borah, Laden was giving interviews to the western media. Bin Laden, in 1997, in an interview, said, “the US is ‘unjust, criminal and tyrannical power. It wants to occupy our countries, steal our resources, and impose on us agents to rule us.”

With American attention focused on Afghanistan, Mullah Omar and the Taliban government came under the international scanner. President Bill Clinton planned Operation Infinite Reach. It launched thirteen Tomahawk cruise missiles on a suspected al-Qaeda chemical weapons site in Sudan and sixty-six cruise missiles launched on bin Laden’s two camps around Khost in Afghanistan. After the US strikes, the Saudi intelligence director Prince Turki and ISI director General Naseem Rana arrived in Kabul together Kabul and demand bin Laden. Mullah Omar dug in his heels and spat defiance at Turki: bin Laden was a “man of honor. Instead of seeking to persecute him, you should put your hand in ours and his and fight against the infidels.

Meanwhile, in the US, there was a change of government in 2000. In a two-hour meeting with George Bush Jr., the outgoing president Clinton told the incoming president that “by far your biggest threat is bin Laden and the al-Qaeda.” At the same time, the neoconservative had made no secret of their contempt for the Oslo Accords and Clinton’s interventions in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. They wanted to restore the US strategic focus on West Asia, particularly Iraq, Iran, Hezbollah, and Hamas.

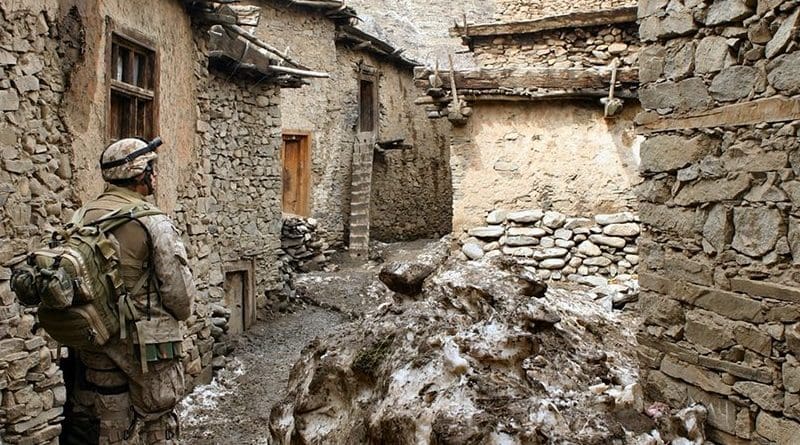

The Al Qaida attacks on the US homeland in 2001 dragged the US into Afghanistan. The neo-cons and other voices were not in favor of the greater role of the US beyond eliminating terrorist networks. Senator Tom Daschle and Cofer Black of the CIA expressed their reservations and suggested President Bush tread Afghanistan softly. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld stressed that America would provide air support to indigenous troops. George Tenet and Cofer Black warn Bush and Cheney that “the war would be driven by intelligence, not the pure projection of power. The challenge wasn’t to defeat the enemy militarily. The challenge was to find the enemy.”

The Taliban stalled for ten days and then announced that they would not hand bin Laden over to the US. On October 7, 2001, Bush launched Operation Infinite Justice to kill off the Taliban, flush out the Arab Afghans, and capture or kill Osama bin Laden. In the aftermath of the 2001 Bonn Agreement and the formation of a new cabinet under Hamid Karzai, much of the administration came from Northern Alliance, geographically representing non-Pashtun ethnic groups of northern Afghanistan and ideologically influenced by Pakistan’s Jamat-i-Islami and the Muslim Brotherhood. Very soon, President Bush dispatched Zalmay Khalilzad as his special envoy to Afghanistan. Secretary of State Colin Powell, on a visit to Islamabad, was induced by his Pakistani hosts to hold out an olive branch to moderate elements in the Taliban. Rumsfeld persuaded Bush fighting al-Qaeda inside Afghanistan would not solve the challenge of emerging “nexus of terrorism and weapons of mass destruction.” Although there was no link between al-Qaeda and Iraq or concrete proof that Saddam Hussein was making nuclear weapons, the neo-cons were preparing the ground for the US invasion of Iraq. Bush’s treasury secretary, Paul O’Neill, recalled that at President Bush’s first National Security Council meeting in January 2001, finding a reason for a war to remove Saddam Hussein had been the principal order of business. By November 2001, the administration had already made up its mind to invade Iraq. The Bush Doctrine was published in September 2002, held that Washington would use its peerless military power to topple totalitarian regimes that menaced the US, pre-empt terrorist attacks and spread democracy. The Bush Doctrine was precisely what neo-conservatives had been seeking ever since the Soviet collapse. In his State of Union address of 2002, American President Bush used the theological language that the civilized world faces unprecedented dangers from ‘Axes of Evil’ composing of Iraq, Iran, and North Korea (Bush 2002). Iraq’s refusal to let the United Nations Special Commission back into the country gave Bush a useful lever to accuse Saddam of hiding a formidable WMD program. The confluence of Saddam’s defiance of UN Security Council resolutions became the justification for waging war in Iraq in 2003.

Thus, the US actual military interest was the Gulf region of West Asia, and amid of Afghanistan war, it opened the Iraq front. This explains why the US pursued diplomacy with the Taliban. There were also limits to the ruling Afghanistan regime building a stable and democratic state because the Taliban is a combination of political Islam and Pastunwala nationalism. Next, the US priority shifted to the Indo-Pacific region. This development unfolded in the backdrop of the Euro-Atlantic financial crisis of 2008. China has found opportunities to lead the global international market by setting norms and new institutions. China is the third great power after Great Britain and the US, which can shape the world order. Realizing the altering balance of power in world politics, President Obama came with the strategy of Asia Pivot. The Asia-Pacific is the region wherein China’s power projection has a natural inclination, and the same is the area where Beijing is vulnerable, as its major trade and energy lanes of communication go by the South China Sea. At the behest of the Obama administration, Qatar opened the Doha peace process in 2013. President Donal Trump normalized diplomatic contacts with the Taliban and declared ending the Afghanistan war his priority. The US has declared China, Russia, and Iran as revisionist powers, while the US has limited power projection capabilities in the continental domain. So the changed great power politics does not favor the US presence in Afghanistan. The US has set the September 2021 final date for ending its two decades of military occupation of Afghanistan. The minimum assurance that the US demands from the Taliban is that Afghanistan should not become a safe haven for terrorist networks that can attack the American homeland.

As such, why the Taliban-America peace process progressed is explained by where the US strategic focus was. The US strategic priority in the post-Cold War period was West Asia, not Afghanistan. In the post-America period, the US is facing China, which is unlike the Soviet Union, is not only formidable military power but also is a global economic and technology powerhouse. The extra-regional power always has an option to withdraw from the war scene, so is the US doing. Afghanistan’s challenge is twofold: one breaking the intra-Afghanistan peace process that represents multi-ethnic harmony of Afghan society, and second deny regional powers maneuverability, which can bring back the ghost of ethnic war.

*Mumtaz Ahmad holds Ph.D. in International Relations. He can be reached at [email protected]