The 1988 Iranian Prison Massacre – Analysis

By Hamid Enayat and Middle East Quarterly

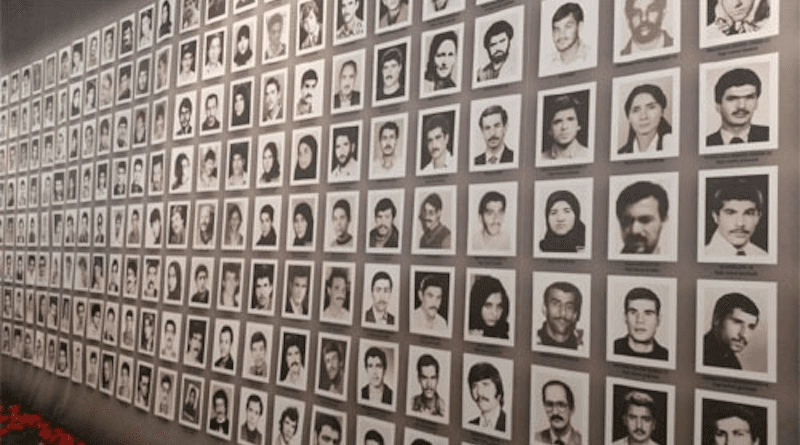

A much ignored yet gruesome massacre in Iran’s prisons in 1988 has come to light following three unrelated events. The first is the ascent to the country’s presidency, if not to actual power, of Ebrahim Raisi, a former chief justice, who headed one of the country’s biggest financial trusts (Astan-e-Ghods) for years while maintaining links to the judiciary.

In 1988, Raisi sat as deputy prosecutor general in a 4-member committee codenamed the “death commission” which was charged with purging the Tehran and Karaj (a city close to Tehran) prisons of political prisoners still loyal to the banned opposition People’s Mujahideen Organization of Iran (the Mujahideen-e Khalq or MEK). Several thousand prisoners already condemned and serving time were thus re-examined, and the majority of them were then executed in a matter of months on orders issued by Raisi and his three colleagues.

The second event is the arrest and trial of “Hamid Noury” in Stockholm’s Arlanda airport in October 2019 as he sought to enter Sweden as a tourist. Noury was actually Hamid Abbasi, a notorious prison official who played a pivotal role in Karaj’s Gohardasht prison in the summer of 1988 in tandem with the death commission in which Raisi had an important role. Some forty former political prisoners who survived the massacre are plaintiffs in Noury’s trial, which began in September 2021. On July 14, 2022, the court condemned Noury to life imprisonment, a verdict that Noury appealed, and the appeals’ hearings, which began on January 11, 2023, are now ongoing. Noury is the first Iranian official to be tried according to the international jurisdiction on war crimes.

The third event involves the alleged role of Iran’s then-ambassador to the United Nations, Mohammed Jafar Mahallati, in covering up evidence of the mass killings in 1988. An Amnesty International report condemned Mahallati’s actions at that time. According to the report, Mahallati

undertook efforts in late November and early December 1988 to block the adoption of a resolution by the U.N. General Assembly that expressed concern about the mass executions … [and] misrepresented the executions as battlefield killings.[1]

And article in the Oberlin Review reported,

In 1989, Mahallati wrote a letter from the Permanent Mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the U.N. in New York claiming the individuals killed had “direct organizational contacts with … a treacherous espionage network.”[2]

Mahallati is now a tenured professor of religion at Oberlin College. Family members of people killed during the 1988 massacres are currently engaged in a public campaign to have him removed from his academic position in the United States

Who Are the MEK?

The People’s Mujahedeen Organization of Iran (MEK) represents a strain of political and religious thinking wholly distinct in substance and in many forms and customs from the religious interpretations and functioning of the ruling system in Iran. The MEK advocates for the equality of women and men in all political, social, and economic aspects. Equality of women and men is something that the Khomeinist clerical establishment does not accept. In Iran today, the legal code is based on women being half the human beings that men are.

Regarding the involvement of religion in government, the MEK believes in the principle of separation of religion from state. It codified this in its “yes” vote to the principle as approved by the National Council of Resistance of Iran. This is an absolute heresy for the ruling theocracy.

From the first day of his rule, Khomeini tried to draw the MEK away from its beliefs and force it to bend to his religious leadership and authority (velayat-e faqih). As it became clear that this was not feasible, he chose to destroy the MEK, first, politically and then to exterminate them physically. In April 1980, Khomeini told a private meeting in Qom with several close clerics:

Islam minus the mullahs is what they say … is the Mujahedeen’s position, and the clergy must settle their account with them.[3]

So, what exactly happened in the summer of 1988 in Iran’s prison system?

The Indictment

The Swedish court prosecutor’s indictment against Hamid Noury reads:

Khomeini [the supreme leader of the Iranian regime 1979-89] issued a fatwa or decree [in the summer of 1988], stating that all prisoners in Iranian prisons who were affiliated with or supporters of the MEK, and who were faithful in their beliefs, were to be executed. Shortly thereafter, mass executions of supporters and sympathizers of the MEK who were imprisoned in Iran’s prisons began. … Documents registered with the Swedish Prosecutor Authority and existing in the case file include the list of 444 MEK prisoners who were hanged in Gohardasht prison alone, a book entitled “Crimes against Humanity” with the names of more than 5,000 MEK members, a book entitled “Massacre of Political Prisoners” that was published by the MEK 22 years ago, which includes a list of a considerable number of agents and perpetrators of the massacre, including Hamid Abbasi (Noury), in addition to the memoirs of a number of MEK members and sympathizers.[4]

Helpless and frustrated by a growing wave of protests, especially among women, girls, and the younger generation, in the summer of 1988, Khomeini issued a fatwa ordering the killing of political prisoners, mainly from the MEK. The fatwa, written in Khomeini’s own handwriting but without a date, was carried out by Khomeini’s religious judges, including Iran’s current president, Ebrahim Raisi.

The victims had stood up to Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, and challenged the theory of velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurisprudent)—the ruling ideology of the Islamic Republic. Khomeini’s fatwa led to the killing of thousands of political prisoners, primarily supporters and members of the MEK. Only after forty years, thousands of testimonies, and the revelation of hundreds of documents did a part of the international community become aware of this horrific crime. At Hamid Noury’s trial in Sweden, Mahmoud Royaie,[5] one of the former prisoners who survived the massacre in the summer of 1988, said the massacre had been planned much earlier by the regime.

Fatwa for Murder

This logically precedes the Swedish document. The most important document legitimizing the massacre is a fatwa, a religious ruling, by then-supreme leader of the Islamic Republic, Ruhollah Khomeini, written in his handwriting. It reads as follows:

As the treacherous Monafeqin [Mojahedin] do not believe in Islam and what they say is out of deception and hypocrisy, and as their leaders have confessed that they have become renegades, and as they are waging war on God, and as they are engaging in classical warfare in the western, northern, and the southern fronts, and as they are collaborating with the Baathist Party of Iraq and spying for Saddam against our Muslim nation, and as they are tied to the World Arrogance [a phrase referring to the United States-Ed.]. In light of their cowardly blows to the Islamic Republic since its inception, it is decreed that those who are in prisons throughout the country and remain steadfast in their support for the Monafeqin [Mojahedin], are waging war on God and are condemned to execution.

It is naive to show mercy to those who wage war on God. The decisive way in which Islam treats the enemies of God is among the unquestionable tenets of the Islamic regime. I hope that with your revolutionary rage and vengeance toward the enemies of Islam, you will achieve the satisfaction of the Almighty God. Those making the decisions must not hesitate, show any doubt, or be concerned with details. They must try to be most ferocious against infidels. To have doubts about the judicial matters of revolutionary Islam is to ignore the pure blood of martyrs.[6]

A 1990 Le Monde article reports:

Imam Khomeini summoned the revolutionary prosecutor, Hojjato-Islam Khoeiniha, to order him to have all the Mujahideen [MEK members] executed, whether in prison or elsewhere, for going to war with God. The executions followed summary trials. The trial consisted of using different pressure methods to force the prisoners to repent, change their opinion or confess. Among the very young Mujahedin executed were some of those who were imprisoned for eight years, when they were only 12 to 14 years old, for having taken part in public demonstrations.[7]

“We Will Be Condemned by History”

Among Iranian officials, only Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri, the intended successor to Khomeini, objected to the killing following Khomeini’s fatwa. He stated his concerns:

How can a prisoner who has been sentenced and is serving his sentence be hanged? What should be the answer to families who come to visit their children in the prisons? How can we respond to history when a prisoner cannot be retried and executed under any international law?[8]

Khomeini was angered by Montazeri’s remarks. As a result, he dismissed Montazeri as his successor, and the latter spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

In August of 2016, Montazeri’s son released an audiotape from Ayatollah Montazeri denouncing the massacre. In the 40-minute tape, recorded during a closed-door meeting between Montazeri and four members of the Death Committee on August 15, 1988, Montazeri charged the attendees with conducting the “purge” of Iranian prisons. Montazeri protested the terrible killing that had begun a few weeks earlier and its magnitude and added:

The most horrific crime committed under the Islamic Republic and for which we will be condemned by history, you are the ones who committed it, and that is why history will record your names as criminals … Ahmad Khomeini [Khomeini’s son] has been saying for 3-4 years that the PMOI [MEK] activists should all be executed, even if those people have only read their newspapers, their publications. Girls as young as 15 and pregnant women are among the victims. However, in Shiite jurisprudence, even if a woman is “Mohareb” [at war with God], she should not be executed. This is what I told Khomeini, but he replied, “No, execute the women, too.”[9]

Montazeri continued:

In this way, it becomes clear that Ahmad Khomeini, who was closest to Khomeini and was his right-hand man, had been saying for several years that all Mujahideen and anyone with whom they had any connection, even if they had read their newspaper, should be killed.[10]

The dimensions of the regime’s intended massacre can be estimated based on the circulation of the MEK publications, which was more than half a million copies before its printing facilities were confiscated, destroyed, and closed. Montazeri’s statement leaves no doubt that Ahmad Khomeini, who was very close to his father, was instrumental and influential in the killing of members and supporters of the MEK, even if the charge against them was only the reading of an MEK newspaper.

Following the 2016 release of the Montazeri audiotape, the MEK massacre became public knowledge for the first time. The Iranian authorities had always sought to suppress this bloody episode, fearing prosecution before an international criminal court for what Amnesty International has described as a “crime against humanity that has gone unpunished.”

Additional Evidence‘

In addition to Khomeini’s fatwa, another document in his handwriting and bearing his signature reveals his determination to kill MEK members and supporters. The document is a short text written in response to his son Ahmed’s questions. Fearing the social effects of this sentence and its repercussions inside and outside Iran, some city judges had raised questions and ambiguities about implementing Khomeini’s fatwa. They sent their questions to the head of Khomeini’s court, Moussavi Ardebili. Moussavi feared writing directly to Khomeini to ask him about it. Instead, he asked Ahmad Khomeini to ask his father these questions in writing. Ahmed’s letter to his father reads:

My Pre-eminent Father, His Eminence the Imam,

With greetings, [Chief justice] Ayatollah Moussavi Ardebili has telephoned to raise three ambiguities about Your Eminence’s recent decree on the Monafeqin [Mojahedin]:

1. Does the decree apply to those who have been in prison, who have already been tried and sentenced to death but have not changed their stance, and the verdict has not yet been carried out, or are those who have not yet been tried also condemned to death?

2. Those Monafeqin [Mojahedin] prisoners who have received limited jail terms and who have already served part of their terms, but continue to hold fast to their stance in support of the Monafeqin [Mojahedin], are they also condemned to death?

3. In reviewing the status of the Monafeqin [Mojahedin] prisoners, is it necessary to refer the cases of Monafeqin [Mojahedin] prisoners in counties that have an independent judicial organ to the provincial center, or can the county’s judicial authorities act autonomously?

Your son,

Ahmad

Khomeini’s reply:

In the name of God, the Highest,

In all the above cases, if the person at any stage or at any time maintains his [or her] support for the Monafeqin [Mojahedin], the sentence is execution. Annihilate the enemies of Islam immediately. As regards the cases, use whichever criterion speeds up the implementation of the verdict.

Ruhollah Moussavi Khomeini.[11]

In a speech to an international online conference in the presence of more than a thousand Iranian former political prisoners, Eric David, an internationally recognized expert on international humanitarian law, declared:

It is obvious that the crime committed in 1988 against the 30,000 members of the People’s Mujahedin Organization of Iran is clearly a crime against humanity… for religious reasons, for belonging to a religion, these people were massacred, they were considered as apostates, so it corresponds perfectly to the definition of Article 2 of the 1948 Convention on genocide. So, there is no doubt that these facts are indeed facts of genocide, even if the word genocide is sometimes used in a slightly excessive way, the fact remains that in this particular case, the massacres of 1988 can legally be qualified as genocide.[12]

Culture of Impunity

Although the massacre became known in 1988 and the U.N. General Assembly condemned the extrajudicial executions in December 1988, the reaction to the massacre never reached significant dimensions. The full extent of the crime was not known at that time. Still, the inaction by international actors was surprising. A culture of impunity existed in Iran, which continues to this day.

In September 2020, an official letter from a group of 150 U.N. experts—including former U.N. High Commissioner on Human Rights and former Irish president Mary Robinson, and Mark Malloch-Brown, former U.N. Deputy Secretary-general—sent to the government of Iran and later published as an official U.N. document on the affair, reads as follows:

To date, no official in Iran has been brought to justice and many officials involved continue to hold positions of power including in key judicial, prosecutorial and government bodies responsible for ensuring the victims receive justice. … There is a systemic impunity enjoyed by those who ordered and carried out the extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances.

The U.N. experts concluded:

Although the U.N. condemned the executions in 1988, the inaction by international actors was surprising.

The situation was not referred to the Security Council, the UNGA did not follow up … and the UN Commission on Human Rights did not take any action. The failure of these bodies to act had a devastating impact on the survivors and families as well as on the general situation of human rights in Iran and emboldened Iran to continue to conceal the fate of the victims and to maintain a strategy of deflection and denial that continue to date.[13]

In a report published in 2017, Amnesty International wrote:

Former prisoners from Evin and Gohardhasht prisons refer to a pattern of threats, interrogations, classification procedures, and transfers of prisoners between Evin, Gohardasht, and other prisons in the months leading up to July 1988, well before the MEK’s armed incursion on July 25. In hindsight, many are certain this was a prelude to the mass killing of the prisoners.[14]

Amnesty International‘s research revealed a similar pattern in various provincial prisons. Survivors from these prisons told the organization that prisoners faced unexpected interrogations between late 1987 and mid-July 1988, either orally or through extensive written questionnaires, which focused on their political opinions and continued commitment to opposition groups. Survivors also reported that, during the same period, prison officials and interrogators threatened that, at some point, “they would be ‘dealt with’ and that the prisons would be ‘cleansed.'”[15]

Another pattern that some survivors believe indicates the pre-planned nature of the killings was the massive wave of arrests of hundreds of prisoners, who had been released several years earlier, during the weeks leading up to July 1988 and shortly after the MEK armed incursion on July 25, 1988.

Amnesty International‘s research also points to a nationwide pattern of transferring prisoners unexpectedly and without explanation from their home city to elsewhere, sometimes far from their own provinces, in the months preceding July 1988. Many former prisoners believe these transfers were part of a separation exercise aimed at identifying prisoners who were “steadfast” in their political beliefs and marking them for continued imprisonment and possible elimination.[16]

The prisoners also said that the transfers enabled the authorities to restrict the flow of information during the mass killings in small towns and cities where there was a greater likelihood of families knowing judicial officials and prison guards through local networks and extended families.”

“A Wound That Remains Open”

The 2017 Amnesty International report reveals the subsequent deliberate desecration and destruction of several mass graves where the 1988 massacre victims are buried. Documents, including satellite photos, support the evidence of the attempted demolition of these and other mass graves. New buildings and roads with no apparent use have been built over these mass graves.

The report estimates that more than 120 locations across the country contain the remains of victims of the 1988 massacre. It identifies seven sites where destruction of the burial sites has been confirmed or suspected between 2003 and 2017.[17] Large cities like Mashhad have several mass graves. Construction work has begun on the mass gravesites on each of these sites. Satellite images sometimes show very rapid progress on the work.

Testimonies show that in 1988, families of the victims were informed by the authorities that their relatives had been executed without any additional information regarding the circumstances of their death and their burial place. In addition, the families were forbidden to organize memorial gatherings or decorate the graves with flowers and messages in memory of the deceased. Some victims’ relatives have also been prosecuted, imprisoned, and tortured simply for seeking truth and justice.[18] According to Philip Luther, director for the Middle East and North Africa at Amnesty International:

The atrocities of the 1988 massacre in Iran are a wound that remains open three decades later. By destroying this vital forensic evidence, the Iranian authorities are deliberately reinforcing an environment of impunity.[19]

Unpunished Genocide

British lawyer Geoffrey Robertson, first president of the U.N. Special Court for Sierra Leone, and author of Mullahs without Mercy and The Massacre of Political Prisoners in Iran, 1988, has spoken in-depth on the killings, which he calls “a crime against humanity that can be classified as genocide.”[20] He said in his speech:

Firstly, the practical reason…The fatwa issued by Khomeini began this way: “Since the treacherous MEK do not believe in Islam, and whatever they say stands from hypocrisy, they have become renegades and since they wage war on God.” … As I read this fatwa’s translation, it became clear that a religious reason was the primary reason these people were killed. This is the principal reason, “waging war on God” and “Mohareb.”

These were the religious reasons. It goes on to reveal the political motivations of the massacre. Since its foundation, the MEK was distinguished from Khomeini’s ideology due to their diverse and liberal interpretation of Islam … Khomeini went on …”It is naive to show Mercy to Moharebs, those who wage war on God. The decisiveness of Islam before the enemies of God is among the unquestionable tenets of the Islamic regime.” So here is a bureaucracy imposing the death penalty and goes on, “kill them with revolution courage and rancor these enemies of Islam, must be most ferocious against the infidels.”[21]

The Specter of the Massacre

Although a first in its kind for the mullahs’ regime, Hamid Noury’s trial and sentencing in Sweden harms the ruling clerics in Iran in several ways. First, the daily coverage of testimonies of more than thirty victims of the 1988 massacre, broadcast on several Farsi satellite and online services, creates a problem for the regime within Iranian civil society. On July 14, 2022, the court condemned Noury to life imprisonment, which may set a precedent that would prohibit the highest ranking authorities of Iran from travelling to Europe or elsewhere in the free world.

Ebrahim Raisi himself is one of the first victims. He was supposed to take part in the COP26 summit on the environment in Glasgow. A complaint against him filed by five survivors of the 1988 massacre with the Scottish police may have prompted him to change his mind. Simultaneously with an October 13 press conference held in Glasgow, the Iranian foreign spokesman denied any intention by Raisi to take part in the summit, despite an invitation from the U.N. to heads of states in over two hundred countries.

The latest development is a Swiss federal court ruling ordering Swiss prosecutors to investigate the 1990 assassination of Kazem Rajavi, the representative in Switzerland of the National Council of Resistance of Iran, as a “crime against humanity and genocide.”[22]The murder case, which was going to be shelved on prescription grounds, is considered a continuation of the 1988 massacre. An international arrest warrant against the former Iranian minister of intelligence and security, Ali Fallahian, would thus be renewed along with thirteen other Iranians identified by the Swiss police as perpetrators of Rajavi’s assassination in Geneva.

Conclusion

The ascent to the country’s presidency of Ebrahim Raisi has shed new light on the execution of several thousand prisoners, members of the MEK, as a result of a fatwa by Iran’s then-supreme leader Khomeini. The arrest of Hamid Noury, a notorious prison official who played a pivotal role in the 1988 massacre along with Raisi, threw a further spotlight on the massacre. In the words of Geoffrey Robertson, president of the U.N. Special Court for Sierra Leone, the 1988 killings are “a crime against humanity” and a “genocide.” However, a strong international reaction to the massacre has never materialized.

Yet, daily coverage of the testimonies of survivors of the massacre continues to create problems for the regime. And the Swedish court’s verdict condemning Noury to life imprisonment sets a precedent that has already affected travel by Iranian officials in Europe or elsewhere in the free world. Still, the culture of impunity that existed in Iran in 1988, continues today.

About the author: Hamid Enayat is an Iranian political analyst based in France.

Source: This article was published by Middle East Quarterly, Summer 2023

[1]”Involvement of Iran’s Former Diplomats on Covering Up the 1988 Prison Massacres,” Amnesty International, London, Feb. 6, 2023.

[2] The Oberlin Review (Ohio), Feb. 17, 2023.

[3] Author interview with Gholamhossein Karbaschi, then-special secretary to Ali Khamenei, later Tehran’s mayor, May 1979.

[4] Report No. 3, Judiciary Committee of the National Council of Resistance of Iran, Paris, July 27, 2021.

[5] Mahmoud_Royaie, Twitter.

[6] “Khomeini’s Fatwa Ordering the 1988 Massacre in Iran’s Prisons,” Justice for Victims Of 1988 Massacre in Iran (hereafter, JVMI), Sept. 28, 2016.

[7] La Monde (Paris), Mar. 1, 1989, reprinted in Iran Focus, Aug. 2, 2010; “Iran: The specter of a little-known genocide,” Solicitors Journal and International In-house Counsel Journal, Cambridge, U.K., June 14, 2022;

[8] “Iran: The specter of a little-known genocide.”

[9] BBC Persian, n.d.

[10] BBC Persian, n.d.

[11] “Letter Of Ahmad Khomeini To His Father And The Latter’s Response,” JVMI, Sept. 1, 2016.

[12] Eric David, “Iran: 1988 Massacre and Genocide—No to impunity, yes to accountability,” Aug. 27th International Conference, International Committee in Search of Justice, online, Aug. 30, 2021; see, also, “Experts testify in trial of Iranian regime operative over his role in 1988 massacre,” People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran, Mar. 26, 2022.

[13] “Iran: The specter of a little-known genocide”; see also, “Open Letter to UN Seeking Commission Of Inquiry Into Iran’s 1988 Massacre,” JVMI, May 4, 2021.

[14] “Iran: Blood-soaked secrets: Why Iran’s 1988 prison massacres are ongoing crimes against humanity,” Amnesty International, Beirut, Dec. 4, 2018.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Interactive Map of Mass Graves from Iran’s 1988 Massacre (With Photos),” JVMI, Oct. 24, 2017.

[18] “Iran: Ill-treated for seeking truth and justice: Maryam Akbari Monfared,” Amnesty International, Beirut, Aug. 27, 2021

[19] “Iran: New evidence reveals deliberate desecration and destruction of multiple mass gravesites,” Amnesty International, Beirut, Apr. 30, 2018.

[20] Mansoureh Galestan, “Iran: The 1988 Massacre of Political Prisoners Amounts to Genocide,” National Council of Resistance of Iran, Paris, Aug. 29, 2021.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Swiss Tribunal Pénal Federal court decision, Sept 23, 2021.