Spain’s Turmoil And Europe’s Crisis – Analysis

By FPIF

The problems facing the Spanish left mirror the crisis engulfing Europe.

By Conn Hallinan*

The current chaos devouring Spain’s Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) has mixed elements of farce and tragedy. However, the issues roiling Spanish politics reflect a general crisis in the European Union (EU) and a sober warning to the continent: Europe’s 500 million people need answers, and the old formulas are not working.

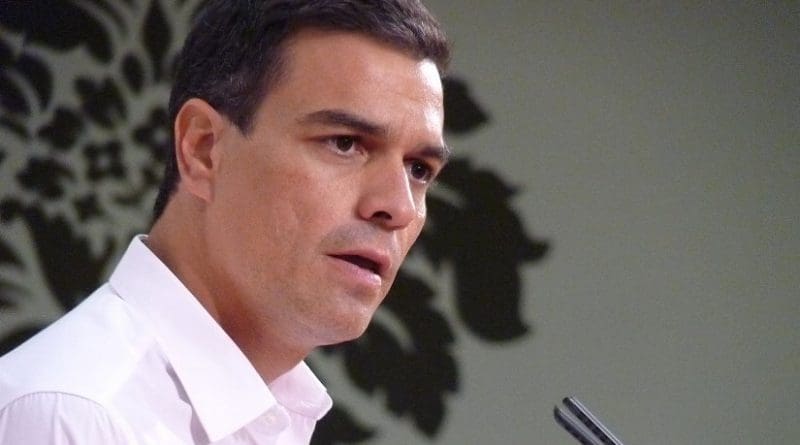

On the tragedy side was the implosion of a 137-year-old party that at one point claimed the allegiance of half of Spain’s people now reduced to fratricidal infighting. The PSOE’s embattled general secretary, Pedro Sanchez, was forced to resign when party grandees and regional leaders organized a coup against his plan to form a united front of the left.

The farce was street theater, literally: Veronica Perez, the president of the PSOE’s Federal Committee and a coup supporter, was forced to hold a press conference on a sidewalk in Madrid because Sanchez’s people barred her from the party’s headquarters.

There was no gloating by the Socialists’ main competitors on the left. Pablo Iglesias, the leader of Podemos, somberly called it “the most important crisis since the end of the civil war in the most important Spanish party in the past century.”

There’s no question that the party coup is a crisis for Spain. But the issues that prevented the formation of a working government for the past nine months are the same ones Italians, Greeks, Portuguese, Irish—and before they jumped ship, the British—are wresting with: growing economic inequality, high unemployment, stagnant economies, and whole populations abandoned by Europe’s elites.

Post-Electoral Crisis

The spark for the PSOE’s meltdown was a move by Sanchez to break the political logjam convulsing Spanish politics. The current crisis goes back to the December 20, 2015 national elections in which Spain’s two traditional parties—the rightwing People’s Party (PP), led by Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, and Sanchez’s Socialists—took a beating. The PP lost 63 seats and its majority, and the PSOE lost 20 seats. Two new parties, the leftwing Podemos and the rightwing nationalist party Ciudadanos, crashed the party, winning 69 seats and 40 seats, respectively.

Although the PP took the most seats, it was not enough for a majority in the 350-seat legislature, which requires 176. In theory, the PSOE could have cobbled together a government with Podemos, Catalans, and independents, but the issue of Catalonian independence got in the way.

The Catalans demand the right to hold a referendum on independence, something the PP, the Socialists, and Ciudadanos bitterly oppose. Although Podemos is also opposed to Spain’s richest province breaking free of the country, it supports the right of the Catalans to vote on the issue. Catalonia was conquered in 1715 during the War of the Spanish Succession, and Madrid has oppressed the Catalans’ language and culture ever since.

The Catalan issue is an important one for Spain, but the PSOE could have shelved its opposition to a referendum and made common cause with Podemos, the Catalans and the independents. Instead, Sanchez formed a pact with Ciudadanos and asked Podemos to join the alliance.

For Podemos, that would have been a poison pill. Podemos is the number one party in Catalonia largely because it supports the right of Catalans to hold a referendum. If it had joined with the Socialists and Ciudadanos it would have alienated a significant part of its base. Bearing this in mind, Sanchez might have reasoned that Podemos’ refusal to join with the Socialists and Ciudadanos would hurt it with voters. Sanchez gambled that another election would see the Socialists expand at the expense of Podemos and give it enough seats to form a government.

That was a serious misjudgment. The June 26 election saw PSOE lose five more seats in its worst-ever performance. Ciudadanos also lost seats. Although Podemos lost votes—at least 1 million—it retained the same number of deputies. The only winner was the Popular Party, which poached eight seats from Ciudadanos for an increase of 14. However, once again no party won enough seats to form a government.

The current crisis is the fallout from the June election. Rajoy, claiming the PP had “won” the election, formed an alliance with Ciudadanos and asked the PSOE to either support him or abstain from voting and allow him to form a minority government. Sanchez refused, convinced that allowing Rajoy to form a government would be a boon to Podemos and the end of the Socialists.

There is a good deal of precedent for that conclusion. The Greek Socialist Party formed a grand coalition with the right and was subsequently decimated by the leftwing Syriza Party. The German Social Democratic Party’s alliance with the conservative Christian Democratic Union has seen the once mighty organization slip below 20 percent in the polls. England’s Liberal Democratic Party was destroyed by its alliance with the Conservatives.

Sanchez was forced out ostensibly because he led the Socialists to two straight defeats in national elections and oversaw the beating the PSOE took in recent local elections in the Basque region and Galicia. But the decline of the Socialists predated Sanchez. The party has been bleeding supporters for over a decade, a process that accelerated after it abandoned its social and economic programs in 2010 and oversaw a mean-spirited austerity regime.

The PSOE has long been riven with political and regional rivalries. Those divisions surfaced when Sanchez finally decided to try an alliance with Podemos, the Catalans, and independents, which suggests he was willing to reconsider his opposition to a Catalan referendum. That’s when Susana Diaz, the Socialist leader in Spain’s most populous province, Andalusia, pulled the trigger on the coup. Six out of seven PSOE regional leaders backed her. Diaz will likely take the post of general secretary after the PSOE’s convention in several weeks.

The Andalusian leader has already indicated that she will let Rajoy form a minority government. “First we need to give Spain a government,” she said, “and then open a deep debate in the PSOE.” Sanchez was never very popular—dismissed as a good looking lightweight—but the faction that ousted him may find that rank-and-file Socialists are not overly happy with a coup that helped usher in a rightwing government. This crisis is far from over.

In the short run the Popular Party is the winner, but Rajoy’s ruling margin will be paper-thin. Most commentators think that Podemos will emerge as the main left opposition. Although the Socialists did poorly in Galicia and the Basque regions, Podemos did quite well, an outcome that indicates that talk of its “decline” after last June’s election is premature. In contrast, Ciudadanos drew a blank in the regional voting, suggesting that the party is losing its national profile and heading back to being a regional Catalan party.

Soul Searching on the Left

Hanging over this is the puzzle of what went wrong for the left in the June election, particularly given that the polls indicated a generally favorable outcome for them. It is an important question because although Rajoy may get his government, few are willing to bet that it will last very long.

Part of the outcome was its dreadful timing: two days after the English and the Welsh voted to pull the United Kingdom out of the European Union. The “Brexit” was a shock to all of Europe and hit Spain particularly hard. The country’s stock market lost some $70 billion, losses that fed the scare campaign the PP and the PSOE were running against Podemos.

Even though Podemos supports EU membership, the right and the center warned that, if the leftwing party won the election, it would accelerate the breakup of Europe and encourage the Catalans to push for independence. Brexit pushed fear to the top of the agenda, and when people are afraid they tend to vote for stability.

But Podemos lost a measure of support because it confused some of its own supporters by moderating its platform. At one point Iglesias even said that Podemos was “neither right nor left.” The Party abandoned its call for a universal basic income, replacing it with a plan for a minimum wage, no different than the Socialist Party’s program. And dropping the universal basic income demand alienated some of the anti-austerity forces that still make up the shock troops in ongoing fights over poverty and housing in cities like Madrid and Barcelona.

Podemos was also hurt by Spain’s undemocratic electoral geography, where rural votes count more than urban ones. It takes 125,000 votes to elect a representative in Madrid, 38,000 in some rural areas. The PP and the PSOE are strong in the countyside, while Podemos is strong in the cities.

Podemos had formed a pre-election alliance—“United We Can”—with Spain’s Unite Left (UL), an established party of left groups that includes the Communist Party, but made little effort to mobilize it. Indeed, Iglesias disparaged IU members as “sad, boring, and bitter” and “defeatists whose pessimism is infectious,” language that did not endear IU’s rank and file to Podemos. Figures show that Podemos did poorly in areas where the IU was strong.

The Galicia and Basque elections indicate that Podemos is still a national force. The party will likely pick up those PSOE members who cannot tolerate the idea that their party would allow the likes of Rajoy to form a government. Podemos will also need to shore up its alliance with the IU and curb its language about old leftists (which young leftists eventually tend to become).

The path for the Socialists is less certain.

If the PSOE is not to become a footnote in Spain’s history, it will have to suppress its hostility to Podemos and recognize that two-party domination of the country is in the past. The Socialists will also have to swallow their resistance to a Catalan referendum, if for no other reason than it will be impossible to block it in the long run. Catalan leader Carles Puigdemont recently announced an independence plebiscite would be held no later than September 2017 regardless of what Madrid wants.

The right in Spain may have a government, but not one supported by the majority of the country’s people. Nor will its programs address Spain’s unemployment rate—at 20 percent the second highest in Europe behind Greece—or the country’s crisis in health care, education, and housing.

For the left, unity would seem to be the central goal, similar to Portugal, where the Portuguese Socialist Workers Party formed a united front with the Left Bloc and the Communist/Green Alliance. Although the united front has its divisions, the parties put them aside in the interests of rolling back some of the austerity policies that have made Portugal the home of Europe’s greatest level of economic inequality.

The importance of the European left finding common ground is underscored by the rising power of the extreme right in countries like France, Austria, England, Poland, Greece, Hungry, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Germany. The economic and social crises generated by almost a decade of austerity and growing inequality require programmatic solutions that only the left has the imagination to construct.

One immediate initiative would be to join the call by Syriza and Podemos for a European debt conference modeled on the 1953 London Conference that canceled much of Germany’s wartime debt and ignited the German economy.

But the left needs to hurry lest xenophobia, racism, hate, and repression, the four horsemen of the right’s apocalypse, engulf Europe.

*Conn Hallinan can be read at dispatchesfromtheedgeblog.wordpress.com and middleempireseries.wordpress.com