Atoms For Peace 2.0? On Negotiations Between Israel And Saudi Arabia – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Lior Sternfeld

(FPRI) — In the early 1950s, the Eisenhower administration pushed the Atoms for Peace program forward as part of the American Cold War strategy. The idea was to supply emerging nations with nuclear technology so they could produce energy and run research for medical and civilian purposes—one of the beneficiaries of this program was Iran. Very few people gave any thought to the authoritarian nature of the Pahlavi monarchy, and even fewer gave thought to the fragility of such a regime. All that mattered was Iran’s position in the Cold War and its friendliness to the West. In 1957, Iran launched its nuclear program. Yes, it is the same nuclear program a number of countries have been constantly trying to contain or undo since the beginning of this millennium.

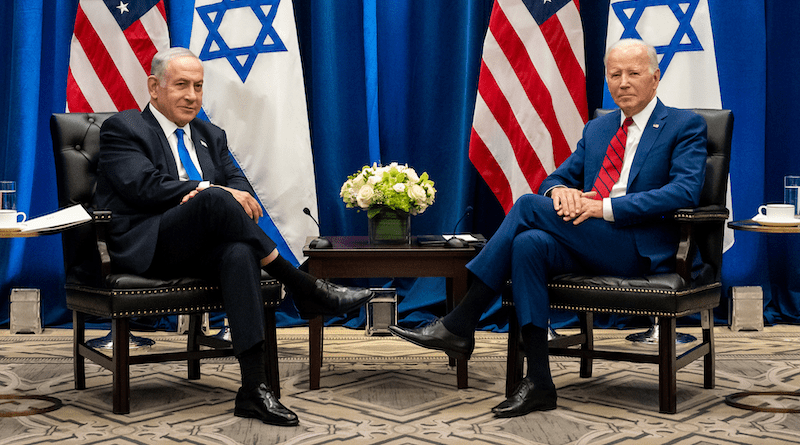

Currently, the US government seems eager to provide another autocratic monarchy in the Middle East with the same kind of gift. The Biden administration is willing to give the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, a ruler not dissimilar to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a nuclear program in exchange for normalizing relations with Israel and cementing American influence in the region. Both fashioned themselves as reformers and Westernizers, the last barrier between the West and Islamic fundamentalism (or communism, in the case of Pahlavi); both were celebrated as forward-thinking, while little regard was given to the abuse of human and civil rights and happily turned a blind eye to the ways they maintained their regime on tactics of authoritarianism and brutality (see the celebrity treatment bin Salman gets in American media outlets). The historical irony is that the advocate of this deal is none other than the politician who spent the past decades convincing the world that no country in the Middle East (other than his own) should have nuclear capabilities–Israel’s embattled prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu.

In recent weeks, details of a potential normalization agreement between Israel and Saudi Arabia have emerged. While there is already vigorous debate about the prospects of this deal, a few working assumptions should be stated. First, a peace agreement is desirable. It is always better to have peace agreements than not having them. Second, peace agreements—by their very definition—end a state of war. Third, there is always a price to pay in a sincere reconciliation process and ending animosity. In that case, what is the price to pay for such an agreement, and what are the likely and unlikely scenarios of each path taken?

How should we understand this current moment between the United States, Iran, Israel, and Saudi Arabia? Following the Abraham Accords, the exchange of military might for normalizing relations with Israel became the basis for diplomacy in the Middle East. In 2020, President Donald Trump was looking for a landmark achievement in foreign policy ahead of his reelection campaign. The arms deals with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the recognition of Morocco’s occupation of Western Sahara, and the removal of Sudan from the state-sponsor of terrorism list seemed reasonable prices to pay for these countries normalizing relations with Israel.

Netanyahu—then as now—pursues these diplomatic initiatives, in part, to divert attention from increasingly loud criticism at home over democratic backsliding and the aggressive expansion of settlements in the Palestinian territories. Of course, Israel was not at war with the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco. In fact, there were already semi-official diplomatic relations in place for many years and ongoing collaboration in many fields. As we have seen with the eruption of yet another round of violence on Saturday, the focus and priority should be a just and peaceful solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict, the one conflict that has an enormous impact on civilian life on both sides of the border and charges an excruciating death toll on a regular basis.

As important as the Abraham Accords are, the real diplomatic prize for Israel would be Saudi Arabia. Although Israel and Saudi Arabia had some harsh relations in the past, the last serious, comprehensive peace proposal was made by Riyadh at the Arab League Summit in Beirut in March 2002, so we can see it as the first genuine attempt of Saudi Arabia to change course with Israel. In the past decade, Saudi and Israeli officials met openly, Saudi Arabia opened its airspace for Israeli carriers for the first time, and both countries collaborated to some extent on countering Iran and its nuclear project. As a result, the normalization of relations seemed to be within reach. Some delays might occur following the current fighting between Israel and Hamas, and any changes in the public opinion may delay it further. However, the official stance of the Saudi royal family was that normalization with Israel must follow a permanent and peaceful solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Why would the Biden administration be so desperate to achieve this goal? During the 2020 presidential primary, President Joe Biden still talked about achieving justice for Jamal Khashoggi and famously called for the Saudi leader to be made into a “pariah.” Arguably, seeking this deal is in line with the US National Security Strategy that was released last fall and is possibly a means to counter rising oil prices.

Netanyahu has the most to gain or lose in this deal. He’s leading the most extreme right-wing coalition to ever rule in Israel. He is not actually leading it. It would be more accurate to say that most of the time, he is dragged behind the even more extreme elements in his coalition, the former convicted terrorist and the current minister of national security, Itamar Ben Gvir, and his party, Jewish Power, and the minister of finance, Betzalel Smotrich of the Religious Zionist Party. He is facing multiple corruption charges and a thirty-eight-week-long protest of his judicial coup and the undoing of the democratic elements of the Israeli government, which he is trying to sell as a set of reforms to the judiciary, which may, in the end, benefit his legal standing. For Netanyahu, finalizing a historic agreement with Saudi Arabia and the United States could temporarily bury all of the negative news in the back pages of the newspaper and show him as the only leader who can bring peace agreements to Israel.

Bin Salman, on his part, surely appreciates that this agreement is a trophy for Biden and Netanyahu. During the UN General Assembly meetings in New York, the Saudi leader gave an interview to Fox News where he reiterated that any nuclear plans for the kingdom would be peaceful. However, he added that if Iran was going to have a bomb, “we have to get one.” This is hardly reassuring. Democratic governments can fall, as we have seen before. But when autocratic governments collapse, it tends to be much messier. The price of securing a Saudi nuclear program will be extremely high, and success is never guaranteed. And it is not like Riyadh has given the world too many good reasons to trust their goodwill.

There is, however, an alternative to giving Saudi Arabia nuclear capabilities. It can provide a pathway to a new, safer, and peaceful Middle East. The balance of power in the region has changed dramatically in the last few years. Iran, with Chinese mediation, signed new agreements with the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain. The three of them are firmly considered US partners, and with at least two of them, Iran had a very high-tension relationship (including firing rockets and missiles). One can see this series of agreements as an Iranian effort to break the ring of isolation around it (which makes it too narrow of a perspective for an extensive set of agreements, to which we can add rapprochement with other American-friendly governments of Sudan, Egypt, and Morocco).

Washington officially responded with suspicion to the news of the deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia. The undertone of the US government and many commentators was that it signaled China’s efforts to undermine America’s sphere of influence in the Middle East. I believe there is another way to interpret it. Iran, by these agreements, in response to Biden’s policies and strategy in the region, and the recent prisoner exchange deal, may be trying to get closer to the United States without saying so formally. If we take the news about the challenges the Chinese government is now facing at face value, Beijing might have overstretched its involvement in the region. Saudi Arabia likely knows the risk of relying on China as a regional partner. Rethinking what Middle Eastern peace looks like includes the idea that peace is not just between rulers and governments. It includes investments in economic growth, the development of civil society, and investments in poorer classes based on the perception of justice. Saudi Arabia will accept American guarantees against possible Iranian aggression. At the same time, the United States can reduce the flames and restore the modified framework of the nuclear agreement with Iran that ensures as much as possible that the benefits of such an agreement go to the Iranian people, and not merely as rewards to elites close to the regime. The caveat is that any future US administration can pull out from any such arrangement and undo whatever progress has been made.

The key to all this (and it was an important component of the original Saudi plan) remains resolving the Israel-Palestine conflict. There are still multiple viable paths possible, and a move in that direction could potentially neutralize the Iranian threat (as Iran repeatedly signed proposals recognizing potential peace treaties between Israel and independent Palestine). The United States should create a mechanism of effective sticks and carrots for Israel and the occupation. American public opinion has shifted in recent years and has more of a balanced understanding of the conflict and its current direction. The message from several large polls is that the automatic bipartisan support Israel had enjoyed is no longer there. Understanding that the occupation is not sustainable and is antithetical to American interests is now shared by over 30 percent of the American public (interestingly, only 9 percent of responders described Israel as a vibrant democracy). If Israel and Palestine make significant progress, it will ensure that Washington does not have to be involved in any future regional conflict and, inevitably, it will create a genuine change in the Middle East, and not just an alliance between unreliable partners.

There are some historical precedents that can help make sense of the current moment. The stability of any government is something that depends on many factors. Famously, President Jimmy Carter depicted Iran at the end of December 1977 as an island of stability in one of the world’s most troubled areas. A year and two weeks later, the Shah would leave the country for good. The goal of US nonproliferation policy should be to consistently reduce nuclear risks in the region. The constellation in the Middle East now allows us to imagine many endings. The easiest and riskiest would be giving Saudi Arabia nuclear facilities in exchange for peace with Israel. But the more long-lasting would be to change the reality in the Middle East, reducing the risk factors, and pushing all the countries to meaningful steps towards regional peace and stability.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy-oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities.

About the author: Lior Sternfeld is a 2023 Templeton Fellow in the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s Middle East Program and an associate professor of history and Jewish Studies at Pennsylvania State University.

Source: This article was published by FPRI