Cold War II? Preserving Economic Cooperation Amid Geoeconomic Fragmentation – Speech

Plenary Speech by IMF First Managing Deputy Director Gita Gopinath at 20th World Congress of the International Economic Association Colombia

Introduction

Good morning. It is an honor to speak at the 20th World Congress of the International Economic Association.

The overarching question of this congress is “Are we at a turning point?”

I believe we are. In fact, I will take this congress’ question a step further and ask: are we on the brink of Cold War II? The historian Niall Ferguson argues that we already are. If so, what would that mean for the global economy? And how can we preserve the gains from economic openness within a more fragmented world?

To answer these questions, I will first briefly trace the history of cross-border trade relations during the twentieth century. I will then examine the parallels and differences between the Cold War and today. I will describe the signs of fragmentation that we see in trade and investment data so far and discuss the potential economic costs should the fault lines deepen. Finally, I will offer three principles for protecting economic cooperation in a more fragmented world.

Pandemic, war, and growing tensions between the two largest economies of the world—the US and China—have undoubtedly changed the playbook for global economic relations. The US calls for “friend-shoring,” the EU for “de-risking,” and China for “self-reliance.” National security concerns are shaping economic policy worldwide.

Meanwhile, the global rules-based system was not built to resolve national security-based trade conflicts. So, we have countries strategically competing with amorphous rules and without an effective referee.

There are benefits for countries of this playbook as they attempt to de-risk their supply chains and strengthen national security. But, if not properly managed, the costs could easily overwhelm these benefits, and potentially reverse nearly three decades of peace, integration, and growth that helped lift billions out of poverty.

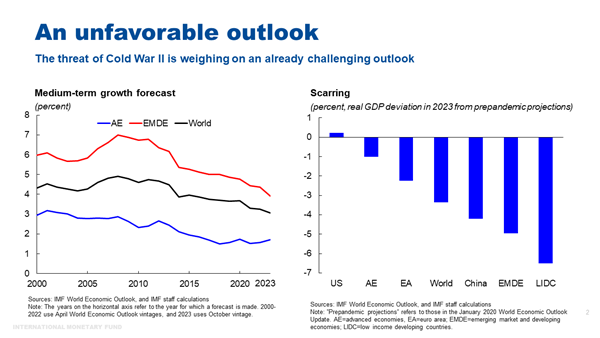

With the weakest global growth prospects in decades—and with disproportionate scarring from the pandemic and war slowing income convergence between rich and poor nations—we can little afford another Cold War.

Some historical perspective

Let’s start by looking at the history. This is not the first time that globalization has come under threat and geopolitical considerations have fragmented global trade and capital flows. [1]

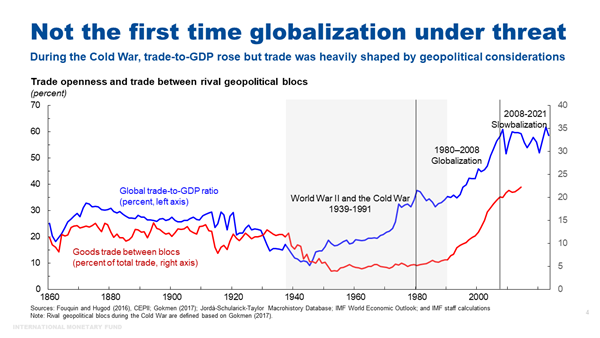

There was an explosion of international trade during the “long” 19th century, a 125-year period beginning with the French Revolution in 1789. But WWI brought that golden era of globalization to an abrupt end with world trade collapsing as a share of income. The protracted economic hardship that followed the war paved the way for the rise of nationalist and authoritarian leaders that later plunged the world into WWII. After WWII, a fragmented bipolar world emerged with two superpowers—the US and USSR—divided by ideology, and political and economic structures. Poised precariously between them was a set of non-aligned countries.

This “Cold War” period, between late 1940s and late 1980s, was not a period of de-globalization as it was marked by rising global trade to GDP driven by the post-war recovery and the trade liberalization policies adopted by many countries in the Western bloc. However, it was a period of fragmentation as trade and investment flows were heavily shaped by geopolitical considerations. Trade between opposing blocs collapsed from around 10-15 percent to less than 5 percent of global trade during the Cold War.

With the end of the Cold War, trade between previously rival blocs expanded rapidly, reaching almost a quarter of world trade in the following decade. The end of the Cold War also coincided with the hyper-globalization period of the 1990s and 2000s: technological innovations, unilateral and multilateral trade liberalization, and geopolitical and institutional changes all coalesced to lift economic integration to levels not seen before.

Since 2008, however, the pace of globalization has stagnated—the so-called slowbalization—with trade to GDP stabilizing as the forces that helped spur hyper-globalization naturally waned. [2]

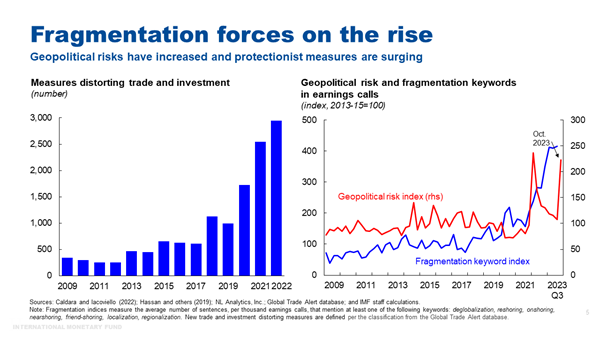

That brings us to the present day. Over the past 5 years, threats to the free flow of capital and goods have intensified as geopolitical risks have grown. Some measures, including tariffs or export restrictions, directly target trade and investment. Other behind-the-border measures indirectly affect trade flows, such as fiscal and financial support to specific domestic sectors and local content requirements.

Around 3,000 trade restricting measures were imposed last year—nearly 3 times the number imposed in 2019.

Multinational firms, in their earnings’ calls, are increasingly discussing issues such as re-shoring, near-shoring, friend-shoring, and deglobalization.

Cold War II?

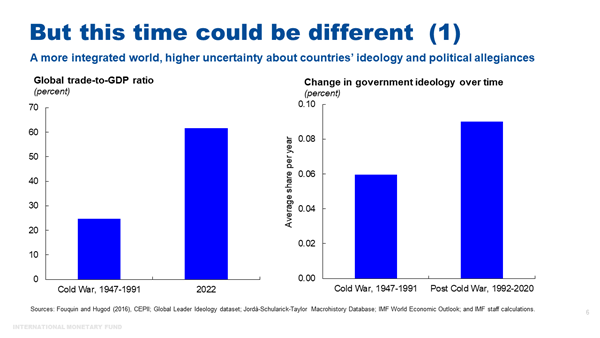

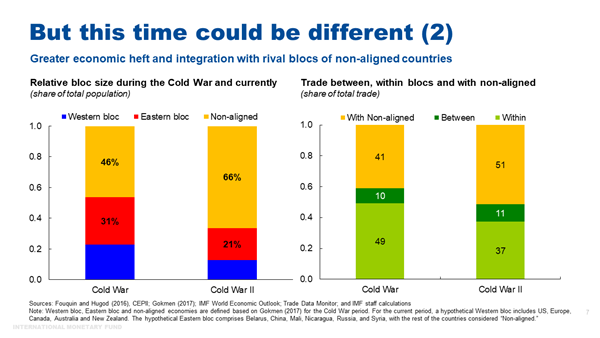

So are we at the beginning of Cold War II? The key driving force is similar—that is the ideological and economic rivalry between two superpowers. In the Cold War it was US and Soviet Union, now it is US and China.[3] But the stage on which these forces are unleashed is fundamentally different along several dimensions.

To start, the degree of economic interdependence between countries now is higher, as economies have become much more integrated into the global marketplace and through complex global value chains. Global trade to GDP is now 60 percent compared to 24 percent during the Cold War. This will likely raise the costs of fragmentation.

There is also greater uncertainty on the bloc with which countries may choose to associate. Within-country swings in the ideology of the political leadership have increased compared to the Cold War era and make it difficult to pin down allegiances. This uncertainty can further raise costs.

On the other hand, the potentially non-aligned countries now have greater economic heft in terms of GDP, trade, and population. [4] For the current period, the analysis considers two hypothetical blocs based on countries’ voting patterns in the UN and include predominantly the US and Europe in the Western bloc and China and Russia in the Eastern bloc, with the rest of the countries considered “non-aligned.” In 1950, the Western and Eastern blocs together accounted for roughly 85 percent of global GDP. The two blocs that we hypothetically have today account for roughly 70 percent of GDP and only one-third of the world’s population. And they have to compete with non-aligned emerging players.

Given their increased economic integration—in 2022 more than half of global trade involved a non-aligned country—they can serve as “connectors” between rivals. They can benefit directly from trade and investment diversion in a fractured global economy and cushion the negative effect of fragmentation on trade, therefore reducing its costs.

Growing fault lines: The facts about fragmentation

Let’s next examine the facts about fragmentation. As you will see, there are signs of growing fault lines.

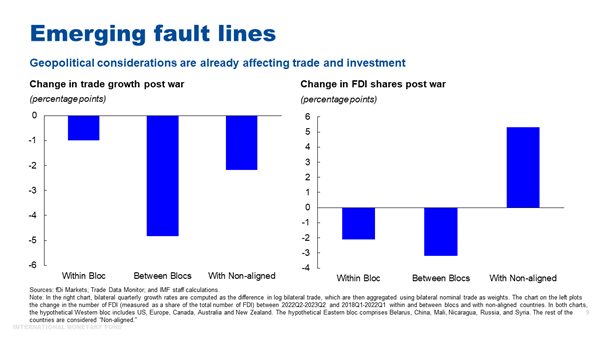

Like the period of the Cold War, we do not see meaningful deglobalization, as the share of global trade in world GDP remains relatively stable. But we are beginning to see signs of fragmentation with meaningful shifts in underlying bilateral trading relations.

While the growth of trade has slowed everywhere after the war in Ukraine, growth between blocs that are not politically aligned has slowed more. Specifically, trade growth within blocs has decreased to 1.7 percent from 2.2 percent pre-war. Trade between blocs has declined from 3 percent pre-war to around -1.9 percent. On net, this generates 3.8 percentage point faster growth in trade within blocs as opposed to between blocs.

Importantly, this pattern is not limited to just trade in strategic sectors—which are most likely to be targeted by policymakers and potentially helps countries de-risk. It also appears in trade of non-strategic products.

There are also clear signs that global foreign direct investment (FDI) is segmenting along geopolitical lines. [5] Announced FDI projects between blocs declined more than those within blocs after the onset of the war in Ukraine, while FDI to non-aligned countries sharply increased. In fact, almost 40 percent of announced FDI projects were in those economies in 2023q3.

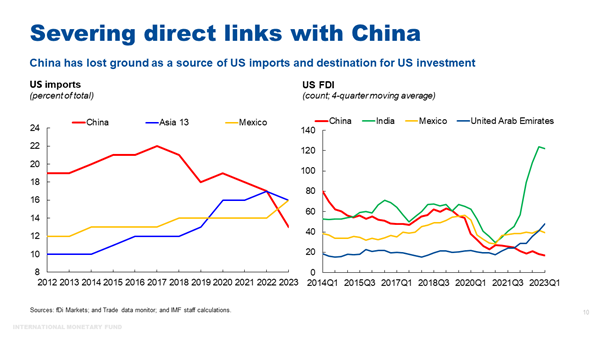

This occurred alongside the resurgence of trade tensions between the US and China, between whom direct links are being severed.

China is no longer the largest trading partner to the US, and its share of US imports has fallen by almost 10 percentage points in 5 years: from 22 percent in 2018 to 13 percent in the first half of 2023. The trade restrictions imposed since the onset of the US-China trade war in 2018 have effectively curbed Chinese imports of tariffed products. [6]

China is also no longer a prominent destination for outward US FDI, losing rank to emerging markets such as India, Mexico, and UAE in the number of announced FDI projects.

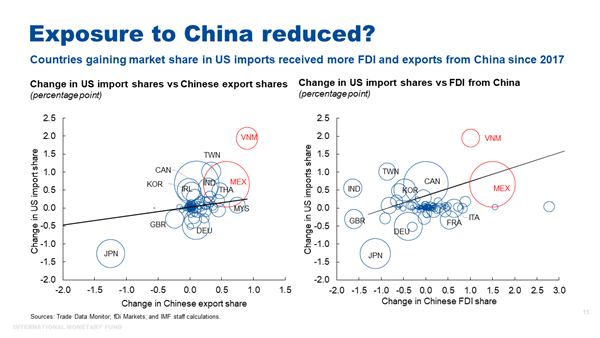

But there is suggestive evidence that direct links between US and China are simply being replaced by indirect links. Countries that have gained the most in US import shares—such as Mexico and Vietnam—have also gained more in China’s export shares. [7] The same countries are also larger recipients of Chinese FDI.

There is growing anecdotal evidence of a set of “connector” countries that are uniquely positioned to benefit from the US strategy of “de-risking” from China. This is due to factors such as their location, natural endowments, and free trade agreements with both sides.

For example, large electronics manufacturers have accelerated relocating production from China to Vietnam given US tariffs on Chinese goods. However, Vietnam sources most inputs from China, while most exports go to the US.

Meanwhile, Mexico eclipsed China as the biggest exporter of goods to the US in 2023. But many manufacturers opening plants in Mexico are Chinese companies, targeting the US market. According to the Mexican Association of private industrial parks, one in five new businesses in the next two years will be Chinese.

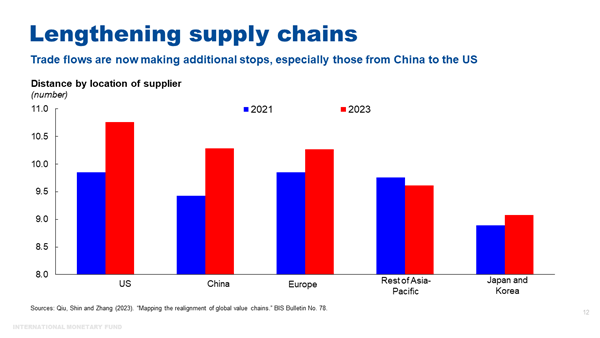

This anecdotal evidence—along with correlations in the data—point to lengthening supply chains. This is supported by a recent BIS study, which examined data from more than 25,000 companies and found that supply chains have lengthened in the last two years, especially those involving Chinese suppliers, and US customers.

In sum, fragmentation is already a reality as geopolitical alignments shape trade and investment flows: a process that will likely continue. But despite efforts by the two biggest economies to cut ties, it is not yet clear how effective they will be in a deeply integrated and connected global economy.

The economic costs of fragmentation.

If fragmentation deepens, what would be the economic cost? And how will those costs be transmitted?

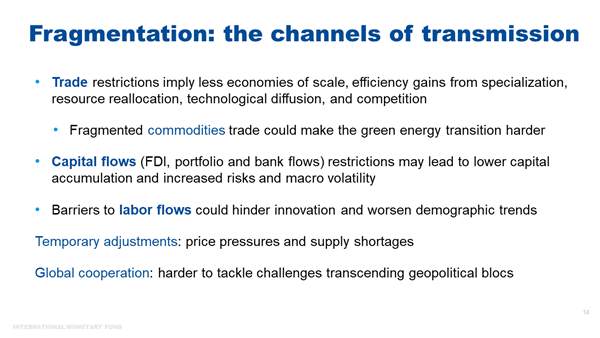

With trade being the main channel through which fragmentation could reshape the global economy, imposing restrictions on trade would diminish the efficiency gains from specialization, limit economies of scale due to smaller markets, and reduce competitive pressures.

The capacity of trade to incentivize within-industry reallocation and generate productivity gains would be stifled. Less trade would also imply less knowledge diffusion, a key benefit of integration, which could also be reduced by fragmentation of cross-border direct investment.

Fragmentation of capital flows would limit capital accumulation—because of lower FDI—and affect the allocation of capital, asset prices, and the international payment system, posing macro-financial stability risks and potentially leading to a more volatile economy.

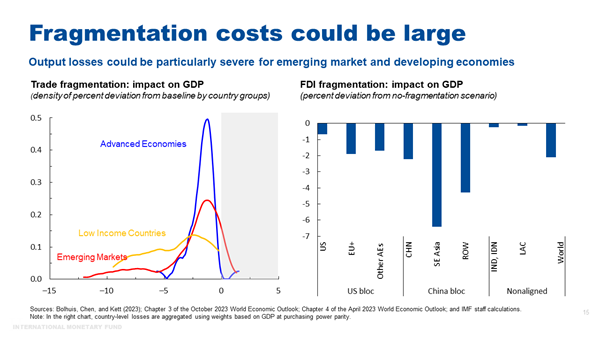

The estimates of the economic costs of fragmentation vary widely and are highly uncertain. But recent and ongoing work at the IMF suggests that these costs could be large and weigh disproportionately on developing countries.

If the global economy were to fragment into two blocs based on UN voting on the 2022 Ukraine Resolution and trade between the two blocs were eliminated, global losses are estimated to be about 2.5 percent of GDP. But depending on economies’ ability to adjust, the losses could reach as high as 7 percent of GDP. At the country level, losses are especially large for lower income and emerging market economies. [8]

FDI fragmentation in a world divided into two blocs centered around the US and China—with some countries remaining non-aligned—could result in long term global losses of around 2 percent of GDP.

As in the case of trade, the losses are larger for less advanced regions—which depend more on inflows from the opposing bloc. [9]

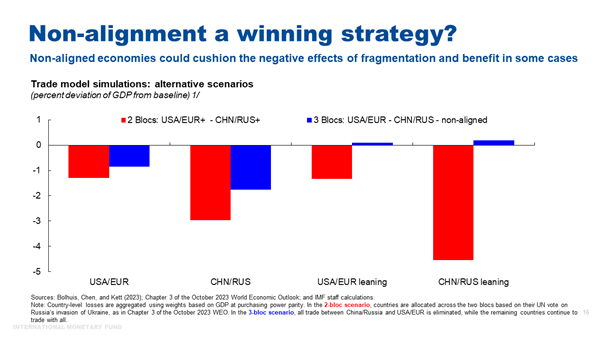

But a lot will depend on how exactly trade and investment fracture. If some economies remain non-aligned and continue engaging with all partners, they could benefit from the diversion of trade and investment.

Our simulations suggest that if only trade between a US-Europe bloc and a China-Russia bloc is disrupted, the remaining economies will see some gains, on average. [10]

Latin American countries are well placed to benefit in such a scenario. For example, Mexico’s proximity with the United States could boost its manufacturing sector, while South America’s commodity exporters could gain market shares.

But if fragmentation worsens, even those who benefit from fragmentation in its mild forms could be left with a larger slice of a smaller pie in an extreme scenario. In short, everyone could lose.

Fragmentation would also inhibit our efforts to address other global challenges that demand international cooperation. The breadth of those challenges—from climate change to AI—is immense.

Recent IMF analysis shows that fragmentation of trade in minerals critical for the green transition—such as copper, nickel, cobalt, and lithium—would make the energy transition more costly. Because these minerals are geographically concentrated and not easily substituted, disrupting their trade would lead to sharp swings in their prices, suppressing investment in renewables and EV production. [11]

What can policymakers do to prevent the worst-case economic scenarios in a full-blown Cold War II?

At this turning point, policymakers face difficult tradeoffs between minimizing the costs of fragmentation and maximizing security and resilience. Pragmatic approaches that preserve the benefits of free trade to the extent possible and safeguard solving global challenges—while minimizing distortions—are needed.

The first best solution, of course, is to avoid fragmentation. But, for the time being, this may be difficult to achieve.

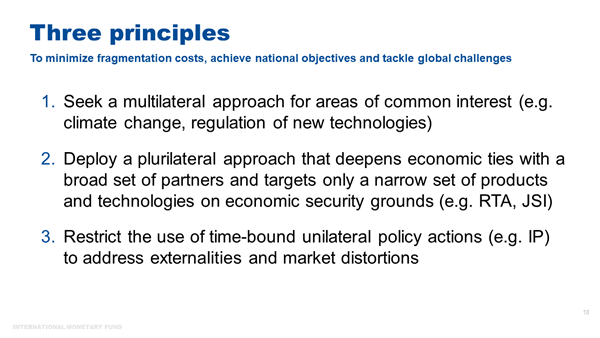

Absent the best-case scenario, we must work to avoid the worst-case scenario and protect economic cooperation in a more fragmented world. Three principles can help:

First, seek a multilateral approach at the very least for areas of common interest. For example, a green corridor agreement could guarantee the international flow of minerals critical for the clean energy transition.

Similar agreements for essential food commodities and medical supplies could ensure minimum cross-border flows in an increasingly shock-prone world. Such agreements would safeguard the global goals of averting climate change devastation, food insecurity and pandemic related humanitarian disaster. [12]

Second, if some reconfiguration of trade and FDI flows is deemed necessary to de-risk and diversify, a non-discriminatory plurilateral approach can help countries deepen integration, diversify, and mitigate resilience risks.

Policymakers should define broadly the set of partners and allies with which to deepen economic partnerships. Plurilateral agreements consistent with the WTO—such as regional trade agreements and joint statement initiatives—while clearly second best, could offer several benefits. These include economies of scale, greater market access, and diversified suppliers, among others. By updating the rules and keeping an open-door policy, such agreements allow new partners to join when they are willing and able to commit to the agreements’ rules and norms.

Recent examples of regional trade agreements (RTA) include the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Several joint statement initiatives are currently underway, including on e-commerce, investment facilitation, and services domestic regulation. In December 2021, 70 WTO members agreed on a WTO-based plurilateral agreement on domestic regulation of services.

Policymakers should target only a narrow set of products and technologies that warrant intervention on economic security grounds. Before deciding to bring production home, they must carefully consider whether there is truly a lack of suppliers from less risky regions and make an objective assessment of the social and economic costs of supply disruptions. This is especially the case for widely used technologies, such as semi-conductors.

Third, restrict unilateral policy actions—such as industrial policies—to addressing externalities and market distortions and be time-bound. Limit their goal to correcting market failures while preserving market forces where they can allocate resources most efficiently.

It is critical to carefully evaluate industrial policies, both in terms of their effectiveness in achieving stated outcomes and associated economic costs, including cross-border spillovers.

Domestically, industrial policies may be hard to limit or roll back given their concentrated benefits and diffused costs.

Internationally, such policies may lead to retaliation, which would deepen fragmentation. According to recent IMF estimates, if China introduces a subsidy, the likelihood that the EU imposes a trade restricting measure within 12 months in response to the subsidy is 90 percent.

An inter-governmental dialogue—or a consultation framework—on industrial policies could help improve data and information sharing and identify the impact of policies, including their unintended consequences across borders. Over time, steady lines of communication could help develop international rules and norms on the appropriate use and design of industrial polices, making it easier for companies to adjust to the new environment.

On each of these three principles, we can look for blueprints from the last Cold War. Throughout that period, the US and Soviet Union made several agreements to avoid nuclear catastrophe. Both superpowers subscribed to the doctrine of mutually assured destruction, knowing that an attack by one would ultimately lead to total annihilation.

If we descend into Cold War II, knowing the costs, we may not see mutually assured economic destruction. But we could see an annihilation of the gains from open trade. Ultimately, policymakers must not lose sight of those gains. It is in their—and everyone’s—best interest to advocate strongly for a multilateral rules-based trading system and the institutions that support it.

Of course, economic integration has not benefited everyone—acknowledging this is critical to understanding additional motivations behind global inward shifts, and domestic policies must adjust to broaden the benefits. But it has helped billions of people become wealthier, healthier, and better educated—since the end of the Cold War, the size of the global economy roughly tripled, and nearly 1.5 billion people were lifted out of extreme poverty.

Conclusion

Let me conclude. While there are no signs of broad-based retreat from globalization, fault lines are emerging as geoeconomic fragmentation is increasingly a reality. If fragmentation deepens, we could find ourselves in a new Cold War.

The economic costs of Cold War II could be large. The world has become much more integrated, and we face an unprecedented breadth of common challenges that a fragmented world cannot tackle.

Yet, even in this new geopolitical reality, policymakers can seek solutions that minimize the costs of fragmentation. The focus should be on pragmatic approaches that preserve the benefits of free trade to the extent possible, safeguard solving global challenges, while achieving domestic goals of security and resilience.

Keeping open the lines of communication, as is being done by the US, China, and EU, can help prevent the worst outcomes from occurring. The non-aligned countries, which are mainly emerging and developing countries, can deploy their economic and diplomatic heft to keep the world integrated. After all, many emerging and developing countries face the biggest losses from a fragmented world, and while some benefit in the early stages of fragmentation, all lose in a full-blown Cold War.

As we consider this “turning point” question over the next few days, I encourage all of us to think about how we can help achieve these solutions—through our research and our collaboration. This will be critical to preserve what we have achieved and face the global challenges ahead.

Thank you.

References

Aiyar, Shekhar, Davide Malacrino, and Andrea Presbitero (2023a). “Investing in Friends: The Role of Geopolitical Alignment in FDI Flows.” CEPR Discussion Paper 18434.

Aiyar, Shekhar, Andrea Presbitero, and Michele Ruta (2023b). “Geoeconomic Fragmentation: The Economic Risks From a Fractured World Economy.” CEPR Press.

Alfaro, Laura, and Davin Chor (2023). “Global Supply Chains: The Looming “Great Reallocation.” NBER Working Paper 31661, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Antràs, Pol (2021). “De-Globalisation? Global Value Chains in the Post-COVID-19 Age,” (2021) ECB Forum: Central Banks in a Shifting World Conference Proceedings.

Attinasi, Maria Grazia, Lukas Boeckelmann, and Baptiste Meunier. 2023. “Friend-Shoring Global Value Chains: A Model-Based Assessment.” European Central Bank Economic Bulletin 2, European Central Bank, Frankfurt.

Bolhuis, Marijn, Jiaqian Chen, and Benjamin Kett. 2023. “Fragmentation in Global Trade: Accounting for Commodities”. IMF Working Papers 23. International Monetary Fund.

Bown, Chad (2022). Four Years Into the Trade War, are the US and China Decoupling. Working paper, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Caldara, Dario and Matteo Iacoviello (2022). Measuring Geopolitical Risk. American Economic Review 112 (4), 1194–1225.

Campos, Rodolfo, Julia Estefania-Flores, Davide Furceri, and Jacopo Timini (2023). Geopolitical fragmentation and Trade.” Journal of Comparative Economics (Forthcoming).

Dang, Alicia, Kala Krishna and Yingyan Zhao. 2023. “Winners and Losers from the U.S.-China Trade War.” NBER Working Papers 31922, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Fajgelbaum, Pablo, Pinelopi Goldberg, Patrick Kennedy, Amit Khandelwal, and Daria Taglioni. 2023. “The US-China Trade War and Global Reallocations.” American Economic Review: Insights (Forthcoming).

Ferguson, Niall. 2020. “Cold War II.” National Review Magazine, December 3, 2020.

Freund, Caroline, Aaditya Mattoo, Alen Mulabdic, Michele Ruta. 2023. “Is US Trade Policy Reshaping Global Supply Chains?” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 10593.

Góes, Carlos, and Eddy Bekkers. 2022. “The Impact of Geopolitical Conflicts on Trade, Growth, and Innovation.” Staff Working Paper ERSD-2022-09, World Trade Organization, Geneva.

Gokmen, Gunes (2017). “Clash of Civilizations and the Impact of Cultural Differences on Trade” Journal of Development Economics, 127, 449-458.

International Monetary Fund. 2023a. “Geoeconomic Fragmentation and Foreign Direct Investment”. Chapter 4, World Economic Outlook, April.

International Monetary Fund. 2023b. “Commodities and Fragmentation: Vulnerabilities and Risks”. Chapter 3, World Economic Outlook, October.

Javorcik, B. Seata, Lucas, Kitzmueller, Helena Schweiger, and Muhammed Yıldırım (2022). “Economic Costs of Friend-shoring.” EBRD Working Paper 274, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Qiu Han, Hyun Song Shin and Leanne Si Ying Zhang (2023). “Mapping the realignment of global value chains.” BIS Bulletin No 73, October 3, 2023.

[1] Deglobalization refers to the retrenchment of economic flows between countries. Typically measured as a reduction in the world trade (or investment) to GDP ratio, deglobalization could be driven by policy choices (such as the imposition of tariffs), secular trends (such as the structural transformation towards less-traded parts of the economy), and the waning of forces that helped spur the rapid integration of economies until the mid-2000s (such as the reduction in transport costs, the break-up of production processes across countries, technological advances, and the like). Fragmentation, on the other hand, refers to policy-induced redirection of trade and investment flows that may or may not be associated with a decline in world trade to GDP.

[2] See Antras (2021).

[3] During the Cold War, the world was divided into two blocs, a Western and Eastern bloc, and a set of non-aligned countries. The analysis uses the bloc definition based on Gokmen (2017). The Western bloc includes Andorra, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Philippines, Portugal, San Marino, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States. The Eastern bloc includes Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bulgaria, China, Cuba, Czech Rep., Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Lao People’s Dem. Rep., Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Mongolia, North Korea, Poland, Romania, Russia (USSR), Slovakia, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Vietnam. The remaining countries are considered “non-aligned.”

[4] For the current period, the analysis considers a hypothetical Western bloc, including US, Europe, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The hypothetical Eastern bloc comprises Belarus, China, Mali, Nicaragua, Russia, and Syria. The rest of the countries are considered “non-aligned.”

[5] See Aiyar et al. (2023a).

[6] See Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal (2022) for a survey of the literature, as well as Alfaro and Chor (2023), Bown (2022), Freund et al. (2023),.

[7] See also Alfaro and Chor (2023), Dang et al. (2023) and Freund et al. (2023).

[8] See Bolhuis, Chen and Kett (2023). A growing literature also points to large costs from trade fragmentation and the resulting reshaping of GVCs (see, among others, Aiyar et al. 2023b; Attinasi et al. 2023; Campos et al. 2023; Goes and Bekkers 2023, Javorcik et al. 2022).

[9] See Chapter 4 of the April 2023 World Economic Outlook.

[10] Aggregate global output changes would still be negative in this scenario, due to the inefficiencies associated with trade restrictions even if applied only to a subset of the world economies.

[11] See Chapter 3 of the October 2023 World Economic Outlook.

[12] The global community could learn from the exemption of humanitarian food purchases from export restrictions established at the twelfth WTO Ministerial Conference in 2022.