How Failed International Cooperation Amplifies Virus Damage – OpEd

As the downgrades of the economic outlook for US, China and worldwide are about to begin, the virus outbreak may be steadying. Sadly, much of the economic, xenophobic and virus damage stems for lagging cooperation.

At the end of January, United States declared the 2019 novel coronavirus acute respiratory disease (nCoV ARD) an “unprecedented public health threat” followed by preparations “as if this were the next pandemic.” The unilateral action went against guidance by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Thanks to sensationalist media, the move also unleashed fear across America at the peak of the domestic flu season. Some 22 to 31 million Americans have already been infected with the seasonal flu, requiring up to 210,000 to 370,000 hospitalizations and causing 12,000 to 30,000 deaths, according to the CDC. As the Trump administration is preparing a $4.8 trillion budget with big safety-net cuts, it is focusing public attention on the virus outbreak.

Instead of a focus on the epidemiological facts, international headlines have focused on the expected “pandemic,” resulting in pressure campaigns against the WHO and an avalanche of xenophobic anti-Chinese incidents. The net effect will reverberate in downgraded economic outlooks in China, US and worldwide.

Here’s how it happened.

Rising number of cases, rapid outbreak deceleration

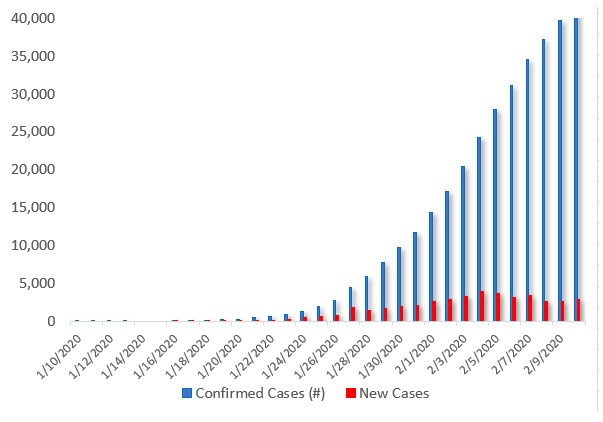

Even reputable media has contributed to misunderstandings. On February 4, New York Times reported: “Deaths in China Rise, With No Sign of Slowdown.” The first part of the sentence was true, but the second was misguided. In reality, the daily increase of newvirus cases in China had just started to decelerate, while the pace of accumulated cases had been decelerating since mid-January.

With the new coronavirus, there are now (2 pm Wuhan time, Feb 11) over 42,600 confirmed cases worldwide, while the number of deaths is more than 1,000. If the current pace prevails, the former figure will soon exceed 50,000, while the latter may climb to 2,000.

And yet, the number of the confirmed cases and deaths has remained relatively low – less than 500 and only 2, respectively – outside China. While these numbers will continue to increase, the low starting-point suggests that China’s costly and draconian measures may have saved many lives within and outside China.

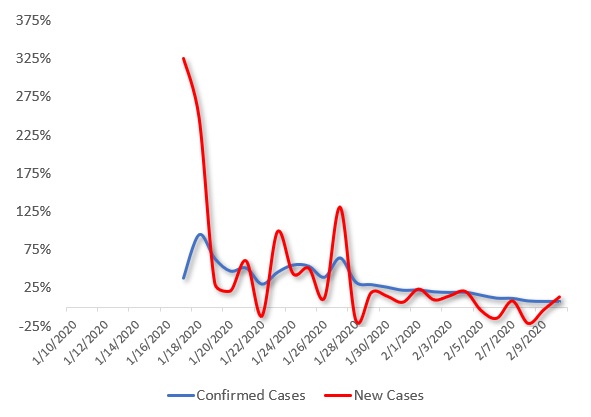

Moreover, the pace of the contagion is changing. The relative increase of the accumulated cases has decreased since mid-January. While the pace peaked at almost 100% after mid-January, it has declined to zero and below (Figure 1a). In turn, new cases increased steadily from mid-January soaring to almost 3,900 on February 4. But since then the numbers have fallen below 2,600 – from daily increase of almost 350% to zero and below (Figure 1b).

Figure Rising Accumulated Numbers, Falling Relative Rates

A) Daily Increase of Accumulated Cases, Jan 10 to Feb 9, 2020

B) Daily Increase of New Cases, Jan 10 to Feb 9, 2020

Source: DifferenceGroup. Data from China’s National Health Commission

While the data could indicate a possible turnaround in the virus outbreak, there is no assurance that the deceleration will prevail. Since viruses can zigzag, these trends do not justify any complacency. And as the Lunar New Year holidays now end in China, new outbreak clusters are still possible, including outside China. But assuming current trends, we may be witnessing a crossroads – despite politicized international coverage.

Instead of virus outbreak, an ‘infodemic’

In late January, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern” (PHEIC) and urged attention to a global health emergency to foster a “coordinated international response.” The PHEIC was not motivated by China, but by the possible effects of the virus, if it would spread to countries with weaker healthcare systems. That’s why WHO has called for a $675 billion initiative to combat future virus outbreaks.

Instead, media hysteria contributed to ugly instances of xenophobia against people of Chinese and Asian descent. On February 2, the misinformation on global scale compelled the WHO to declare the coronavirus an “infodemic,” which “made it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance.”

Worse, WHO leaders were targeted in public pressure crusades, including an online petition campaign calling the WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus to resign. In reality, Tedros, an Ethiopian public-health pioneer, has adhered to WHO guidelines regarding pandemics, supported research on virus causes and tried to foster member states’ cooperation against the outbreak.

The smear campaign is an ugly déjà vu. Amid the 2017 WHO election, Tedros was attacked for alleged cover-up of possible past cholera epidemics in Ethiopia. The odd allegations came from Lawrence Gostin, US law professor who advised the rival UK candidate (and has resurfaced as a critic of China’s anti-virus struggle). In the UN, the African Union dismissed the allegations as an “unfounded and unverified defamation campaign.” But now the same ugly campaign was back.

In contrast to Washington’s demands for WHO to declare the outbreak a “pandemic,” WHO has a six-stage pandemic classification, which requires a pandemic to be fatal, infectious and international. In the last pandemic, the 2009 H1N1 flu outbreak (swine flu), 150,000-300,000 people died around the world. The current outbreak has caused only two deaths outside China (both linked with Wuhan, the virus epicenter).

Oddly, as international coverage focused on China’s alleged conduct, which WHO mainly applauded, it ignored the actual conduct of other states, despite Tedros’s news bomb on February 4. It was not China, but countries outside China that had proved slow in sharing complete information about cases. Despite weeks of crisis and global health emergency, more than 60% of five member countries had failed to provide complete case reports to WHO.

As international cooperation lagged and precious time was lost, economic consequences have grown more severe.

Impact scenarios

After a month of the virus outbreak, three economic scenarios prevail. In the “SARS-like impact scenario,” a sharp quarterly effect, accounting for much of the damage, would be followed by a rebound. The broader impact would be relatively low and regional. The impact on annualized growth would be tolerable.

In China, the 1st quarter would be penalized by a 1.2% reduction to about 5% or less, while the 2nd quarter rebound would offset much (but not all) of the losses. U.S. growth could suffer a 0.4% slowdown of the annualized growth. In Japan, growth would fall closer to 0%. Due to supply chain disruptions, South Korea and Taiwan would take heavier hits. In Hong Kong, the outbreak will extend the technical recession into the 1st quarter. In Southeast Asia, downgrades would reduce growth closer to 4%. Annualized global growth would fall closer to 3.1%.

In the “extended impact scenario,” the adverse impact would last at least two quarters until early summer. In this case, the broader impact would be more severe and have an effect on global prospects, with rebound in the summer. The reductions in the US, China, and Japan would have a significant adverse impact in Asia and the global economy.

In the “accelerated impact scenario,” adverse damage would be far steeper, while a rebound would ensue only toward the end of the summer. The impact on annual growth would prove very significant, with dire repercussions in the global economy.

Today, consensus projections vary between the SARS-like and extended impact scenarios. If we are witnessing a sustained turnaround in new virus cases, there might be some reason for such hopes. Yet, international media coverage, pressures against WHO and lagging international cooperation indicate non-economic forces are fueling economic forecasts, while the risk of the extended impact scenario has increased. Finally, the accelerated impact scenario would undermine most of the post-2008 recovery with severe consequences to global prospects.

No virus outbreak will go by without adverse economic effects. But some of the impending damage could have been reduced with appropriate international cooperation.

The original commentary was released by China-US Focus on Feb. 11, 2020