Contesting China’s Assertiveness In The South China Sea: The US, Japan, And The Philippines – OpEd

For many years tensions in the South China Sea have been simmering. There have been territorial disputes between China and Southeast Asia over the resource-rich waters located there and because of its strategic location. In this analysis I will be evaluating the recent escalation in tensions focusing specifically on the US reaffirmation of its commitment to the Philippines, the trilateral response which contains Japan, and the elaborate power dynamics at work.

The escalation of the US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty

The foundation of the US-Philippine relationship is the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT), which binds each country to come to the other’s defense in case of external aggression. Recent incidents such as the allegation of “highly dangerous maneuvers” by a Chinese vessel near the disputed Second Thomas Shoal have tested the perimeters of this pledge.

China, on multiple occasions dismissing opposing claims from other nations with overlapping territories, has claimed large sections of the South China Sea. These claims are based on historical analysis and the contentious “nine-dash line.” The Philippines is one of many countries that challenge China’s claims, which include Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan. The ongoing clashes between Chinese and Philippine Coast Guard ships, sparking concerns these incidents could escalate, are both a sign of how high tension is and how far it could go.

The US Reassurance and Trilateral Response

President Biden’s recent statement, in which he vowed that a South China Sea attack against the Philippines would invoke the MDT, greatly assuages the Philippines. It reinforces America’s intention to maintain an inclusive order in the area, which China has regularly sought to fragility by way of its proactive effort.

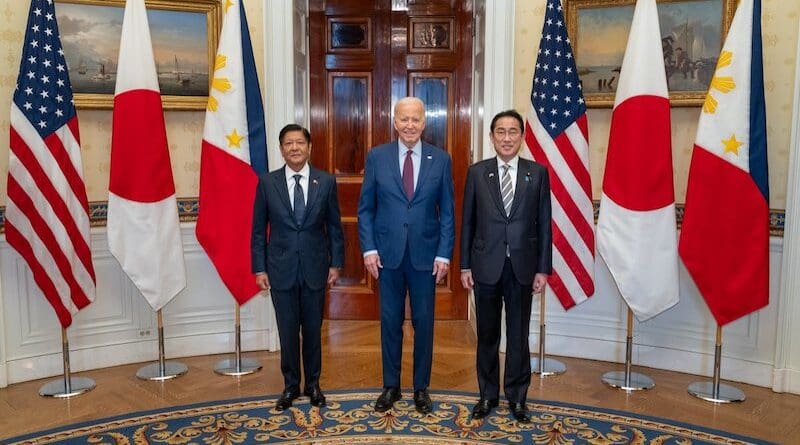

Another subsequent trilateral summit involving the US, Philippines, and Japan once again highlights a united front against this utmost Chinese dominance, the planned trilateral defense cooperation, along with the joint naval exercises is a coordinated attempt at deterrence of any of these actions by the Chinese, this signifies the just announced-same day US flotilla-the increased air defense network and a joint command structure that are the result of the US-Japan agreements. This is also potent symbolically. The announcement that the UK is including upcoming military exercises adds further strength to the existing/in-the-making collective security structure of the region.

China’s response and trying to balance both sides was a way of limiting their stance on the issue. Accusations of wrongdoing in the South China Sea are easily brushed aside by China, which frequently flips the script to blame the US for destabilization. Suspicion of the US presence in the neighborhood is fundamental to China’s belief in its own right to territorial integrity and great power ambitions. It also wants to dominate the region while maintaining economic ties with the US and other Southeast Asian powers. China thereby needs to be assertive while still welcoming cooperation to maintain that balance.

Conclusion

The situation in the South China Sea is as precarious as it is complicated. The United States, the Philippines, and Japan hope to dissuade China from using the threat of force as a trump card by developing a credible military response to its expansionism while keeping their lines of communication open. China, in turn, extols the rights of sovereignty and understands the economic advantages of stability in the region.

At stake is the future trajectory of the Asia-Pacific’s economic growth and strategic landscape, which hinges on the ability of regional countries to manage competing interests in the face of a rising China. In this regard, the outlook is troubling. For starters, there are no regional security institutions that include all disputant parties—all six claimants have staked out mutually exclusive positions and thereby preclude easy resolution of competing claims. If there is any pathway of the confrontational trajectory that the region currently seems poised to follow, it must involve the exercise of self-restraint on the part of the claimant states, as well as a process by which ASEAN unites a wayward China with the claimants in a regional diplomatic rules-based security institution that can mediate disputes and enforce agreements. Open communication, adherence to international laws and norms, and responsible behavior by claimant parties and other regional stakeholders can obviate potential flashpoints and promote continued peace and prosperity for Southeast Asia and beyond. The South China Sea is the bellwether for whether this future is realized or not.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own.

Reference

- Carlyle A. Thayer: [invalid URL removed]. (2016). China’s Aggressive Nationalism: Its Impact on the South China Sea and Regional Security. Routledge.

- Mearsheimer, John J.: [invalid URL removed]. (2010). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. W. W. Norton & Company.

- U.S. Department of State: [invalid URL removed]. U.S. Security Commitment to the Philippines. https://www.foreign.senate.gov/press/dem/release/chair-cardin-applauds-passage-of-state-department-authorization-act-and-other-priorities-in-annual-defense-bill)

- Yong Sheng Wong: [invalid URL removed]. (2015). Competing Claims in the South China Sea. The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR).