Ethnic Reconciliation In Sri Lanka: Another Missed Opportunity – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Roshni Kapur

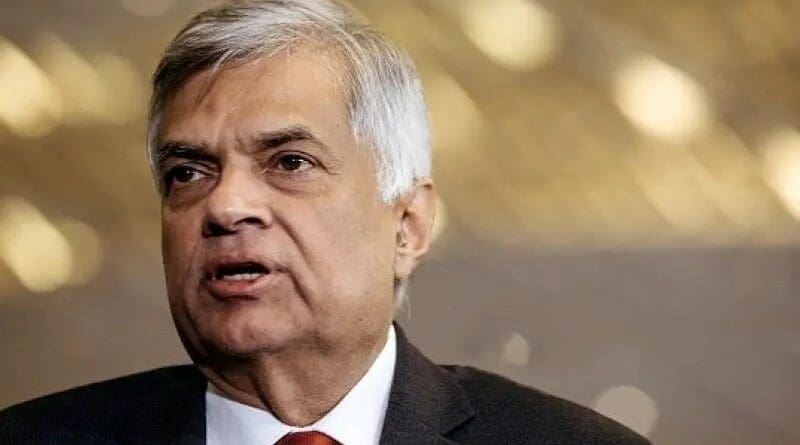

Sri Lankan President Ranil Wickremesinghe initiated an all-party meeting on 13 December 2022 to resolve the longstanding ethnic issue. The President made an ambitious promise to achieve meaningful reconciliation by 4 February 2023—Sri Lanka’s Independence Day. The meeting concluded with Wickremesinghe proposing a two-track approach for greater devolution of powers and resolution of longstanding issues. The all-party conference was viewed as a success on some level because the parties who attended agreed that a power-sharing solution is necessary.

Furthermore, it made way for an informal meeting between the Sri Lankan government and the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), the main Tamil political alliance pushing for power devolution, on 21 December 2022, where they agreed to pardon and release 14 Tamil political prisoners and release all private land under the military’s control in the Northeast. The two sides sought to resolve as many longstanding issues by 31 January 2023 and then announced that they have reached a political agreement by the February deadline.

Scholars such as Jehan Perera expressed optimism that the longstanding ethnic issue may finally be resolved by Independence Day unlike in retrospect. He argued that Wickremesinghe has the capability to bring different groups to the negotiating table and managed to reach the staff-level agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and also pass the 2023 Budget and 21st Amendment in Parliament. The all-party consensus could imply that political parties have suffered the consequences for not supporting the cause and realise that it was high time to resolve the ethnic issue. Several possible reasons prompted Wickremesinghe to push for ethnic reconciliation at this given time including how these reforms are tied to economic assistance, pressure from foreign governments, the European Union (EU), and the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora and an acceptance that the ethnic conflict also contributed to the country’s worst economic crisis.

Unrealistic goals

Although the President’s efforts were applauded for the outreach, a deeper analysis must be done. First, the deadline to resolve a highly complex and contentious issue in a short time was unrealistic. Many previous presidents, including Mahinda Rajapaksa, have made similar pledges but their plans were thwarted by both Sinhala and Tamil nationalists. In February 2023, sections of the Buddhist clergy congregated close to the Parliament and burnt a copy of the 13th Amendment to show their strong opposition to the proposal. While Sinhala nationalists have argued that too much power has been devolved, Tamil nationalists think that it relegates little powers that are not tantamount to a meaningful devolution. There is also the concern that the legislation imposed by India undermines Sri Lankan sovereignty and the unitary state. The 13th Amendment became part of the 1978 Constitution following the signing of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord in 1987 which resulted in the creation of the provincial council system. However, the 13th Amendment has never been fully implemented due to the centralised powers of the executive presidency.

Second, there has been longstanding pressure from foreign governments and regional blocs particularly the United States (US), India, and the EU, to improve its human rights record, including the devolution of powers and accountability for past crimes. The fact that India had a stake in the inception of the 13th Amendment and there are strong cultural and people-to-people linkages between Sri Lankan Tamils and Indian Tamils, allows it to continuously Sri Lanka resolve this issue. The US has also given much importance to issues of human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Colombo. Washington led international efforts against Sri Lanka on ethnic reconciliation and post-war accountability through the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) before exiting from the international bloc in 2018 under Donald Trump. Its rejoining once again puts pressure on Colombo.

The EU resolutions repeatedly stressing that Colombo needs to fulfil its human rights commitments indicate that the latter’s human rights situation is intertwined with trade concessions. The EU temporarily revoked the Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP+) trade benefits from Colombo in 2010 after determining that the latter did not implement three of the UN human rights conventions to be eligible for the scheme. Although Sri Lanka rejoined the GSP+ programme in 2017, it has faced immense scrutiny to honour good governance, the rule of law, and sustainable development. The lack of progress on human rights and ethnic reconciliation jeopardises Sri Lanka’s chances of receiving foreign assistance at a time when it is experiencing its worst economic crisis. New Delhi has emerged as the biggest bilateral donor to Colombo during this current crisis, granting nearly US$3.8 billion in the first half of 2022.

Similarly, the losses from a possible withdrawal of the GSP+ scheme will be immense with the apparel, tobacco, seafood, and rubber sectors being the worst hit. Sri Lankan commodities entering the EU market will become costlier and reduce demand. Sri Lankan exports into the EU were US$3.31 in 2022. Although there have been discussions around lesser reliance on the EU market and diversifying exports, the current focus should be seeking financial assistance to stabilise the economy.

Third, the pressure from human rights organisations, foreign governments, and international agencies demonstrates the lobbying by the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora.[1]These groups have pushed for stronger resolutions at international forums such as the UNHRC about issues of wartime accountability, reconciliation, human rights violations and continued militarisation in the Northwest provinces. The Tamil diaspora has also preserved their narratives of struggle, nationhood, and activism and played a significant role in engaging international actors to continue mounting pressure on Colombo. The networks of diasporic groups have become strong players in international politics whose interests are aligned with those of many foreign actors. Wickremesinghe met a group of the Sri Lankan diaspora during his visit to the UK recognising the pivotal role they play both politically and economically at home.

Crisis of governance and constitutionalism

There is now some level of understanding and acceptance that the country’s ongoing economic crisis is also a crisis of governance and constitutionalism. The latest resolution adopted by UNHRC in October 2022 stated that ‘economic crimes have had an impact on human rights’. The Constitution and institutions have been biased towards the establishment and key interest groups since the 1980s. The political establishment has sought to use the Constitution to increase its power which resulted in a de-democratisation and politicisation of the country’s institutions. Some experts have raised the issue of the executive presidency that was codified in the 1978 Constitution to bring greater economic growth and political stability. However, Colombo has experienced some of the worst episodes of political violence and economic turmoil since then.

Writer D.B.S. Jeyaraj argues that the ethnic conflict has also played a role in Colombo’s economic downfall. Nationalist politics that persisted after the civil war undermined prospects for inter-ethnic solidarity, reconciliation, transitional justice, and development efforts. Nationalist politics has proliferated into the economy, institutions, society and culture. Wickremesinghe’s peace overtures in late 2022 demonstrate that he is cognisant that ethnic reconciliation needs to be addressed to resolve the economic crisis. However, greater devolution of powers, reconciliation, and transitional justice has been viewed as a campaign that would undermine the sovereignty and the unitary state not only by Sinhala-Buddhist nationalists but many from the majority Sinhalese community. The constant international pressure for Sri Lanka to adopt transitional justice and reconciliation measures has made these interventions appear top-down and prescriptive and formed narratives that they are anti-Sinhalese, anti-military, and pro-minority.

Conclusion

The end of the civil war opened the space for genuine reconciliation, transitional justice, power-sharing and devolution of powers. Since many promises have once again not been fulfilled, the Tamil community is convinced that the establishment lacks the political will to resolve this issue or that the President’s efforts are motivated by political and economic reasons. The IMF bailout and the overall economic situation dominate the headlines as the sporadic demonstrations across the country. Many want the government to simply focus on resolving the economic crisis and not complex issues such as reconciliation and transitional justice; there are few prospects of addressing the latter. Although some reforms have been implemented, strong calls have been made to re-democratise the system by ending the executive presidency, restoring checks and balances and independent institutions, and addressing deep-rooted corruption and economic crimes.

*About the author: Roshni Kapur is an independent researcher based in Singapore specialising in geopolitics, conflict resolution, identity politics, and energy transition in South Asia

Source: This article was published by Observer Research Foundation

[1] The Sri Lankan diaspora sent US$454 million in remittances in April 2023.