Recollecting Poitier’s Brush With Africa In Early American Films – OpEd

By IDN

By Lisa Vives*

Not long ago, movies made in Hollywood filmed in major cities in Africa displayed an unapologetic ignorance of even minimal facts about the continent.

Cities named Lagos, Nairobi or Johannesburg became “somewhere in Africa”, anti-colonial sentiments became a “coloured struggle”, and the continent became a “setting and backdrop which eliminates the African as a human factor.”

Such was the critique by Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe describing filmmaking in the 1950s. Professor and author MaryEllen Higgins similarly faulted Hollywood’s Africa. Their films are projections, she said, that reflect national and international investments, both material and ideological.

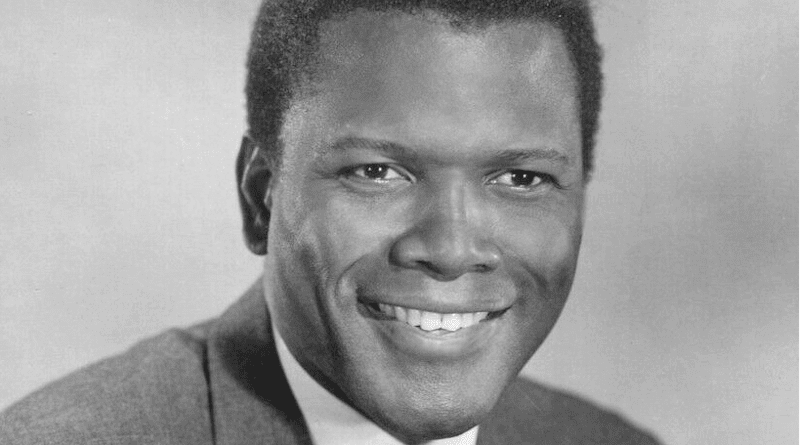

Sidney Poitier, while a pioneer in Hollywood, played it safe in African roles he took on, observed Noah Tsika, associate professor of Media Studies at Queens College, City University of New York.

Poitier’s films promoted a conciliatory, capitalist decolonization process, according to Tsika. These include the films Cry, the Beloved Country (1952), set in apartheid South Africa; The Mark of the Hawk (1957), set in an unnamed African country; Something of Value (1957), also known as Africa Ablaze and set in colonial Kenya; and Mandela and de Klerk (1997), about political negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa.

Still, according to Wesley Morris, Poitier did more with less. “He achieved all he did despite knowing what he couldn’t do… He led more people farther down the road than any other artist.”

What he was up against could be seen in The Mark of the Hawk—a British-American-Nigerian co-production. “Starring Poitier and Eartha Kitt, it was largely shot in Nigeria and depicts an African revolution that is ultimately suppressed, its passions redirected by an American missionary who prescribes “patient faith” in place of violent revolt, says Tsika. An anti-colonial uprising, in his view, is “moving too fast.”

The African characters must “speak African”. A workers’ revolt, evocative of actual Nigerian labour movements, carefully reflects the sort of generalized, deracinated anti-colonial sentiment when the film was made, Tsika observes. The “most basic foreign policy” of the Motion Picture Association of America was to avoid giving offence to any country which provided [Hollywood] with any revenue,” however meagre.

Now, finally, the paternalism of the 50s is facing serious challenge. Critic Sarita Walker of Amplify Africa took on Tears of the Sun, a Nigerian story critics called “shamelessly one-sided with cheesy wooden dialogue”. “I have to point out the problematic view of these kinds of movies,” she wrote, “portraying Africa as a “savage” place in need of “colonization”, “Christianity” and “rescuing”. Have you ever noticed the protagonists are always “white saviours” who are out to save the dying African population?”

“I believe the writers and producers didn’t even bother to visit Africa but just Googled whatever stereotype they could find and threw it in the movie.”

Poitier left a deep impression on South African film producer Anant Singh, (Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, Sarafina!, Cry, The Beloved Country) with whom he had a long-enduring friendship. Singh shared a memory: “I called him in 1985 when I needed help in Hollywood and he said, ‘come whenever you’re here’, and invited me to his house for lunch,” Singh recalled. “He was a huge inspiration to me…growing up under apartheid, most of his films were banned in South Africa…his work lived through those films.”

very nice story too hear this si cool