Iran: The ‘Spirit Of A Spiritless World’ – OpEd

On the occasion of the thirty seventh anniversary of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, we are compelled to revisit the unique insights of Michel Foucault, the late French philosopher, who observed the revolution first-hand and praised it as a liberation struggle with global connotations. As millions of Iranians across the nation partake in mass rallies to commemorate the revolution that dislodged a corrupt, US-backed monarchy with the blood, honor, courage and determination of an entire nation led by a “mythical chief,” to borrow from Foucault, the debate about this historical event and its significance and ranking in the annals of modern world revolutions persist.(1)

Some historians, such as Theda Skocpol, have compared the Iranian revolution to the French and Russian revolutions as representing a landmark historical event ushering in the socio-political transformation of Iran while re-mapping the geopolitical landscape of the region. Foucault, on the other hand, detected the revolution’s novelty at the crossroads of tradition and modernity: ” It is something very old and also very far into the future, a notion of coming back to what Islam was at the time of the Prophet, but also of advancing toward a luminous and distant point where it would be possible to renew fidelity rather than maintain obedience.” At the same time, Foucault drew attention to the trans-Iran, i.e., global, dimensions of the revolution and maintained that the revolution aims not simply to lift the chain on the Iranian people, but also “the weight of whole world order.” In other words, he recognized it as a part and parcel of a global “revolt of masses” against global hierarchies, injustices, oppression, and hegemonic powers.

Nearly four decades later, Foucault’s premonitions about the Islamic Revolution appear to have been exonerated, despite the severe criticisms by certain European intellectuals, many of whom had naively expected the revolutionary clergy to simply pave the way to other, more organized groups. Indeed, the notion of “Islamic populism” as a transitional phenomenon still persists in the scholarly literature, predicated on the eventual evaporation of Islamic utopianism and the return of ‘secular politics’ as the telos of Iranian history. Typically, such analyses suffer from their own utopianism, secular bias, narrow rationalities, and their underestimation of the mobilization potential of Islamist ideology that, in Iran’s case, has blended theocracy with democracy. The peculiar institutional specificity of the Islamic Republic, its evolution compared to the past by institutionalizing regular elections in a multi-layered and complex new polity featuring checks and balances among the branches of government, etc., requires close scrutiny, just as the various defects and shortcomings of the post-revolutionary society need to be carefully studied in terms of their internal and external sources.

The revolution’s so many tumults, such as the American hostage crisis, the devastating long war with neighboring Iraq, the on-going struggles for reform, foreign intervention, the Western sanctions, and so on, have on the whole justified the revolution’s grandeur– that has followed its anti-hegemonic logic unabated, albeit with new twists and nuances dictated by the complex regional realities. As is well-known, the 1979 revolution prompted a new level of American military interventionism in the Middle East under the guise of the Carter Doctrine that discarded the previous Nixon Doctrine, which relied on local client states, above all Iran and Saudi Arabia, to maintain regional stability.

With its immense popularity, charismatic leadership and an inner yearning to expand its horizon beyond Iran’s borders by virtue of its Third World Islamist liberation ideology, the revolution was the harbinger of significant changes. This was not only in Iran, but also in the behavior of American power, the patron of so many client states in the Persian Gulf which were confronted with the prospect of Iran exporting its revolution. Over time, Iran’s influence has spread to many parts of the Middle East — Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Bahrain, Yemen, and elsewhere.

The revolution’s founding father, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, deserves a spot next to other modern revolutionary leaders such as Russian Vladimir Lenin, China’s Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh of Vietnam, Mahatma Gandhi of India and Fidel Castro in Cuba. The ‘cult of Imam,’ as it is referred to today, is a rich ideological repository of self-identity that emphasizes authenticity, autonomy, and self-empowerment, along with a natural sympathy for the downtrodden, the oppressed, the so-called ‘disinherited of the world,” thus giving it the impression of a third worldist liberation movement — that needs to continuously reproduce its initial revolutionary elan in order to remain vital and dynamic, i.e., a liberation from ‘Weber’s bureaucratic cage,’ to paraphrase Foucault.

Therefore, it comes as little surprise that today Iran finds itself in alliance with other Third World countries such as Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua and Bolivia, representing an important anti-hegemonic pattern of politics in world affairs. This small cluster of nations, together with a number of other countries such as South Africa, represent a vanguard of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), that has grown from 77 nations to over 120 nation-states today. Without doubt, the future of NAM rests to some extent on its ability to articulate a sound global counter-hegemonic strategy featuring its own version of “smart power.” Case in point, as the rotating president of NAM, Iran has been able to push the disarmament agenda of NAM, and it has officially denounced nuclear weapons, thus adding another global dimension to the post-revolutionary global mission.

There are, however, multiple challenges facing Iran today, the generational changes, the seducement of Western culture for the younger generation, the rampant class inequality requiring the revisiting of the revolution’s redistributive agenda, the external pressures and threats highlighted by the Islamic State (Daesh), the alliance of conservative, counter-revolutionary Arab states in its vicinity, the overcrowding of Persian Gulf with Western military armada, Israel’s nuclear monopoly in the Middle East, etc.

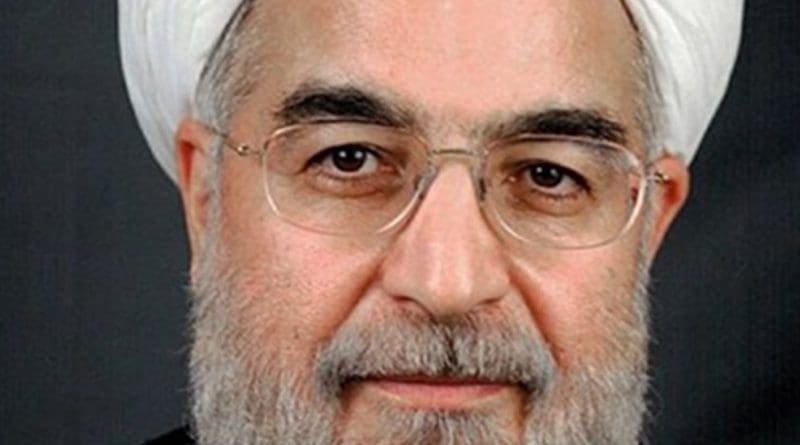

Indeed, the wealth of Iran’s national security worries is quite daunting, even in the post-nuclear agreement milieu, which has opened a new chapter of relations between Iran and Europe, in light of the recent European tour of President Hassan Rouhani, who is determined to reconstruct Iran’s relations with the international community by promoting free trade, foreign investment, and privatization. Rouhani’s challenge, however, is to strike a fine balance between and among the multiple agenda of the Islamic Republic, which as stated above includes a redistributive economic populism reflected in the government’s budgetary priorities such as subsidies and welfarist policies. A purely “post-populist” turn in Iran’s economic agenda is, ideologically speaking, unattractive and does not correspond with the revolution’s raison d’etre. Rather, a new ‘neo-populism’ needs to be crafted, one that assures sustained popular mobilization within the parameters of Iran’s oil-induced capitalism.

Notes:

(1) For more discussions of Foucault and the Islamic Revolution, see Afrasiabi, “Islamic Populism,” Telos: http://journal.telospress.com/content/1995/104/97.abstract