Jewish Tribes In Arabia – OpEd

Rabbi Reuven Firestone is a Professor of medieval Judaism and Islam at a Reform Judaism seminary, and an affiliate professor at the USC School of Religion. He served as Vice President of the Association for Jewish Studies and President of the International Qur’anic Studies Association. Professor Firestone writes that in addition to their ancient homeland of the Land of Israel, Jews had become scattered into other areas.

“The Assyrian Empire dispersed many Jews to various locations within its realm as early as 733 BCE, and after the destruction of the First (Jerusalem) Temple in 586 BCE. Many Jews were driven into exile to the city of Babylon on the Euphrates River in what is today Iraq. The Bible mentions Jews in Nineveh, Babylon, Susa, Hamath, Cuthah, Gozan, Erech, Nimrud (Calah), Sardis (Sefarad), and Egypt among other locations that would eventually fall within the empires of Islam.

“Epigraphic and literary evidence also supports the existence of a well-established Jewish community in Arabia. Evidence of Jewish communities in both northern and southern Arabia derives from Greek, Roman, and early Christian chroniclers writing from the first through the sixth centuries, and from Hebrew and Arabic inscriptions from roughly the same period.”

A Jewish kingdom was even established in Himyar in southern Arabia in the fifth and sixth centuries, which controlled a number of other regions as well. There is clear evidence of a Jewish presence in the northern areas that straddled Jewish settlement in Palestine and Mesopotamia on the one hand, and the Hijaz, the location of Mecca and Medina, on the other.

“Jewish inscriptions in Hebrew and/or Aramaic script but in either the Aramaic or Arabic language have been found in Måda’in Salih, Taymå’, al-‘Ula, Umm Judhayidh (near Tabuk), and a few other locations. Jews (and Christians) brought their cultural, literary, and religious traditions with them wherever they settled, freely sharing their traditions and practices with local communities. Biblical and rabbinic traditions thus became part of the cultural landscape of pre-Islamic Arabia.

“We know much less about social relations between Muslims and Jews during the early Islamic centuries than in later periods. It was a time in which Muslims were busy forming their most basic institutions of scripture (through the establishment of an official canonized text), tradition (through the collection and organization of the prophetic sunna or teachings and practices of Muhammad), and law (through the formation of Islamic jurisprudence, and the major schools of Islamic law). The Jews who lived in the early Muslim world were also busy consolidating Rabbinic Judaism with its core texts of the Talmud and the legal literature that was just beginning to emerge from it.

“Certainly, given the Jewish historical penchant for recording disasters that affected them, if relations had been very bad we would know about it, so it must be presumed that Jews and Muslims lived together reasonably well under the conditions established in the Muslim world during the early period.

“Relations between Muslims and Jews begin to be better known starting in the ninth century CE. This was the beginning of a period that in places such as Baghdad, Fostat/Cairo, and much of Spain, is sometimes referred to as “the Golden Age” of Muslim–Jewish or Muslim–Jewish–Christian symbiosis.

“Golden” must be considered a relative term, however, since violence and the threat of violence was a central aspect of communal relationships between hierarchies everywhere in the medieval world. Jews as subordinates in the Muslim world clearly suffered social discrimination and occasional violence, there was even the occasional massacre.”

Mark Cohen has established quite clearly, however, that while a utopian “golden age” was a myth, the situation for Jews in much of the medieval Muslim world was significantly better than in most of the medieval Christian world and was one of the most favorable situations for pre-modern Jewry.”

Wikipedia states that the Banu Qurayza (Arabic: بني قريظة; بنو قريظة were a Jewish tribe who lived in northern Arabia until the 7th century CE, at the oasis of Yathrib (now known as Medina).

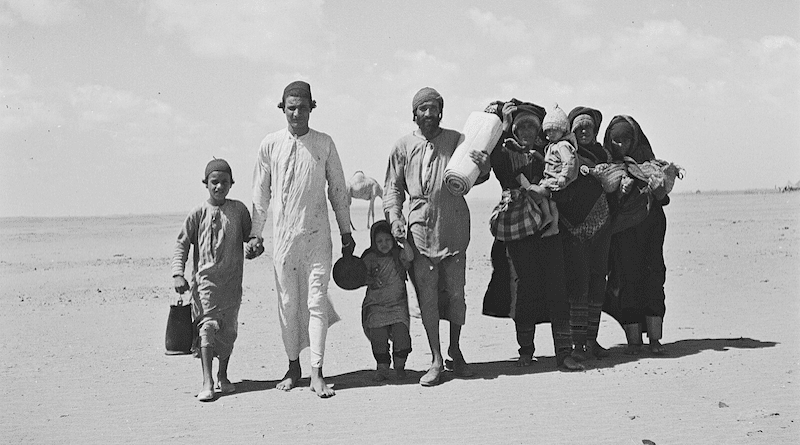

Jewish tribes reportedly arrived in Hijaz in the wake of the Jewish-Roman wars and introduced agriculture, putting them in a culturally, economical and politically dominant position. However, in 5th century CE, the Banu Aws and the Banu Khazraj, two Arab tribes that had arrived from Yemen, gained dominance. When these two tribes became embroiled in conflict with each other, the Jewish tribes, now clients or allies of the Arabs, fought on different sides, the Qurayza siding with the Aws.

In 627, when the Quraysh and their allies besieged the city in the Battle of the Trench, the Qurayza entered into (eventually inconclusive) negotiations with the besiegers. Subsequently, the tribe was charged with treason and besieged by the Muslims commanded by Muhammad. The Banu Qurayza eventually surrendered and all the men, apart from a few who converted to Islam, were beheaded, while the women and children were enslaved.

Extant sources provide no conclusive evidence whether the Banu Qurayza were ethnically Jewish or Arab converts to Judaism. Just like the other Jews of Yathrib, the Qurayza claimed to be of Israelite descent and observed the commandments of Judaism, but adopted many Arab customs and intermarried with Arabs. They were dubbed the “priestly tribe” (kahinan in Arabic from the Hebrew kohanim). Ibn Ishaq, the first author of the traditional Muslim biography of Muhammad, traces their genealogy to Aaron and further to Abraham but gives only eight intermediaries between Aaron and the founder of the Qurayza tribe.

In the 5th century CE, the Qurayza lived in Yathrib together with two other major Jewish tribes: Banu Qaynuqa and Banu Nadir. Al-Isfahani writes in his 10th century collection of Arabic poetry that Jews arrived in Hijaz in the wake of the Jewish-Roman wars; the Qurayza settled in Mahzur, a wadi in Al Harrah. The 15th century Muslim scholar Al-Samhudi lists a dozen of other Jewish clans living in the town of which the most important one was Banu Hadl, closely aligned with the Banu Qurayza.

The Jews introduced agriculture to Yathrib, growing date palms and cereals[1], and this cultural and economic advantage enabled the Jews to dominate the local Arabs politically. Al-Waqidi wrote that the Banu Qurayza were people of high lineage and of properties, “whereas we were but an Arab tribe who did not possess any palm trees nor vineyards, being people of only sheep and camels.” Ibn Khordadbeh later reported that during the Persian domination in Hijaz, the Banu Qurayza served as tax collectors for the shah.

Ibn Ishaq tells of a conflict between the last Yemenite King of Himyar and the residents of Yathrib. When the king was passing by the oasis, the residents killed his son, and the Yemenite ruler threatened to exterminate the people and cut down the palms. According to Ibn Ishaq, he was stopped from doing so by two rabbis from the Banu Qurayza, who implored the king to spare the oasis because it was the place “to which a prophet of the Quraysh would migrate in time to come, and it would be his home and resting-place”.

The Yemenite king thus did not destroy the town and converted to Judaism. He took the rabbis with him, and in Mecca, they reportedly recognized Kaaba as a temple built by Abraham and advised the king “to do what the people of Mecca did: to circumambulate the temple, to venerate and honor it, to shave his head and to behave with all humility until he had left its precincts.” On approaching Yemen, says Ibn Ishaq, the rabbis demonstrated to the local people a miracle and the Yemenites accepted Judaism.

The situation changed after two Arab tribes named Banu Aws and Banu Khazraj arrived at Yathrib from Yemen. At first, these tribes were clients of the Jews, but toward the end of the 5th century CE, they revolted and became independent. Most modern historians accept the claim of the Muslim sources that after the revolt, the Jewish tribes became clients of the Aws and the Khazraj. William Montgomery Watt however considers this clientship to be unhistorical prior to 627 and maintains that the Jews retained a measure of political independence after the Arab revolt.

Eventually, the Aws and the Khazraj became hostile to each other. They had been fighting for almost a century before 620 and at least since the 570s. The Banu Nadir and the Banu Qurayza were allied with the Aws, while the Banu Qaynuqa sided with the Khazraj.

There are reports of the constant conflict between Banu Qurayza and Banu Nadir, the two allies of Aws, yet the sources often refer to these two tribes as “brothers”. Aws and Khazraj and their Jewish allies fought a total of four wars. The last and bloodiest altercation was the Battle of Bu’ath, the outcome of which was inconclusive.

The Constitution, Charter or Covenant of Medina was agreed to during the first or second year after Prophet Muhammad arrived in Medina. About 45-55% of the total population in Medina consisted of pagan Arabs, 30-40% consisted of Jews, and only about 15% were Muslims, at the start of this treaty.

So Prophet Muhammad’s Charter/Covenant of Medina was designed to govern a multi-religious pluralistic society in a manner allowing religious freedom for all. As the Qur’an states: (49:13) “O mankind! We created you from a single (pair) of male and female, and made you into nations and tribes, that you may know (respect) each other. Verily the most honored of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous of you. Allah has full knowledge and is well acquainted (with all things)”.

The Charter’s 47 clauses protect human rights for all citizens, including equality, cooperation, freedom of conscience and freedom of religion. Clause 25 specifically states that Jews and pagan Arabs are entitled to practice their own faith without any restrictions: “The Jews of the Banu ‘Auf are one community with the Muslim believers, their freedmen and their persons, except those who behave unjustly and sinfully for they hurt but themselves, and their families.

(26-35) The same applies to the Jews of the Banu al-Najjar, Banu al-Harith, Banu Sai’ida, Banu Jusham, Banu al-Aus, Banu Tha’laba, and the Jafna, a clan of the Tha’laba and the Banu al-Shutayba. Loyalty is a protection against treachery. The freedmen of Tha’laba are as themselves. The close friends of the Jews are as themselves. So the Covenant of Medina was the first political document in history to establish religious freedom as a fundamental constitutional right.

The “Charter of Medina” created a new multi-tribal ummah/community soon after the Prophet’s arrival at Medina (Yathrib) in 622 CE. The term “constitution” is a misnomer. The treaty was more like the American Articles of Confederation that preceded the U.S. Constitution because it mainly dealt with tribal matters such as the organization and leadership of the participating tribal groups, warfare, the ransoming of captives, and war expenditure. Two recensions of the document (henceforth, “the treaty”) are found in Ibn Ishaq’s Biography of Muḥammad (sira) and Abu ʿUbayd’s Book of State Finance (Kitāb al-amwāl). Some argue the final document actually comprises several treaties concluded at different times.