Suppression And Silencing: The Attack On Asad Toor, Press Freedom and Media Laws In Pakistan – Analysis

By Institute of South Asian Studies

The recent attack on Pakistani journalist and vlogger Asad Ali Toor shocked audiences in Pakistan and abroad. The subsequent events which unfolded revealed that the systematic suppression of the press goes beyond acts of physical violence, harassment and intimidation. Indeed, more subtle and procedural means of coercion continue to play a role in muzzling journalists. While a recent law passed in Sindh offers some optimism, the prospects for protecting critical voices in the country more generally look grim.

By Imran Ahmed*

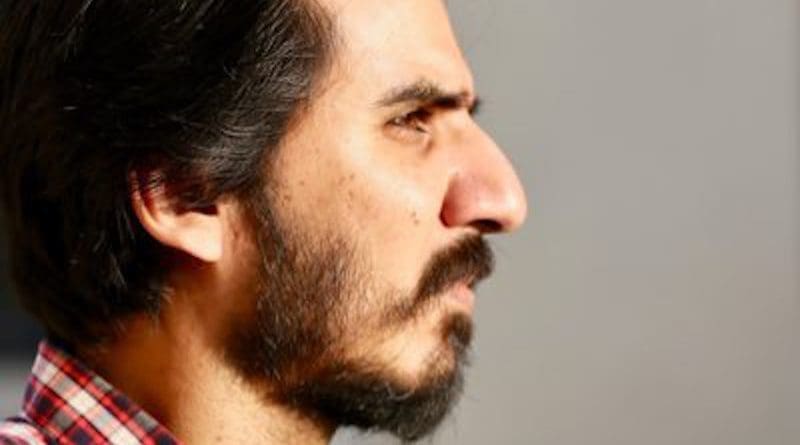

Asad Ali Toor, a journalist for Aaj News (Pakistani TV channel), was bound and beaten on the night of 25 May 2021 when three armed unidentified men forcibly entered his Islamabad residence. Toor, a vocal critic of the establishment (a euphemism for Pakistan’s powerful military and intelligence agencies), also operates a popular current affairs programme on YouTube titled Asad Toor Uncensored where his analyses of political developments in the country would be too sensitive or dangerous for mainstream media outlets to air. His channel, moreover, boasts over 33,000 subscribers. Toor was tortured and interrogated at gunpoint over the source of his funding. The encounter with the assailants left him seriously injured and he was rushed to a private hospital where his condition was determined to be stable. As CCTV footage of his attackers circulated across cyberspace, the assault was widely condemned forcing Interior Minister Sheikh Rashid Ahmed to launch an investigation into the incident. However, while the authorities promised a police inquiry, Toor accused the intelligence agencies in Pakistan for coordinating the attack. He maintained that the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the premier intelligence agency of Pakistan, was behind the intimidation – something the ISI attempted quickly to dispel.

The bold nature of the assault shocked audiences in Pakistan and abroad. But journalists across the country noted that the establishment’s suppression of the press has long been a systematic process of silencing critique where acts of physical violence, verbal harassment, abduction and intimidation are not just routine, – they are just the tip of the iceberg. Indeed, Pakistan ranks low in major global press freedom indices. Reporters Without Borders placed Pakistan 145 out of 180 countries in its 2021 World Press Freedom Index. The Index further declared that ‘impunity for crimes of violence against journalists is total’.

In its annual state of Pakistan Press Freedom 2021 report, the Freedom Network noted some 148 attacks on journalists between May 2020 and April 2021. And Islamabad, the report maintained, continues to be the most dangerous place in Pakistan for journalists. The International Federation of Journalists furthermore listed Pakistan in the five most dangerous countries for the practice of journalism in the world in its White Paper on Global Journalism. The report noted that 138 journalists were killed in Pakistan in the period 1990 to 2020.

While the numbers sketch a grim picture, other methods of coercion, manipulation and suppression complement the threat of physical or lethal violence. Outspoken journalists are frequently dismissed from mainstream networks as media outlets experience enormous pressure to toe the line in order to remain operational. This compels many to take to social media and the Internet to voice dissenting opinions. But this space also hosts new perils. The legal system itself operates as an instrument of harassment binding journalists lengthy and expensive judicial and court proceedings. In the aftermath of Toor’s allegations against the intelligence services, the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) issued a notice under Section 160 CrPC to summon him for ‘defamation of an institution of the Government of Pakistan through social media’. The notice however did not state which institution. Journalists critical of the establishment have alleged that the FIA functions as an instrument of harassment.

Moreover, media regulatory laws in Pakistan operate to smother dissent and insulate state institutions from criticism. The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016 (PECA) continues to be used to target anti-government content and silence journalists and activists. The FIA had previously charged Toor in 2020 for defaming the army under the PECA. The introduction of the Criminal Law Amendment Bill 2020 which renders intentional ridicule and defamation of the armed forces a punishable offence liable to imprisonment of up to two years, or a fine up to five hundred thousand rupees, or both, raised vociferous opposition. The Standing Committee on Law and Justice only recently approved the Bill. A more sinister proposal to establish a new media regulatory body through the proposed Pakistan Media Development Authority Ordinance has been denounced as “an unconstitutional and draconian law aimed against freedom of press and expression” in a joint statement issued by a coalition of media associations and journalism unions. For now, the proposed law remains a draft.

The establishment’s hold on the press has provoked opposition parties to speak out and discuss avenues to protect press freedoms. The passage of The Sindh Protection of Journalists and Other Media Practitioners Bill, 2021 offers some optimism. The trouble, of course, is that even if new laws are drawn up to offset the suppressive nature of old ones, it is not clear whether, or to what extent, they will be enforced.

About the author: Dr Imran Ahmed is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at [email protected]. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Source: This article was published by ISAS