Gantz’s Visit To India: Israel’s Hand In Building The Asian Leading Power – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Oshrit Birvadker

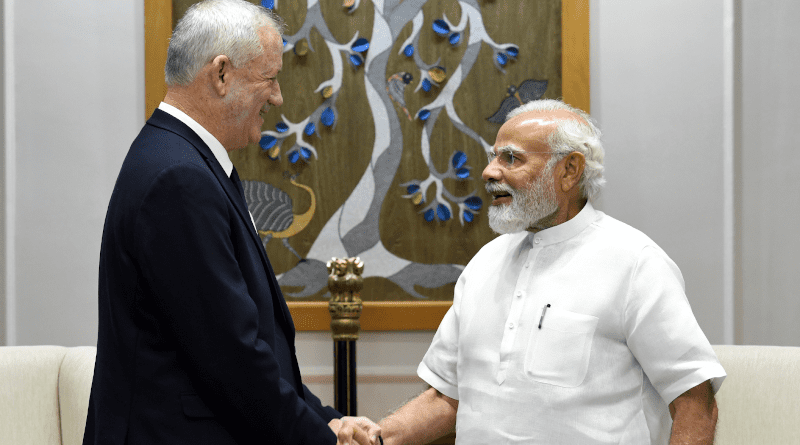

After putting off his visit to India in March, The Israeli Defence Minister, Benjamin Gantz, arrived in Delhi this past week, to sign a “security declaration” marking three decades of diplomatic ties between India and Israel. The visit is underway when Israel’s governing coalition is increasingly unstable after losing its majority in the Knesset and when there is a spike in terror attacks against Israeli civilians, indicating the importance that Jerusalem gives to the economic and strategic relations with India.

The defence relations between the countries form the basis for the current prosperous relations in economic, strategic, and cultural areas. Despite the Indian suspicion which characterised the first decades of the two post-colonial independent entities and despite the fact that New Delhi was sending aid to Israeli’s rivals during its wars with the neighbouring Arab states, Israel’s strategy was focused on diplomatic courtship and usage of its advanced military capabilities to prove its credibility as an ally worthy of India. The establishment of full diplomatic relations in 1992 was a founding milestone but it took many years to get rid of the Indian suspicion.

From the very beginning the Government of India had kept the military cooperation with Israel under the radar, but it was only a matter of time until it was exposed publicly, given the sheer potential it held for India. The former Minister of Defence, Sharad Pawar, noted in February 1992, that normalising relations with Jerusalem allowed the creation of an appropriate infrastructure to learn from Israel’s world-renowned experience in the field of counterterrorism and expressed Delhi’s main interest in R&D. A few months after the establishment of the full diplomatic relationship, the two countries made a significant leap in tightening military relations. A special delegation of Israeli defence personnel visited their counterparts in India. The details of the talks were kept a secret, but the visit symbolised the intentions of both parties to march on a joint path.

The late 1990s provided Israel with several opportunities to prove its commitment to India. During the downturn in India–United States (US) relations following the Pokhran nuclear tests that was carried out in 1998, the US sought to prevent the sale of advanced electronic systems to India by putting pressure on Israel. Despite the strong partnership that the US shares with Israel, Israel refused Washington’s request and supported Delhi while India was subject to US sanctions. Struggling in the international arena due to the sanctions, the victory in Kargil War in 1999, which was India’s first televised war, held multi-layered significance for Delhi. The defence experts argue that if the laser-guided missiles were not been delivered by Israel at that time, then ‘Operation Vijay’ probably would not have been successful.

Since then, technology transfer and licensed production have turned up to be the fundamental dimensions defining the strategic defence alliance between India and Israel. The scope of defense collaborations and acquisitions increased along with the tightening of relations during the Modi-BJP era. From 2014 onwards, Israel has become a significant player in India’s defence market alongside Russia and France. According to the SIPRI report, between 2015-2019, India’s arms imports from Israel increased by 175 percent.

Although the Modi regime created many opportunities for the Israeli market, at the same time it created many obstacles for the defence trade between the countries. Modi’s vision of ‘Atmanirbhar’ in the defence field alongside the ambition to make India the world’s largest factory under the flagship programme ‘Make in India’ has become a nightmare for decision-makers in the Israeli defence industries. Until now, the Israeli defence companies’ strategy such as Rafael focused on three major channels, each carrying an obstacle: The first is collaborating with local companies, which turned out to be very complex and not always suitable. The second is the establishment of local entity companies, which turned out to be problematic when the parentage of the company’s ownership came into question. The third, establishing a joint venture suitable to the field of the systems or products, which failed in meeting the criteria of available tenders.

Unfortunately, the governmental defence bodies such as SIBAT and the Administration for the Development of Weapons and Technological Infrastructure are still lacking the mechanism to adapt their strategies to the current reality in India. Expanding and deepening cooperation between the Israeli and Indian defence establishments must include the formation of a special committee for the ‘Make in India’ barriers. After all, the key to the further development of relations and maximising the potential lies in easing the activities of Israeli companies in India and the activities of Indian companies in Israel.

For years, Israel has sold arms to countries in the developing world to countries in Asia and Africa under the “follow the market” logic. For decades, India starred in this category. However, the country’s rapid growth rate over the past two decades and the great market potential have changed the prism through which many private companies look at India. In February 2020, even the office of the United States Trade Representatives (USTR) revised its list of developing and least developed countries and pulled India out from the list of countries that are categorised as developing. But today’s India has bigger ambitions.

India’s ambitions of becoming a leading power are mentioned in almost every public statement of the present government officials. To be worthy of the honour, Modi knows that it must strengthen its hard power capabilities. Therefore, Israeli companies can rest. The modernisation of the Indian defence industry has a long way to go. And as long as China continues to build its war abilities to provoke and threaten land and sea borders with India, the latter will proceed with its acquisitions of Israeli-made products such as UAVs, drones, and advanced missile systems. But one thing has changed—the Indians perception of themselves. India has become aware of its needs but also of its rising power and it is not willing to be in the place of just a buyer but in a place that exchanges ideas, fosters innovation, and require equal visibility in the negation table. For the Israelis, it takes time to grasp this change.

India’s importance has been reaffirmed in the face of geopolitical changes. On the one hand, the geoeconomics contestation between the US and China has been creating unpleasant incidents for Israel with Beijing, as Washington increased its pressure on the Israeli government to call off deals with Beijing in investments in strategic infrastructure, weaponry systems, and sensitive tech companies. On the other, the war in Ukraine emphasised the importance of weaning Delhi from the old Russian equipment. Furthermore, Abraham Accords and its nascent grouping—The Middle Eastern Quad—generate a priceless opportunity to deepen relations with India through the Arab-Mediterranean trade corridor. In light of the internal and external transitions, it’s time Israel starts perceiving its relations with India beyond a client-seller one. Jerusalem should see itself as a partner in building Asia’s next leading power.

[1] Sharad Pawar quoted in The Stateman, February 28, 1992.