Highly Educated Women No Longer Have Fewer Kids – Analysis

By VoxEU.org

Economists are increasingly interested in measuring the relationship between women’s work and education and the number of children they have – in part as a response to public policies that aim to empower women. This column assesses the evidence and finds that whereas in the 1990s highly educated women had fewer children than women with a lower education in the US, it is no longer true today.

By Moshe Hazan and Hosny Zoabi*

Highly educated women have always had fewer kids than women with a lower education (Jones and Tertilt 2008). Sociologists and economists have suggested many theories to explain this relationship. Leading explanations rely on the difficulty of combining children and a career (Mincer 1963, Galor and Weil 1996) and the quantity-quality tradeoff (Becker and Lewis 1973, Galor and Weil 2000, Hazan and Zoabi 2006). In today’s world, women have surpassed men in higher education in most developed countries (Goldin et al. 2006). What is more, women enter into more prestigious and demanding careers, and public policies reinforce this shift. For example, in 2012 the European Commission published a special report on women in decision-making positions, suggesting legislation to achieve balanced representation of women and men on company boards. Some countries – such as Norway, France, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands – have already taken legal measures in that direction. The shift in women’s education, coupled with more demanding careers for women, means that if the cross-sectional relationship between women’s education and fertility is stable over time, then future fertility rates will continue to decline from their already low levels.

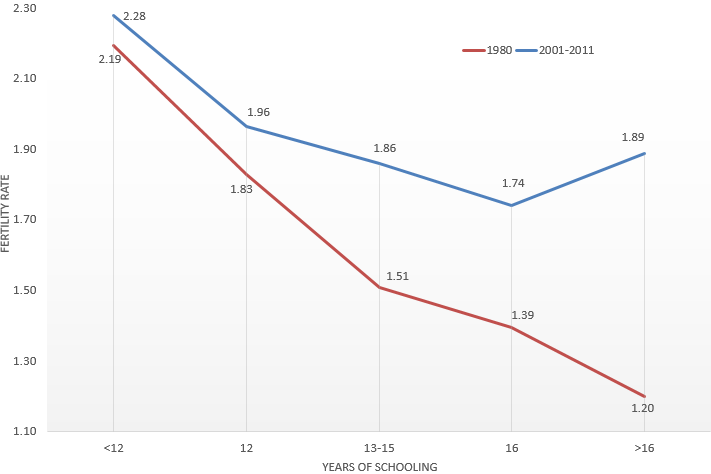

In a recent paper (Hazan and Zoabi 2015), we find, however, that while highly educated women had fewer kids than women with lesser education in the US until the 1990s, it is no longer true today. During the 2000s, highly educated women had higher fertility rates than women with intermediate levels of education. Importantly, this is a result of a substantial increase in fertility among women with advanced degrees who increased their fertility by 0.7 children, or by more than 50%. This is illustrated in Figure 1, which plots the cross-sectional relationship between fertility and women’s education in 1980 and during the period 2001-2011.

Figure 1. Fertility rates by women’s education, 1980 and the 2000s. What can explain the rise of fertility among highly educated women during the period that saw the largest increase in the labour supply of highly educated women? We argue that the growing income inequality over the past three decades created both a group of women who can afford to buy services that help them raise their children and run their homes, and a group who is willing to supply these services cheaply.

What can explain the rise of fertility among highly educated women during the period that saw the largest increase in the labour supply of highly educated women? We argue that the growing income inequality over the past three decades created both a group of women who can afford to buy services that help them raise their children and run their homes, and a group who is willing to supply these services cheaply.

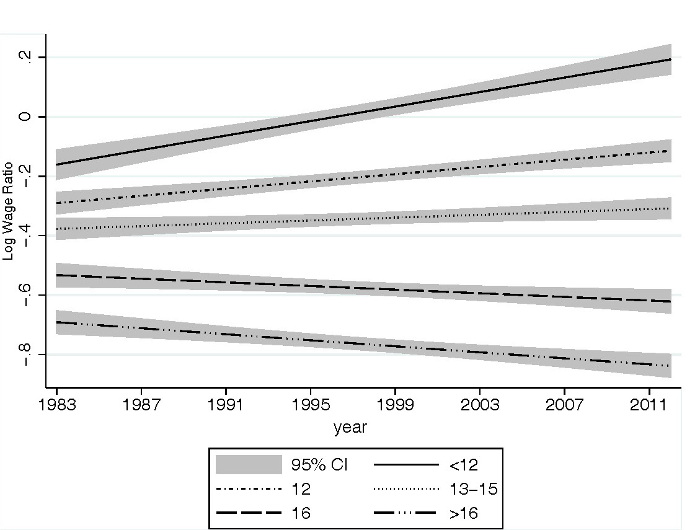

To study this, we use data from the March CPS for the period 1983-2012. We estimate the average hourly wage in the ‘child daycare services’ industry and allow it to vary by state and year. In addition, we compute the hourly wage of all women in the 25-50 year-old age group who reported a positive salary income. Figure 2 presents the fitted values of the average of this variable for each of our five educational groups. The figure shows that childcare has become relatively more expensive for women with less than a college degree but relatively cheaper for women with a college or an advanced degree. Note that the changes are quantitatively large. Over the past three decades, the relative childcare cost has increased by 33%, 16% and 5% for women with no high-school diploma, a high-school degree and some college education, respectively. In contrast, this relative cost decreased by 9% for women with a college degree and by nearly 16% for women with an advanced degree.

Figure 2. Linear prediction of the log of the ratio of average wage in the childcare industry to average wage in the five educational groups, 1983–2012 To utilise the micro data, we estimate regression models where the dependent variable is a binary variable that takes the value of one if a woman, living in a specific state in a specific year, gave birth during that year, and zero otherwise. Our main regressor is the labour cost in the child daycare industry divided by the own wage of that woman. We show that there is a highly statistically significant and economically large negative correlation between this measure of childcare cost and the probability of giving a birth. In our empirical analysis we find that this change in the relative cost can account for about one-third of the increase in the fertility of highly educated women. We use a battery of tests to show that this correlation is not driven by selection of women into the labour market, by the endogeneity of wages, or by specific years over the last three decades.

To utilise the micro data, we estimate regression models where the dependent variable is a binary variable that takes the value of one if a woman, living in a specific state in a specific year, gave birth during that year, and zero otherwise. Our main regressor is the labour cost in the child daycare industry divided by the own wage of that woman. We show that there is a highly statistically significant and economically large negative correlation between this measure of childcare cost and the probability of giving a birth. In our empirical analysis we find that this change in the relative cost can account for about one-third of the increase in the fertility of highly educated women. We use a battery of tests to show that this correlation is not driven by selection of women into the labour market, by the endogeneity of wages, or by specific years over the last three decades.

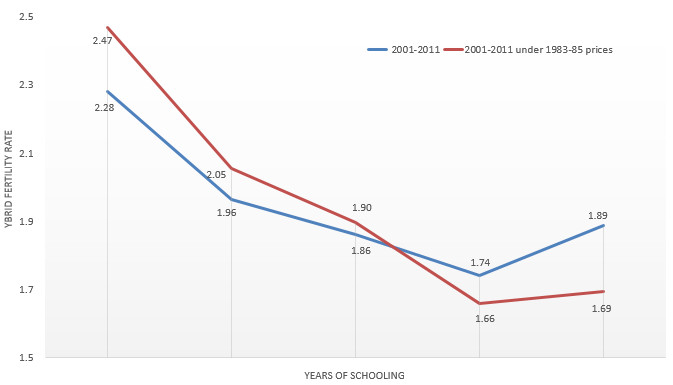

Figure 3. 2000s actual and hypothetical fertility under the 1980s prices of childcare Figure 3 uses the estimates from the regression models described above and shows a hypothetical fertility for 2001-2011 under the 1983-1985 relative childcare cost. The figure shows that the hypothetical fertility curve is obtained by a clockwise rotation of the actual fertility curve around the group of women that has some college education.

Figure 3 uses the estimates from the regression models described above and shows a hypothetical fertility for 2001-2011 under the 1983-1985 relative childcare cost. The figure shows that the hypothetical fertility curve is obtained by a clockwise rotation of the actual fertility curve around the group of women that has some college education.

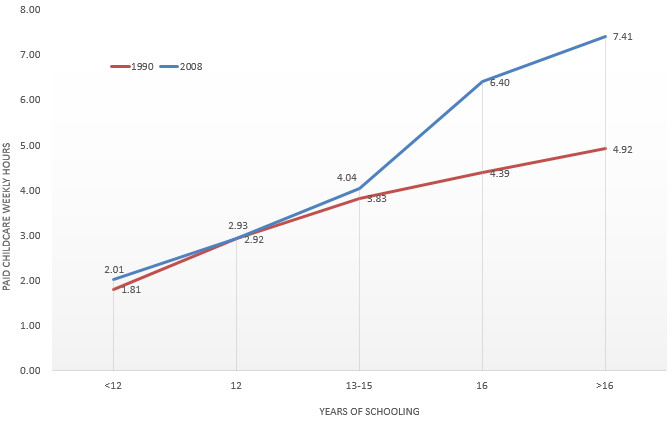

Direct evidence on paid childcare services is consistent with this view. Figure 4 shows the average weekly paid childcare hours by all women aged 25-50 in 1990 and 2008. The figure has two salient features. First, in each of these years, paid childcare increases with women’s education. Second, between 1990 and 2008, paid childcare hours have stagnated for women with some college education but have sharply increased for highly educated women.

Figure 4. Paid childcare weekly hours for women aged 25-50 We then rule out other potential explanations. First, we rule out substitution of women’s time between kids and market work. We show that hours worked are increasing in women’s education. However, since only a small fraction of women give birth in each year, it could be that women who gave birth in a given year do not work at all during that same year. To rule out this possibility, we show that hours worked are increasing in women’s education also among women who gave birth during the past year. Further, one might argue that the positive correlation between education and labour supply for women who gave birth during the past year might be driven by unmarried women, while among married women – the group that is responsible for the bulk of births – the opposite is true. Hence, we show that among women who gave birth during the past 12 months, the labour supply increases with education both for married and unmarried women.

We then rule out other potential explanations. First, we rule out substitution of women’s time between kids and market work. We show that hours worked are increasing in women’s education. However, since only a small fraction of women give birth in each year, it could be that women who gave birth in a given year do not work at all during that same year. To rule out this possibility, we show that hours worked are increasing in women’s education also among women who gave birth during the past year. Further, one might argue that the positive correlation between education and labour supply for women who gave birth during the past year might be driven by unmarried women, while among married women – the group that is responsible for the bulk of births – the opposite is true. Hence, we show that among women who gave birth during the past 12 months, the labour supply increases with education both for married and unmarried women.

A second explanation might be that marriage rates differ across different educational groups. If married women have higher fertility rates and if more educated women have higher marriage rates, more educated women’s higher fertility rates may not be caused by marketisation but rather simply by their higher marriage rates. We show that this is not the case because women with exactly college are more likely to be married than women with advanced degrees of all child-bearing ages.

Yet a third explanation might be related to the contribution of spouses to childcare. For example, partners of highly educated women might share more of the burden of raising kids compared to partners of less educated women. We show that partners of college graduate women spend only 30 minutes per week more with their kids compared to partners of women with lesser education, and that partners of women with advanced degrees spend less time with their kids compared to those married to women with exactly college degree, even though women with advanced degrees have higher fertility rates.

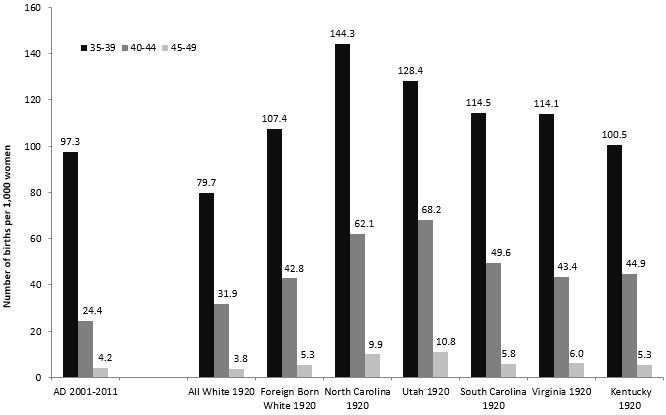

Figure 5. Number of births per 1,000 white women in the US in age groups 35-39, 40-44 and 45-49 – women with advanced degrees (2001-2011) and historical rates  A final potential explanation might be related to recent advancements in assisted reproductive technology that enable women to combine long years in school without sacrificing parenthood. We address this possibility in three ways:

A final potential explanation might be related to recent advancements in assisted reproductive technology that enable women to combine long years in school without sacrificing parenthood. We address this possibility in three ways:

- First, we show that historical levels of fertility rates among women above age 35 were higher than the levels during the 2000s (see Figure 5).

This stands in contrast to the argument that highly educated women were not able to have higher fertility rates in the past due to medical reasons.

- Second, we note that assisted reproductive technology accounts for less than 1% of births during the 2000s.

- Finally, 15 US states have infertility insurance laws that provide coverage to infertile individuals.

We compare fertility patterns by women’s education in these states to the rest of the country and find no difference in fertility rates during the 2000s.

Conclusions

The results of this study have several implications. For public policy, it highlights the potential benefits from pro-immigration policies. Unskilled immigrants can potentially have a positive effect on fertility via an increase in the supply of cheap home production substitutes. For many developed countries that are facing ageing and shrinking populations, this may be something to consider. It also has consequences for economic growth. Given the strong correlation between parents’ education and kids’ education, an increase in the relative representation of kids coming from highly educated families means that the next generation is going to be relatively more educated. This is good news for economic growth.

*About the authors:

Moshe Hazan, Senior Lecturer of Economics, Tel-Aviv University; Associate Editor, Macroeconomic Dynamics; Research Fellow, CEPR

Hosny Zoabi, Assistant Professor, The New Economic School, Moscow

References:

Becker, G S and G H Lewis (1973), “On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children”, Journal of Political Economy 81: S279–S288.

Galor, O and D N Weil (1996), “The gender gap, fertility, and growth”, American Economic Review 86(3): 374–387.

Galor, O and D N Weil (2000), “Population, technology, and growth: From Malthusian stagnation to the demographic transition and beyond”, American Economic Review 90(4): 806–828.

Goldin, C, L Katz, and I Kuziemko (2006), “The homecoming of American college women: A reversal of the college gender gap”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(4): 133–156.

Hazan, M and H Zoabi (2006), “Does longevity cause growth? A theoretical critique”, Journal of Economic Growth 11 (4): 363-376.

Hazan, M and H Zoabi (2015), “Do highly educated women choose smaller families?”, Economic Journal 125(587): 1191–1226.

Jones, L E and M Tertilt (2008), “An economic history of fertility in the U.S.: 1826-1960” in P Rupert (ed.) Frontiers of Family Economics, pp. 165 – 230, Emerald.

Mincer, J (1963), “Market prices, opportunity costs, and income effects” in C F Christ (ed.) Measurement in economics: Studies in mathematical economics and econometrics in memory of Yehuda Grunfeld, Stanford University Press, pp. 67-82.