How Indonesia’s Presidential Candidates Are Rebranding Themselves – Analysis

By BenarNews

By Ahmad Syamsudin

One presidential candidate dances vigorously despite his age, another flashes a three-finger Hollywood film salute to be hip with the masses, and a third hopeful posts pictures on Instagram of – what else – his cats.

In the race to determine who will be the next leader of Southeast Asia’s biggest country, the three candidates are using various tactics to grab attention on social media – all in an attempt to woo young Indonesian voters.

These contenders have crafted unique ways of campaigning as they attempt to rebrand themselves to reach Gen Z-ers and millennials, who make up more than half the electorate in the Feb. 14, 2024, national election.

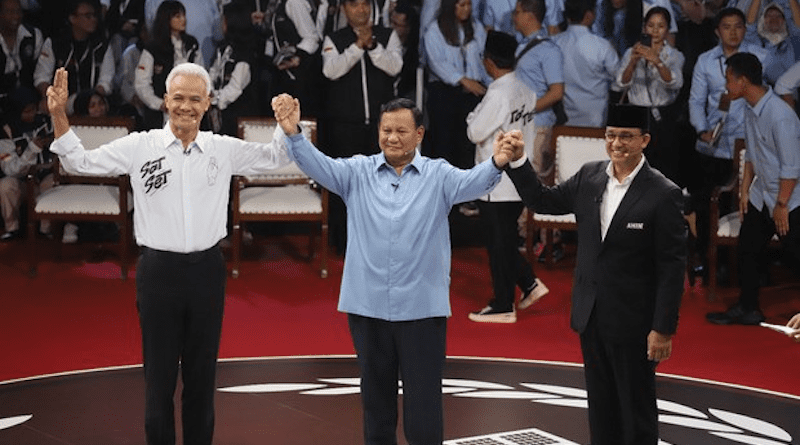

The presidential race features Prabowo Subianto, 72, a former army general with an allegedly dark past, a former Central Java governor, Ganjar Pranowo, 55, and Anies Baswedan, 54, an ex-governor of Jakarta.

As the world’s third-largest democracy goes to the polls to determine who will succeed two-term President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, some voters and observers have questioned what they see as the lack of substance and vision behind candidates’ slogans and gimmicks.

‘Cuddly’ ex-general

And yet, these tactics appear to have worked for Prabowo, who has become something of a social media darling.

Prabowo, who was accused of human rights violations during the Suharto dictatorship and the 1998 riots that led to the former president’s downfall, has skillfully crafted a social media persona who is playful and humorous, observers said.

His campaign, too, uses cartoon-avatars of Prabowo and his running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka depicting them as smiling, chubby-cheeked jolly folk who could be one’s neighbors.

Videos posted on social media showing Prabowo performing dances at various events have garnered millions of views and likes, earning him the nickname “gemoy,” meaning “cuddly” or “cute.”

And Gibran, the president’s eldest son and the mayor of Solo, who has been criticized as aloof and privileged, has sometimes joined in for a bit of a jig. On Sunday, he defended Prabowo’s antics.

“What’s wrong with dancing, what’s wrong with being happy?” he said in front of thousands of supporters and volunteers at a rally in Bogor, on Jakarta’s outskirts.

“Now I ask you, is it not allowed for people to be more joyful?”

Nina Andriana, a political communication expert at the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), said Prabowo’s strategy to rebrand himself seems to have worked, although his plans for the nation were fuzzy.

“The chubby [cuddly] image is catchy and attractive, and it works well with the social media algorithm,” Nina told BenarNews.

But he has “no clear political message or vision,” she added.

Azeza Ibrahim, a 35-year-old voter and office worker in Jakarta, agreed.

“Dancing is not enough to attract voters. The people want to hear their solutions for the economy, as the prices are going up,” he told BenarNews.

He also said that Prabowo and Gibran were not very interactive, despite their frequent public appearances.

“They dodged the debates held by universities and organizations,” he said, referring to their absence from some debates, although neither of them has taken leave from work to campaign.

Candidate Ganjar, though, is known for his down-to-earth and relatable charm. He often posts social media pictures and videos of himself running and cycling with ordinary Indonesians around the country.

To embellish his “man of the people” brand further, he has adopted a three-finger salute similar to the one used by the protagonists of the Hollywood film “The Hunger Games,” as a symbol of his campaign. In the popular dystopian film, the salute is used by the fictional rebels who fight a tyrannical regime.

Pangeran Siahaan, a spokesman for Ganjar’s campaign, deems the symbol appropriate for Ganjar.

“We think it’s fitting, especially since in the movie the three-finger salute is also a symbol of the people’s struggle,” he said.

And yet he has consistently trailed frontrunner Prabowo in surveys, because, according to Jakarta voter Azeza, Ganjar isn’t very charismatic.

“He is boring on TV,” he said.

Ganjar’s promises to improve Jokowi’s legacy were not enough, Azeza said.

“We want to hear his ideas and plans as a presidential candidate. He hasn’t shown that yet,” he said.

Ganjar’s man-of-the-people credentials have also been tarnished by his handling of two land conflicts that erupted in Central Java during his tenure as governor.

In both, Ganjar was accused of allying with corporations and ignoring the rights and interests of the local communities.

Meanwhile, Anies appears to have the most substance of the three candidates, at least based on his stump speeches.

He has promised to improve public services, create jobs, and change laws that restrict freedom of expression. And he has positioned himself as the champion of the people, especially the poor and the marginalized, and a proponent of free speech.

Anies has also launched a series of campaign events called “Desak Anies” (Press Anies), where he meets with young and educated voters across the country to discuss various topics and issues, and showcase his knowledge and charisma.

He, however, is seeking to shake off the impression that he is a polarizing figure, a reputation he got after he aligned himself with Muslim conservatives in the run-up to the hotly contested Jakarta gubernatorial election in 2017.

His rival back then, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, an Indonesian Chinese-Christian, was accused by hardline Muslims of blasphemy for citing a Quranic verse during the campaign, and was subsequently jailed for two years.

Since then, Anies has tried to emphasize his image as an inclusive leader.

He’s cited examples of the Jakarta administration introducing Christmas carols in public places and renovating churches and temples when he was governor. He has also enlisted several prominent ethnic Chinese on his campaign team.

To enhance his relatability and add some pizzazz to his campaign, Anies turned to Instagram and his four cats – Aslan, Lego, Oboy and Snowball – because who doesn’t love posts about kittens?

Anies’ cats together have their own Instagram account called “Pawswedan” – like his name Baswedan – and have amassed 23,0000 followers. The presidential aspirant posts pictures of his cats with humorous captions or “their” catty comments, among other things.

Recently, Anies set himself up to be swatted with a sarong, a garment usually worn in religious settings by Indonesians, by his running mate, Muhaimin Iskandar. It’s a playful custom among children at mosques.

The two posted the filmed exchange on Instagram, and Anies is seen grimacing, chuckling and saying: “Quite painful.”

Nina, the BRIN analyst, said that Anies’ political campaign reflected his personality and style.

“He is a skilled speaker and orator who can impress and persuade people with his words,” she said.

“He uses this as his weapon to win votes.”

Pizaro Gozali Idrus in Jakarta contributed to the report.