Responsibility Of The Muslim World On Israeli Actions In Gaza? – OpEd

By Ambassador Kazi Anwarul Masud

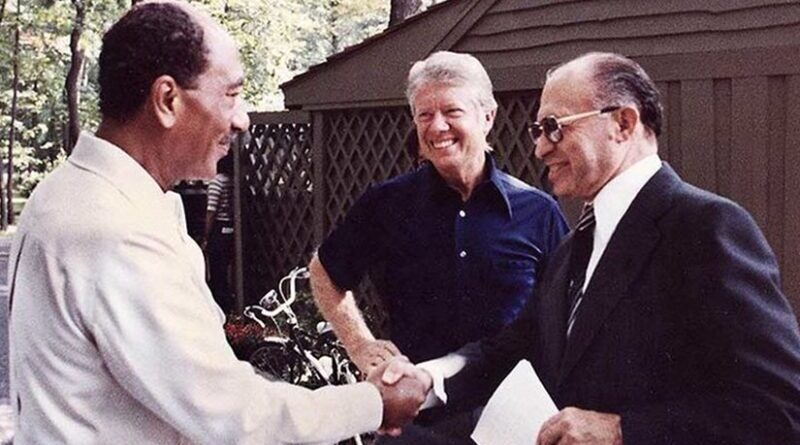

Does the Islamic World have any responsibility for the incessant and horrific injustice being committed by Israel towards the Palestinian people? Is it because Harry Truman not only recognized Israel as an independent country and as such gave cover to Israeli air space during the short war with Egypt when Anwar Sadat could have given a death blow to Israel but for the US cover of Israeli air space?

Laurence Rees, historian, and author, in his newest book published in March 2024 titled The Holocaust, wrote that “The fundamental precondition for the Holocaust happening was Adolf Hitler,” he explained that “Even as far back as 1921, Hitler said that solving the Jewish question was a central question for National Socialism. And you can only solve it by using brute force.” Hitler had no blueprint for the Holocaust at that point, says Rees. But he did have a pathological problem with Jews. “Hitler believed that something needed to be done,” Rees explains, “and that evolved and changed according to circumstances and political opportunism. “An intriguing part of Rees’s book is his determination to figure out when the collective set of initiatives we now call the Final Solution became official Nazi policy. It’s a question that doesn’t come with a straightforward answer,” Rees maintained.

What is clear, though, is that in the summer of 1940, there was still no concrete plan in place for the extermination of Jews. Furthermore, up until that point, Rees argued, the Nazis were still clinging to the belief that in the long term, the way to solve what they called “the Jewish question” was by expulsion and hard labor. At that point, mass murder was still not the preferred option. By the summer of 1942, however, a sea change had taken place. By that time, the Holocaust was in full swing. Therefore, within the previous two-year period, Rees points out, there were several milestones on the road towards mass extermination. But trying to pinpoint an exact moment where the decision was taken to commit to mass killing is very difficult, says Rees — especially since much of the planning was done in secret without written records. Hitherto, many historians, filmmakers, and writers have pointed to a single meeting where plans for the Holocaust were finally decided upon in the power structures of Nazi officialdom.

This was known as the Wannsee Conference. It was held in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee in January of 1942 and involved several mid-ranking Nazi officials devising a plot to murder Jews over a shorter timescale and in more efficient ways. But even then, Rees says, no final plans were resolved at the infamous conference. He also points out that key figures from the upper tiers of the Nazi hierarchy — Himmler, Goebbels, and Hitler himself — were not present. “I cannot see how there can have been a decision in 1941,” said Rees. “By that stage, you can say a decision to implement what we would now call the Holocaust had been The moment of no return for the Holocaust,” said the historian, was in the spring and early summer of 1942, when a decision was taken to kill all of the Jews in the General Government in Poland — a German-occupied zone established by Hitler after the joint invasion by the Germans and Soviets in 1939.“By that stage you can say a decision to implement what we would now call the Holocaust had been made,” said Rees. The Jews were transported to Auschwitz between May and July of 1944, where they were murdered.

Banality Of Evil?

This plan for cold-blooded murder was deviously orchestrated by Adolf Eichmann, who at the time was stationed in Budapest. What did Hannah Arendt mean by the banality of evil? a question asked by German-American historian and philosopher. Laurence Rees disagreed with Hannah Arendt though she continued to insist that one can do evil without being evil. This was the puzzling question that Arendt grappled with when she reported for The New Yorker in 1961 on the war crimes trial of Adolph Eichmann, the Nazi operative responsible for organizing the transportation of millions of Jews and others to various concentration camps in support of the Nazi’s Final Solution. Arendt found Eichmann was an ordinary, rather bland, bureaucrat, who in her words, was ‘neither perverted nor sadistic’, but ‘terrifyingly normal’. He acted without any motive other than to diligently advance his career in the Nazi bureaucracy. Eichmann was not an amoral monster, she concluded in her study of the case, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963). Instead, he performed evil deeds without evil intentions, a fact connected to his ‘thoughtlessness’, a disengagement from the reality of his evil acts. Eichmann ‘never realized what he was doing’ due to an ‘inability… to think from the standpoint of somebody else’. Lacking this particular cognitive ability, he ‘committed crimes under circumstances that made it well-nigh impossible for him to know or to feel that he was doing wrong’.

Arendt dubbed these collective characteristics of Eichmann ‘the banality of evil’: he was not inherently evil, but merely shallow and clueless, a ‘joiner’, in the words of one contemporary interpreter of Arendt’s thesis: he was a man who drifted into the Nazi Party, in search of purpose and direction, not out of deep ideological belief. In Arendt’s telling, Eichmann reminds us of the protagonist in Albert Camus’s novel The Stranger (1942), who randomly and casually kills a man, but then afterward feels no remorse. There was no particular intention or obvious evil motive: the deed just ‘happened’. This wasn’t Arendt’s first, somewhat superficial impression of Eichmann. Even 10 years after his trial in Israel, she wrote in 1971: “I was struck by the manifest shallowness in the doer. ie Eichmann, which made it impossible to trace the uncontestable evil of his deeds to any deeper level of roots or motives. The deeds were monstrous, but the doer – at least the very effective one now on trial – was quite ordinary, commonplace, and neither demonic nor monstrous.”

Critics Of Arendt

The banality-of-evil thesis was a flashpoint for controversy. To Arendt’s critics, it seemed inexplicable that Eichmann could have played a key role in the Nazi genocide yet had no evil intentions. Gershom Scholem, a fellow philosopher (and theologian), wrote to Arendt in 1963 that her banality-of-evil thesis was merely a slogan that ‘does not impress me, certainly, as the product of profound analysis’.

Mary McCarthy, a novelist and good friend of Arendt, voiced sheer incomprehension.

Conclusion

On October 6, 1981 Islamic extremists assassinated Anwar Sadat, the president of Egypt, as he reviewed troops on the anniversary of the Yom Kippur War. Sadat, who was shot four times, died two hours later. Despite Sadat’s incredible public service record for Egypt (he was instrumental in winning the nation its independence and democratizing it), his controversial peace negotiation with Israel in 1977-78, for which he and Menachem Begin won the Nobel Peace Prize, made him a target of extremists across the Middle East. Sadat had also angered many by allowing the ailing Shah of Iran to die in Egypt rather than be returned to Iran to stand trial for his crimes against the country.