UK’s Rwanda Bill: Stopping The Boats Or Setting A Precedent – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Shivani Pandey

The long-term implications of waves of mass migration spurred by decolonisation and globalisation are weighing heavy on the West. Immigration has emerged as a critical political, economic, and social issue in the West, serving as a substrate for the rise and proliferation of right-wing populist politics, with politicians often rallying popular domestic support by polarising the electorate.

While immigration has assumed a prominent position in electoral debates in the United States (US), Canadaannounced a 35-percent reduction in student visas for 2024. Australia aims to reduce its immigration by half by June 2025. In the United Kingdom (UK), Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has vowed to clamp down on immigration, beginning with his controversial Rwanda Asylum Plan and the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill.

Though international organisations, the Conservative and Labour parties have criticised the plan, PM Sunak government’s stern approach stems from immigration emerging as an increasingly contentious domestic political issue because of the ever-increasing influx of illegal migration. Regardless of the underlying motive, the UK’s Rwanda Plan raises questions about its desirability and impact on the international refugee protocol.

The Rwanda Plan

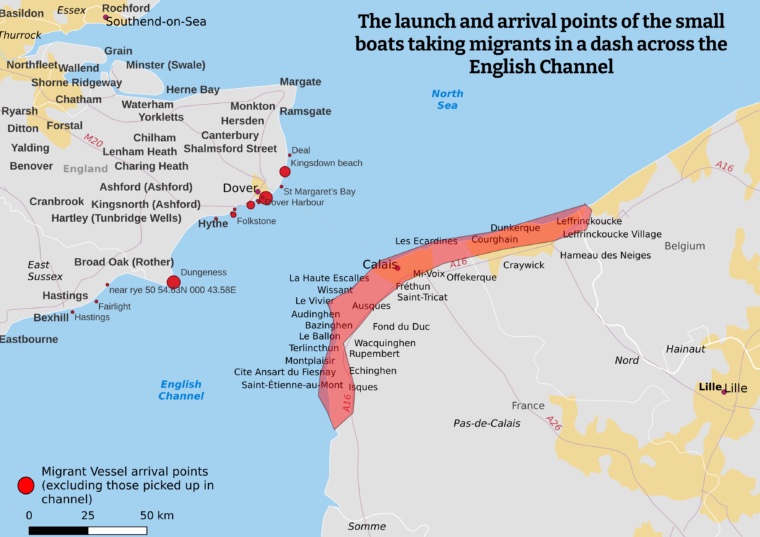

The former Prime Minister Boris Johnson proposed a five-year asylum agreement between the UK and Rwanda under the Migration and Economic Development Partnership (The Rwanda Plan) in 2022, seeking to address illegal immigration into the UK through unsafe and unauthorised routes. It aimed to curb irregular migration, specifically those happening via small boat arrivals across the English Channel (Figure 1.1). Such high-risk migration routes caused multiple fatalities and proliferated human smuggling mafias in the region. The plan sought to allow relocation of illegal entrants into the UK to Rwanda for immigration processing, asylum, and resettlement.

The plan prompted various human rights lawyers to challenge it in courts across the UK. The Supreme Court expressed concerns about the violation of the non-refoulement principle, which stipulates that asylum seekers “are not returned, directly or indirectly, to a country where their life or freedom would be threatened on account of their race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, or they would be at real risk of torture or degrading treatment”. Considering Rwanda’s substandard human rights record, it also questioned its credentials as a safe third country for the relocation of asylum seekers.

To circumvent the judgement, the Sunak government converted its anti-immigration “Stop the Boats” campaign into a legislative programme. It introduced The Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill, declaring Rwanda a safe third country for the relocation of refugees. The Bill won the first vote in the House of Lords in January 2024.

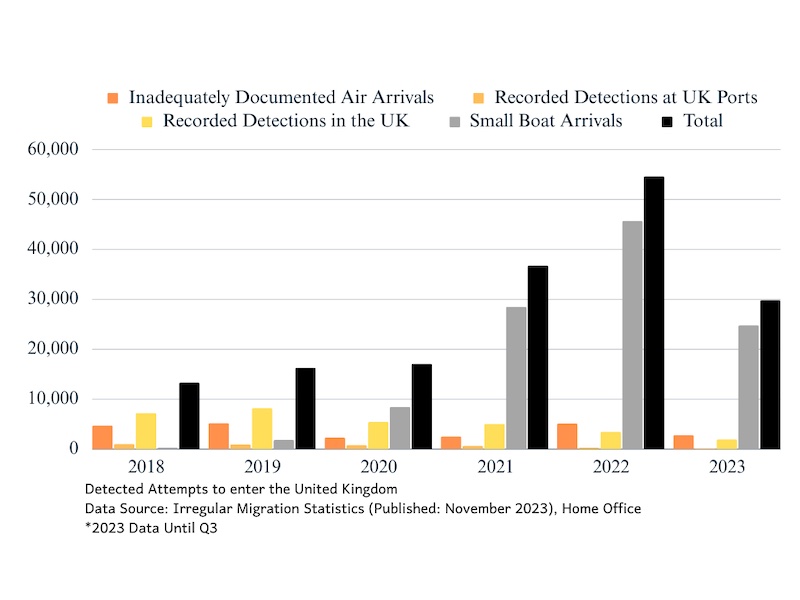

With thousands of small boat arrivals in the UK every year (Figure 1.2), the UK government has not stipulated the number of refugees it seeks to divert to Rwanda. While there is no cap defined, reports haveindicated Rwanda’s willingness to take 1,000 asylum seekers under the “pilot project” in the initial five years.

A weak attempt

Immigration is amongst the top three election issues in the UK’s domestic politics. As of 2020, 9.4 million foreign-born UK residents accounted for 14 percent of the country’s population. The Rwanda Plan seeks to address it by deterring irregular migrants. Interestingly, barring 2020, illegal migration as a percentage of total net migration has been below 10 percent (Table 1.1). Thus, the plan does not address the country’s broader migration crisis. With elections anticipated before January 2025, the plan serves as a popular rhetoric to portray the government’s hard stance on national security issues such as immigration, particularly in light of Sunak’s declining approval rating.

Table 1.1. Illegal Immigration as a Percentage of the UK’s Total Net Migration

| Year | Irregular Immigration | Total Net Migration | % of irregular to total immigration |

| 2018 | 13,377 | 276,000 | 4 |

| 2019 | 16,281 | 184,000 | 8 |

| 2020 | 17,100 | 93,000 | 18 |

| 2021 | 36,813 | 466,000 | 7 |

| 2022 | 54,702 | 745,000 | 7 |

Data Source: Irregular Immigration Statistics, UK Home Office; Long-term international migration, provisional: YE June 2012 to YE June 2023, Office of National Statistics

As a party to the UN Refugee Convention (1951) and its 1967 Protocol, the UK is obligated to provide asylum to any refugee at the risk of persecution, torture, or ill-treatment. The Rwanda Plan allows it to circumvent such binding international commitments. Asylum seekers from Iran, Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan, all countries in the grip of severe civil and political turmoil and violence, constitute 54.19 percent of the total illegal migrants. The plan thus deprives genuine refugees from seeking protections guaranteed under the international humanitarian laws.

Shadows of neocolonialism?

As of 8 December 8 2023, the Rwandan government has been paid £240 million as costs to accommodate the relocated refugees from the UK. It would get an additional £50 million in the financial year 2024-25. The UK has also agreed to aid Rwanda’s economic development. The Assistant High Commissioner for Protection, United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), expressed “dismay” at the plan’s “neocolonial” thinking.

Kwame Nkrumah, a neocolonial scholar, had decades ago likened such tactics as to giving power without responsibility to those who practised it. The UK’s Rwanda Plan exemplifies Kwame’s argument, as it helps developed countries like the UK to shed their duties and obligations under international laws and transfer the burden to a poor African country. Besides being a cash cow, the plan brings no other incentive to a least-developed country like Rwanda. It will export the domestic challenges caused by immigration from the UK to Rwanda while relieving the UK of economic, political, and security accountability.

Rwanda’s preparedness

Besides being silent on the number of immigrants to be exported to Rwanda, the plan raises questions regarding Rwanda’s preparedness to accept the multitudes seeking asylum. Does Rwanda have an unbiased asylum processing machinery? How will its conflict with Congo affect the incoming refugees? How will the refugees from Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Afghanistan affect the security landscape of Rwanda? Does Rwanda possess the socio-economic capability to educate, skill, and employ refugees to help them integrate into society?

An assessment of Rwanda’s development indicators tells a different story. With the second-highest population density in Africa, Rwanda has a high unemployment rate of 16.80 percent (the 12th-highest in Africa). It ranks 96 amongst 125 countries in the Global Hunger Index. Only 57 percent of the population has access to safe drinking water. Its GDP is ranked at 141 globally and 30th in Africa. Human Rights Watch highlights concerns about the lack of political freedom and incidents of torture in detention under the Rwandan government. There have been limited debates about the plan within Rwanda. Reports have suggested Rwandan people’s apprehensions over accepting refugees. However, due to restrictions on political and civil liberties, public outcry is limited for the fear of government repression.

These indicators question the UK’s choice of Rwanda as a destination to rehabilitate asylum seekers without considering the impact the plan may have on either the fate of the refugees or the effect on Rwanda’s economy and society.

An unhealthy global precedent

The Rwanda plan is a first of its kind that links economic partnership with refugee exportation. The strategy of developed countries to outsource their migration crisis to developing and poor countries in lieu of economic benefits will set an unhealthy precedent. The plan has already caught the fancy of several other European countries. Denmark, Germany, and Italy are considering similar measures to export asylum processing to a third-world country. Concerned by the long delay in implementation, the Rwandan President expressed concerns over the implementation of the plan. Sunak should take this opportunity to reassess the policy and pursue alternative solutions.

Migration being a humanitarian crisis, the international community needs a long-term strategy. The UK government’s deal with France, Italy, Türkiye, Albania, and others to control its borders is a positive development in immigration strategy. The UK government should also work with the European Commission, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and Interpol to eliminate the organised crime of human smuggling mafias. The European Union also needs to take charge of the continent-wide crisis fuelled by open borders by increasing regulation at its internal and external borders.

- About the author: Shivani Pandey is a Research Intern at the Observer Research Foundation

- Source: This article was published by Observer Research Foundation