Four Key Drivers For Eroding Islamic State – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Clint Watts*

Scary ISIS headlines have saturated media outlets in recent months. They usually come in three varieties: a) ISIS does incredibly awful thing(s) in Syria/Iraq, b) ISIS is unstoppable because of (fill in the blank), or c) the U.S. and the West must do (fill in the blank with every conceivable government option) to defeat ISIS. The international coalition seems unlikely to deploy overwhelming military force to rid the world of the latest awful jihadi group. All coalition partners are up for airstrikes, but no one seeks the dirty work of ridding Syria and Iraq of ISIS in direct military engagement. Likewise, at least in the West, there remains a complete lack of strategic consensus on what should be done to defeat ISIS.

A few months back, I offered up an alternative option to boots-on-the-ground; the “Let Them Rot” strategy–i.e., using containment to establish conditions by which ISIS destroys itself from within. (NB: A forthcoming paper will discuss this in greater depth.) To this point, it appears that the U.S.-led coalition, either by choice or more by default, is pursuing a modified “Let Them Rot” strategy. But officials and the public grow impatient while the media reinforces the belief ISIS is the next al Qaeda–a misguided one in my view. The headlines will lead you to believe that ISIS can only be defeated by a major military campaign. And counterinsurgency proponents are likely drooling for another opportunity to employ their beloved Field Manual 3-24. But defeating ISIS via external force will be a long battle, and one that perpetuates the jihadi belief that the West denies their vision. The U.S. should seek to destroy the idea of an Islamic State altogether, and to do that ISIS must fail by its own doings, not from outside forces. The recipe of the the “Let Them Rot” strategy should be followed: contain ISIS advances, starve them of resources, fracture their ranks, and exploit through alternative security arrangements.

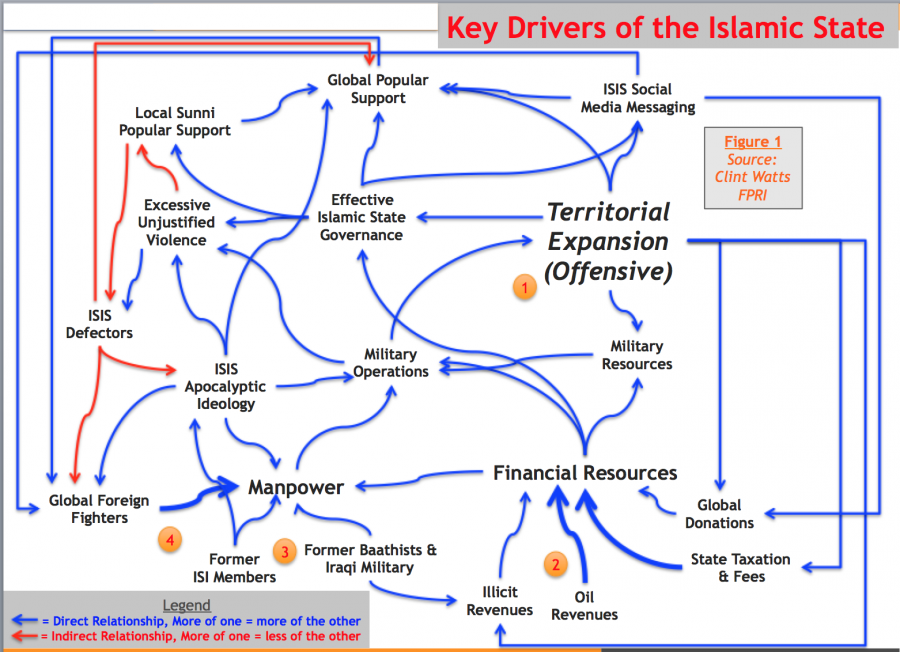

Analysis of the key drivers pushing forth the advance of ISIS reveals several key points at which the U.S.-led coalition can focus to degrade ISIS over time. Figure 1 below provides a causal flow diagram showing the relationship of key drivers powering ISIS operations. Note in the diagram that there are two relationships between entities. Blue arrows represent direct relationships where an increase in one factor leads to an increase in the subsequent factor. Red arrows represent where an increase in one factor leads to a decrease in a subsequent factor. (Bottom Line Up Front: Blue and Red show relationships, not good or bad, plusses or minuses.) In the diagram, clearly the most important factor is ISIS’s territorial expansion (see circle #1); their ability to sustain the offensive, and the initiative. The diagram also illustrates multiple feedback loops arising from their territorial expansion to include increases in their global popular support, financing through taxation and global donations, recruitment through social media, and their levels of military resources through the seizure of equipment. Containment of ISIS’s advance should remain the main effort, and I doubt that they can continue to expand much further.

Second, starving ISIS comes from disrupting one factor more than any other: elimination of oil revenues (see circle #2). ISIS, as compared to other jihadi groups that have tried to form emirates, developed the capacity to resource themselves years ago. Their self-resourcing is not only strong, but also diversified. Oil and taxation provide a dual-pronged financial power base complimented by global donations and illicit revenue schemes which have combined to buoy ISIS over time. Three of these financial resource streams, however, result in large part from ISIS’s ability to expand and sustain territory. If expansion was halted, these three streams would be constrained.

Starving ISIS of resources thus requires the elimination or degradation of ISIS capitalizing on oil fields in Eastern Syria. This will put pressure on ISIS to extract more revenues from the local population through taxation and illicit schemes preying on local populations at a time when expansion is no longer viable due to containment. The U.S. raid on Abu Sayyaf last month has apparently yielded some gains against ISIS and will hopefully be a first step in the elimination of this vital oil resource for ISIS. How does the U.S. disable the oil fields without destroying the infrastructure and creating an environmental disaster? Maybe a raid to facilitate a cyber attack, placing malware into the closed network to disable the oil pumping systems. Or maybe a series of raids to disable the equipment of several oil platforms, although this would be tough. Lastly, the coalition could send a militia deep into Eastern Syria to capture the oil fields, but in so doing will be anointing one group as king over all of the others.

Airstrikes, partner pressure, containment and starvation will ideally bring stress on ISIS disrupting the feedback loops previously created form territorial gains. Fearful of spies and infiltrators directing airstrikes and providing intelligence for Special Forces raids, ISIS will tighten its security, slowing their operations while further alienating the population. At the same time, ISIS will ideally become more predatory on the local population and increasingly self-doubting. At this point, two key fractures may become available for fracturing ISIS. First, in Iraq, internal starvation of resources paired with a slow and steady advance by Kurdish and Iraqi forces will hopefully incentivize former Baathists and Iraqi Sunnis to break ranks with ISIS to secure their local stake in Sunni territories of Western Iraq (see circle #3). A representative example of this dynamic was seen with the collapse of Shabaab from clan-oriented defections over the past three years.

The second important fracture for exploitation is the potential rift between ISIS Iraqi leadership and the global foreign fighter legions that power their ranks (see point #4). To date, young ISIS foreign fighters have had much to celebrate; winning on the battlefield, taking ground and rapidly becoming administrators of governance. But when battlefield advances end and resources become tight, local ISIS members will compromise their ideological principles to maintain their grip on power. Resource starvation, much as was seen in Somalia, will cause tensions between the heavily Iraqi-dominated leadership and the global ranks of foreign fighters.

Examining what is currently underway in the fight against ISIS, it appears that the U.S. is essentially pursuing this strategy. Despite the media ramping up the American public with a relentless barrage of scary ISIS stories, on the surface it appears the U.S., at least, is pursuing this strategy–they are doing most of what I just outlined. The trick will be whether they can exploit the fractures described above. Exploitation will be the hardest step, offering alternatives that fill the void and spread the rifts across Syria and Iraq.

About the author:

*Clint Watts is a Fox Fellow in FPRI’s Program on the Middle East as well as a Senior Fellow with its Program on National Security. He serves the President of Miburo Solutions, Inc. Wartts’ research focuses on analyzing transnational threat groups operating in local environments on a global scale. Before starting Miburo Solutions, he served as a U.S. Army infantry officer, a FBI Special Agent on a Joint Terrorism Task Force, and as the Executive Officer of the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC). His publications include: al Qaeda’s (Mis) Adventures in the Horn of Africa, Combating Terrorism Center, 2007 (Co-editor, Co-author); “Can the Anbar Strategy Work in Pakistan?” Small Wars Journal, 2007 ; “Beyond Iraq and Afghanistan: What Foreign Fighter Data Reveals About the Future of Terrorism?” Small Wars Journal, 2008; “Foreign Fighters: How are they being recruited?” Small Wars Journal, 2008; “Countering Terrorism from the Second Foreign Fighter Glut,” Small Wars Journal, 2009; and, “Capturing the Potential of Outlier Ideas in the Intelligence Community,” Studies in Intelligence – CIA, 2011.(Co-author). He is also the editor of the SelectedWisdom.com blog.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI