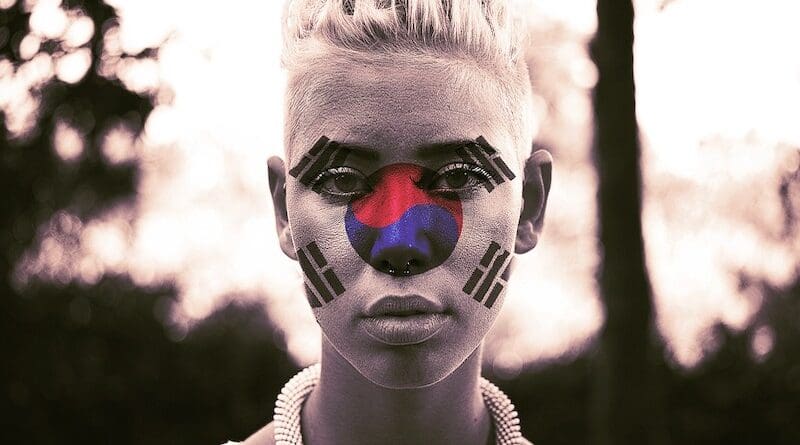

South Koreans Blame Feminism For Demographic Collapse – Analysis

By Dylan Motin

South Korea has the worst fertility rate in the world. Some link the country’s demographic collapse to the emergence of feminism, citing that it instils bitterness into the hearts of women, worsens gender relations and discourages young women from having children.

In public discourse, feminism and women’s rights advocacy are often associated with misandry and a hidden leftist or even pro-North Korean agenda of female supremacy. Given that there is little evidence that feminism is the source of South Korea’s demographic predicament, publicly focusing on this perceived issue may well divert South Korean policymakers from addressing the actual structural issues harming natality.

South Korea’s demographic crisis predates the rise of feminism as a widespread outlook and the 2017 MeToo movement. A country’s demography is considered sustainable when each woman has, on average, 2.1 children in her lifetime. South Korea’s total fertility rate (TFR) fell below 2.1 in 1983 and dropped down to 1.5 in 1998. This indicates that the natality crisis emerged during the rule of Chun Doo-hwan, hardly a time of feminist hegemony.

Contemporary South Korea is no feminist bulwark. It has the highest gender pay gap among OECD countries and some of the worst working conditions for women. The number of young women self-identifying as feminists decreased between 2021 and 2023.

South Korea’s demographic collapse, if unaddressed, could have serious repercussions. Even if Seoul could muddle through the economic and social repercussions, the resulting population decline would dramatically shift the regional balance of power.

South Korea still relies on conscription to maintain its military strength. The number of draftees, which represents around half of the force, could fall from 330,000 soldiers in 2020 to 240,000 by 2036 and 186,000 by 2039. Without radical changes, sustaining South Korea’s formidable military posture will become impossible.

As such, population decline represents an existential threat to South Korea. Its turbulent neighbour, North Korea, maintains around one million troops. China, Asia’s aspiring hegemon, has two million. China, North Korea and Russia all have nuclear weapons. An ageing and emptying South Korea would be an easy target for coercion. Pyongyang may even conclude that invading a crumbling South Korea to reunify the Korean Peninsula would be a cakewalk.

During the 2000s, the Russian government feared that its population’s low fertility would end its status as a great power and weaken its defence capabilities. It made the issue a national priority and managed to significantly reverse the trend. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, France had a stagnating population and faced a growing Germany. Here, too, efficient statecraft succeeded in redressing the country’s demography. It is important to note that in both cases, feminism had little to do with low natality.

Seoul should make its demography a national emergency and throw all its weight into finding solutions. Creating scapegoats for a multifaceted problem will not solve the issue. Instead, South Korea must acknowledge the underlying causes of its demographic crisis. The pressure to complete long degrees at university and then work long days with little rest makes raising children hard for young South Koreans.

Intense economic anxiety among the youth is another factor that delays births. Housing costs and household debt have risen significantly in recent years, further limiting the possibilities of forming a family. Dating and domestic violence also deter women from pursuing relationships. The social pressure of overinvesting time and money in children’s education further complicates the matter.

The traditional patriarchal model of the early-married, stay-at-home mother has deep roots in South Korean history and Confucian gender norms. But instead of clinging to an idealised version of bygone social relations, promoting a new one may help.

Childbirth outside of marriage is still frowned upon in South Korean society, yet the bar to marriage remains very high. This is because it is often associated with wealth, notably for buying a house. This creates a catch-22 whereby people envisage marriage only if they can afford a house, but affording a house is more challenging for unmarried than married people. Many are uninterested in marriage but still want to have children, yet suffering the condemnation of having a child ‘out of wedlock’ likely discourages them.

Decoupling marriage from childbirth would improve the situation. In 2022, only 2 per cent of births in South Korea occurred outside of marriage. The OECD average is around 40 per cent but above 60 per cent in France — one of the most fertile developed countries. Using the state’s public relations firepower to normalise extramarital birth and change its negative social perception could improve South Korea’s fertility markedly. Giving legal recognition to non-married families would also help.

This is just one approach to explore and the demographic crisis has many roots to treat. Yet it shows that low fertility does not come from the decline of traditions. Reimposing past gender relations and scapegoating feminism will not redress the situation. On the contrary, the dominant inflexible view of couples and childbirth is a part of the problem.

South Korea urgently requires a trans-partisan, whole-of-society effort to prevent its demographic extinction. It can only succeed if those in power offer policies based on a clear-eyed diagnosis of the crisis which looks beyond ideological divides.

- About the author: Dylan Motin is a Doctoral Candidate at Kangwon National University. He is also a researcher at the Centre for International and Strategic Studies and a Non-Resident Fellow at the European Centre for North Korean Studies.

- Source: This article was published by East Asia Forum