United Nations Issues: US Funding of UN Peacekeeping – Analysis

By CRS

By Luisa Blanchfield

The United States is the single largest financial contributor to United Nations (U.N.) peacekeeping activities. Congress authorizes and appropriates U.S. contributions, and it has an ongoing interest in ensuring such funding is used as efficiently and effectively as possible.

The United States, as a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council, plays a key role in establishing, renewing, and funding U.N. peacekeeping operations. For 2024, the United Nations assessed the U.S. share of U.N. peacekeeping at 26.94%; however, since 1994 Congress has capped the U.S. payment at 25% due to concerns that U.S. assessments are too high. Congress appropriated $1.37 billion to most U.N. peacekeeping activities for FY2024 (up to the 25% cap). Due to the gap between the U.N. assessment and the 25% cap, the United States has accumulated over $1.1 billion in arrears since FY2017. President Biden’s FY2025 budget request would fund the U.N. peacekeeping operations up to the 25% cap.

Overview of U.N. Peacekeeping

The United Nations currently operates 11 U.N. peacekeeping missions worldwide, with more than 70,000 military, police, and civilian personnel from over 100 countries. The Security Council adopts a resolution to establish each operation and specify how it will be funded. Historically, the Council has authorized the U.N. General Assembly to create a separate assessed account for each operation to be supported by member states’ contributions. In recent years, due to concerns about budget shortfalls, the General Assembly has pooled peacekeeping funding to allow for increased financial flexibility.

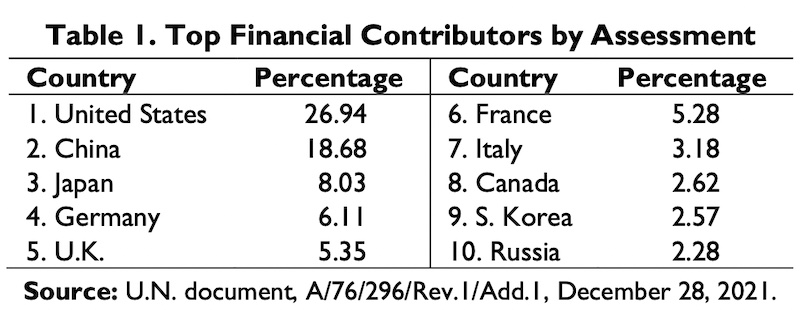

The General Assembly adopts the scale of assessments for U.N. member contributions to peacekeeping operations every three years. The peacekeeping scale is based on a modification of the U.N. regular budget scale, with the five permanent council members assessed at a higher level than for the regular budget. For example, the United States is assessed at 22% of the regular budget; however, its current peacekeeping assessment is 26.94%. Other top contributors include China, Japan, and Germany (Table 1). In December 2021, the General Assembly adopted the assessment rates for the 2022-2024 time period. Assessment rates for 2025- 2027 will likely be adopted in December 2024.

Some U.N. members, often referred to as troop contributing countries (TCCs), voluntarily provide military and police personnel for each mission. Peacekeepers are paid by their own governments, which are reimbursed by the United Nations at a standard rate determined by the General Assembly (about $1,428 per soldier per month).

The peacekeeping financial year runs from July 1 to June 30; the Assembly usually adopts resolutions to finance missions in late June. The approved budget for the 2023- 2024 peacekeeping fiscal year is $6.1 billion. Costs vary considerably among operations, with three of the missions in Africa constituting over 50% of the budget (UNMISS in South Sudan, MINUSCA in the Central African Republic, and MONUSCO in the Democratic Republic of Congo).

U.S. Policy

Background and Context: The Enacted U.S. Cap. In the early 1990s, the U.S. peacekeeping assessment was over 30%, which Congress found too high. In 1994, Members capped U.S. funding at 25% of the peacekeeping budget for all fiscal years after 1995 (Section 404 of P.L. 103-236). Over the years, the gap between the actual U.S. assessment and the cap led to funding shortfalls. The State Department and Congress often covered these by raising the cap for limited periods and/or by allowing the application of U.N. peacekeeping credits (excess U.N. funds from previous missions) to fund outstanding U.S. balances. For many years, these actions allowed the United States to pay its peacekeeping dues in full. However, since FY2017 Congress has declined to raise the cap, and in mid-2017, the Trump Administration allowed for the application of peacekeeping credits up to, but not beyond, the 25% cap— which has led to the accumulation of over $1.1 billion in U.S. arrears since FY2017. In early 2021, President Biden reversed the policy and allowed for the applications of peacekeeping credits beyond the cap.

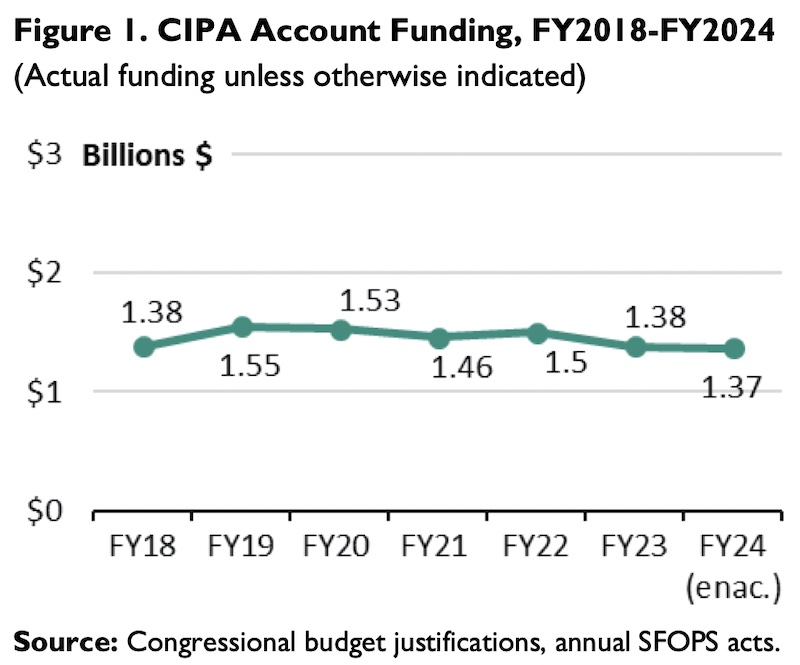

Key Accounts and Recent Funding Levels. U.S. assessed contributions to U.N. peacekeeping are provided mostly through the Contributions for International Peacekeeping Activities (CIPA) account, which is funded through annual State Department-Foreign Operations (SFOPS) Appropriations Acts. CIPA funds the majority of U.N. peacekeeping operations, as well as the U.N. criminal tribunals and mission monitoring activities.

In addition, the Contributions to International Organizations (CIO) account funds two observer missions, UNTSO (Israel and the Palestinians) and UNMOGIP (India and Pakistan), through U.S. funding to the U.N. regular budget. The Peacekeeping Operations account, which funds most non-U.N. peacekeeping and regional stability operations, provides assessed funding to the U.N. Support Office in Somalia, a U.N.-authorized logistics mission that supports the African Union Mission in Somalia.

The FY2024 SFOPS Act (Division F of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024; P.L. 118-47) provides $1.37 billion to the CIPA account (up to the enacted 25% cap) (Figure 1). President Biden’s FY2025 CIPA budget request is $1.23 billion (also up to the 25% cap). This represents a departure from the Administration’s FY2024 request, which would have fully funded U.S. peacekeeping assessments and included partial payment of U.S. arrears.

U.S. funding may fluctuate annually depending on several factors, including differences between the U.S. and U.N. peacekeeping fiscal years (the U.S. fiscal year is from October 1 to September 30, while the U.N. peacekeeping fiscal year is from July 1 to June 30), and discrepancies between the peacekeeping assessment and the enacted U.S. cap. Payments may also be affected by changes to assessment rates, the application of peacekeeping credits, and changes to individual operations. In some years, the timing of State Department reports to Congress (which are required by SFOPS acts) have delayed U.S. payments.

Selected Policy Issues

Funding and Growth of U.N. Peacekeeping. Debates over U.N. peacekeeping funding often occur against the backdrop of broader concerns regarding the changing nature of U.N. peacekeeping. The concept of peacekeeping has evolved since the first mission was established in 1948.“Traditional” peacekeeping involves implementing cease- fire or peace agreements; however, the Security Council has increasingly authorized operations in complex and insecure environments where there is little peace to keep and no clear outcome. Peacekeepers may be required to protect civilians, disarm violent groups, monitor human rights violations, or assist in delivering humanitarian assistance. Such activities can place additional financial demands on U.N. members. Some experts argue that current peacekeeping funding cannot effectively support some of the broad mandates authorized by the Council.

U.S. Peacekeeping Arrears. In the mid-1990s, the United States accumulated significant U.N. peacekeeping and U.N. regular budget arrears. Many U.S. policymakers were concerned that the United States could lose its vote in the General Assembly unless it made substantial payments on its outstanding dues. In 1999, Congress and the Administration negotiated what is known as the “Helms- Biden Agreement,” which established conditions under which some U.S. arrears, including peacekeeping arrears,

were paid. Since the enactment of Helms-Biden, some U.S. arrears remain. Arrears accumulated prior to 2001 for both open and closed peacekeeping operations total about $328 million. (Most of these are from the gap between the 25% U.S. cap and the U.N. assessment pre-2001, while others are the result of congressional policy holds.) As previously noted, the United States has also accumulated over $1.1 billion in additional cap-related arrears since FY2017. Some policymakers disagree about the status of peacekeeping arrears and argue that they should be paid, while others do not recognize them as arrears and claim the United States is under no obligation to pay them. Some have also raised concerns about the impact of U.S. arrears on the effectiveness of U.N. peacekeeping operations.

Sexual Abuse & Exploitation by U.N. Peacekeepers.

Congress has sought to link U.S. peacekeeping funding to the issue of sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by U.N. peacekeepers. For example, SFOPS Acts since FY2008 have prohibited the obligation of U.N. peacekeeping funding unless the Secretary of State certifies that the United Nations is implementing effective policies and procedures to prevent U.N. employees and peacekeeping troops from human trafficking or acts of illegal exploitation or other violations of human rights. Since FY2017, SFOPS bills have also prohibited assistance to any unit of the security forces of a foreign country if there is credible information that such unit has engaged in SEA until the Secretary of State certifies the country is taking steps to hold the unit accountable. The Department of State Authorities Act, FY2017 (P.L. 114-323) also requires reporting on U.N. efforts to hold perpetrators accountable for SEA prior to renewing or establishing a mission.

U.N. Peacekeeping Financial Situation. Some observers have expressed concern regarding the financial status of U.N. peacekeeping operations. In 2019, U.N. Secretary- General (SG) António Guterres noted an increase in the number of peacekeeping missions that were frequently cash constrained. Causes included payment patterns and arrears, and “structural weaknesses” in peacekeeping budget methodologies, including inefficient payment schedules and borrowing and funding restrictions. Such issues led to cash shortages and delays in reimbursements to some TCCs (U.N. document A/73/809). To address these issues, the General Assembly approved the management of cash balances of all active peacekeeping operations as a pool (while maintaining the balances in separate funds for each mission), and requested that the SG issue assessment letters for the full budget period approved by the Assembly (Resolution 73/307). U.N. officials report that due in part to these reforms, the overall liquidity of active peacekeeping operations continues to improve. The United States generally supported these efforts. Congress has demonstrated an interest in the effects of such funding shortfalls; for example, the FY2023 SFOPS Act required the State Department to report to Congress on overdue payments to TCCs, including any operational impacts.

- About the author: Luisa Blanchfield, Specialist in International Relations

- Source: This article was published by the Congressional Research Service (CRS).