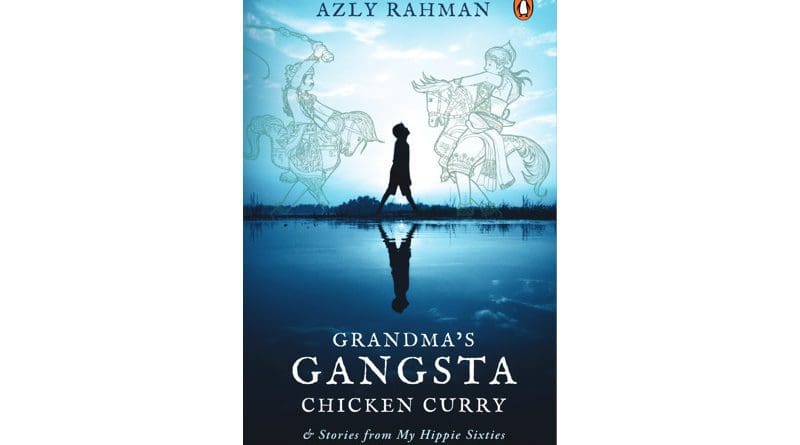

Grandma’s Gangsta Chicken Curry And Gangsta Stories From My Hippie Sixties – Book Review

Grandma’s gangsta chicken curry is a journey back to Azly Rahman’s time growing up in a Malay kampong, back in the 1960s and 70s. It’s a book of stories, poems, and narratives relating to times, people, events, and just the thoughts around some of his experiences, during adolescent years.

The book is a project of retrospective narratives, searching for meanings between the overlapping union of Azly’s conflicting influences. There is also a backdrop of the flux and transformation of a new nation Malaysia – Malaysia’s disconnect with the past colonial master, Britain, harmonious multiracial communities under pressure by race riots, the beginnings of harsh Islamic doctrine taking root in the country, the plague of drugs, and influence of American ideals of the 60s and 70s through film, television, and music. The narratives took place at a time when there was no electricity, running water, and no internet in the kampong.

Hence, existential awareness was more tactile then, than the technological cyberworld of the present. When you order KFC, customers don’t experience the slaughter of the chicken and effort to prepare the food, unlike in the Malay kampong, where the chicken must be chosen, caught, slaughtered, and prepared. There is much more meaning with the mundane in the kampong.

Azly points out that our perception is situational. How we view Ryan O’Neil and Mia Farrow kissing on the big screen depends upon whether we walked out of a madrasa, or saw the film after listening to rock and roll and smoking ganja.

It has taken Azly more than 50 years to take this reflective journey back in time. One can certainly very easily see that his mirrors of reflection are severely tainted with years in the United States. The reflective narrative gives new meanings to events, people, time, and places, altering greatly any sense of reality Azly had at the time, in the best traditions of Paul Ricoeur’s approach to narrative.

As the title of the book indicates, Azly has qualified his whole retrospective with the attachment of his “gangsta” persona. Gangsta is a heavily weighted Black and Latino-American slang word of the “Bronx, New York City and East Los Angeles, rap-hip-hop milieu” indicating not necessarily the road to self-destruction but of coolness and realization of self-recognition at a higher plane. Thus, Azly’s book is a retrospective phenomenological adventure, which has thrown away Margaret Mead’s book “Coming of Age in Samoa”, and turned its back on the ethnographical purity of Clifford Geertz. Instead, Azly has followed Ralph Ellison’s murky sojourn within “The Invisible Man”, trying to find the reality he is immersed within.

One of Azly’s major frames is the challenge of being Malay. As he describes the routine day, things are secular at school in the morning, full of Islamic rituals and dogma during the afternoons, and escaping into rock and roll in the evenings.

Azly is concerned with accepting superstition, the supernatural, the need to submit to authority, being accosted with pedophilia and homophilia, the demands of being born a Muslim, and the temptation of drugs, so easily available in the kampong.

As Azly says within the forward of the book, he is in a quandary. “I sit here writing about a cultural separation, I long for a union.” However, Azly admits that American influence is so pervasive, so additive. This concept of separation is holographic for him. Separation is not just concerned with his sense of identity, when growing up, but also externally with social and political events of the time.

What shows out through the book is that Azly’s American bias still cannot outweigh the Malay soul inside him. The product of this is anguish about the prejudices and injustices going on around him in this new post-colonial world, which still seems to exist with local Rajas and politicians, rather than colonial leaders. Azly metaphorically describes the dirty town of Johor Bahru, to the dirty politics of the country. He talks of all this being made to disappear by giving the streets beautiful names after aromatic flowers, so the mental images of dirt can disappear from public awareness, through metaphorical “whitewashing”.

Azly often looks deeply, introspectively throughout the book. For example, Azly draws a parallel between an execution and being circumcised in adolescence, as is the Malay custom. He ponders the pain and anguish thinking about the time it will take place and the pain that will occur. Suffering comes from the mind, thinking about an event which hasn’t happened yet.

At a spiritual level, Azly forms the hypothesis that pain is associated with learning to be a good person. This theme of shedding something, or separation, so that one can progress to a new understanding reoccurs a number of times. It’s a phenomenon that can occur within one’s own soul, culturally, or indeed nationally – sort of a theory of everything – concerned about change.

This is the brilliance of the book. It postulates there are a number of levels of meaning and reality to all phenomena. There is plenty of captivating descriptive narrative that brings you to where Azly is visualising. This is accompanied by a commentary occasionally, where Azly straight out, takes a stand.

Then there is the cultural level, examining rites and rituals, the beliefs, and assumptions behind them. This is how ghosts and the supernatural can be explained – not within the scientific paradigm, but within a cultural frame.

Then there is inner identity, very unstable and dialectical. Maybe this shouldn’t be analysed too much, other than modifying the old idiom that “you can take the Malay out of the Kampong, but you can’t take the Malay out of the person.”

In the end, it’s the narrative and accompanying semantics that makes up the identity, Azly has been on a sojourn for. We have to go back to the elephant within the room, the gangsta chicken curry. The meaning is all there for Azly. Metaphorically, the dish is as rich as the herbs and spices his grandmother put into the curry. That culinary association sticks, and will always be remembered no matter where, and at period of life a person is passing through.

One of Azly’s projected examples of meaning is – a simple one – the old illegal Mercedes diesel taxies in Malaysia in the 1960s and 70s, are still with us as Ubers today. Meaning just needs reframing.

Azly acknowledges that American culture has changed over time, hinting meaning has been lost, at least meaning for himself. He gives the analogy through music, pointing to the deep meaning of the lyrics in some of the old classic rock and roll songs, versus contemporary songs. Maybe, deeper is Azly’s romantic view of America in the 60s and 70s, and his mourning for what used to be, the loss of rock and roll philosophy.

Finally, one cannot overlook the political commentator frame that Azly is so well known for, particularly in Malaysia. Through snippets, Azly has given reasons why Malaysia is dominated by a Malay narrative and polity today. His messages about racism, corruption, religious extremism, and royalty, are there throughout the book.

For Azly, this book was an almost therapeutic retrospective sense-making perspective of his childhood. For the reader, it’s a valuable retrospective narrative about the personal challenges for a Malay youth in the kampong, back in the 1960s and 70s. In many ways indicating, challenges haven’t changed much for this generation, compared to the generations before them.

In general, the book also provides some window into how an ethnic American person reconciles their cultural origins within their American existence. This will be valuable in contemporary cultural studies.