UK Looks To India For Post-Brexit Trade Breakthrough – OpEd

By Andrew Hammond*

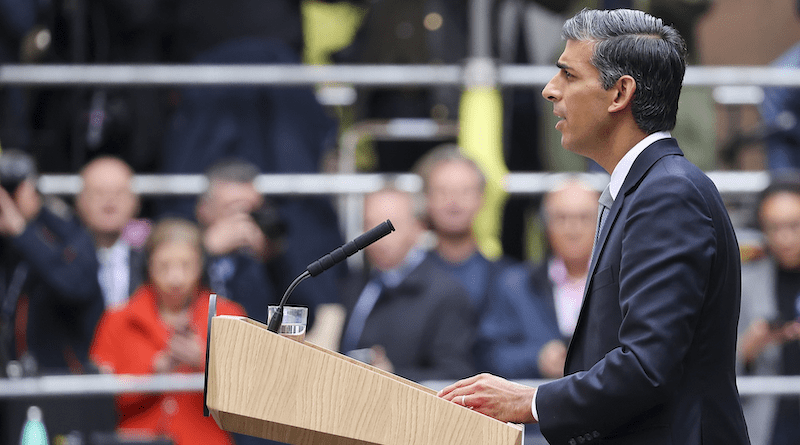

Much attention has been lavished since October on the fact that Rishi Sunak is the UK’s first nonwhite prime minister, having been born to Southeast Africa-born Hindu parents of Punjabi descent.

The symbolism of Sunak’s elevation represents an important moment in UK history and comes at a time when the government is hoping to close off a big trade deal with India. Secretary of State for International Trade Kemi Badenoch has been in New Delhi this week to try and advance negotiations, while Trade Policy Minister Greg Hands said in the House of Commons in October that a majority of the chapters on the agreement — 16 chapters across 26 policy areas — had already been agreed.

A bilateral trade deal, if negotiated properly, would be a huge prize for both London and New Delhi, which have unique ties dating back to the British Empire. This long relationship has been given new vitality by Sunak’s elevation to 10 Downing Street, with both of his grandfathers being born in the Punjab before emigrating to East Africa and then the UK in the 1960s. He is now part of the estimated 1.5 million-strong Indian diaspora population in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Both Sunak and his Indian counterpart Narendra Modi value bilateral ties. One signal of the importance the UK places on its relations with New Delhi was Foreign Secretary James Cleverly’s October visit to India to meet his Indian counterpart Subrahmanyam Jaishankar.

The UK, under Sunak, has at least two major reasons to put the relationship with India on as warm a footing as possible. First is the post-pandemic cooling of ties with China, which has been perhaps more significant between Beijing and London than with many other European capitals. This is, in part, because of the UK’s historical ties with Hong Kong, which it governed until handing over to Beijing’s control in 1997.

The second reason is London wanting UK firms, post-Brexit, to gain stronger access to the Indian market of about 1.3 billion consumers through a bilateral trade deal. The strength of the contemporary economic relationship is underlined by the fact that the UK is one of the biggest G20 employers and investors in the country. India, meanwhile, is one of the largest sources of foreign investment in the UK.

There are several elements of the economic relationship that have come to dominate bilateral ties recently and which Sunak wants to emphasize in a trade agreement. Firstly, he wants even stronger cooperation in defense manufacturing as part of a deeper bilateral security dialogue.

Second is further international investment, via the City of London, to finance Indian infrastructure. Third is technology, given the significant investment in Indian telecoms and tech firms by UK-headquartered businesses.

Yet, despite all the potential gains from a trade deal, there are challenges too. One key issue India is pressing for is UK immigration reform to enable more Indian businesspeople and students to travel to England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, as has been agreed in the UK’s post-Brexit trade deals with Australia and New Zealand.

While there have been some steps forward on this agenda — including an agreement in recent years between London and New Delhi on the swifter return of illegal Indian immigrants — there still has not been a decisive overall breakthrough. Moreover, controversial UK Home Secretary Suella Braverman inflamed ties last month when she said Indians were the nationals who most overstayed their UK visas.

Despite the remaining differences between India and the UK on the details of a new trade agreement, what is more striking is how much economics has come to dominate bilateral relations under Conservative governments since 2010. In so doing, some other long-standing issues have been de-emphasized, including human rights.

For instance, there was a debate in the House of Commons in 2018 in which MPs asked the government to raise with Modi, who leads the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, the treatment of Sikh and Christian minority groups in India. In 2013, there was even a House of Commons motion calling on the Home Office, which is responsible for the nation’s immigration policy, to reintroduce the previous UK travel ban on Modi, citing his alleged “role in the communal violence in 2002” in Gujarat. Under that ban, which was rescinded by London in 2012 before he became prime minister two years later, Modi was not allowed to enter the country due to his alleged involvement in those 2002 troubles, when he was the state’s chief minister.

Important as human rights are, these controversies will probably continue to be largely overridden by Sunak. As long as Sunak continues to prioritize UK-India ties under Modi, the two countries’ bilateral challenges will be superseded by the desire for greater economic collaboration.

- Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.