Mujib’s Legacy And Contemporary Bangladesh – OpEd

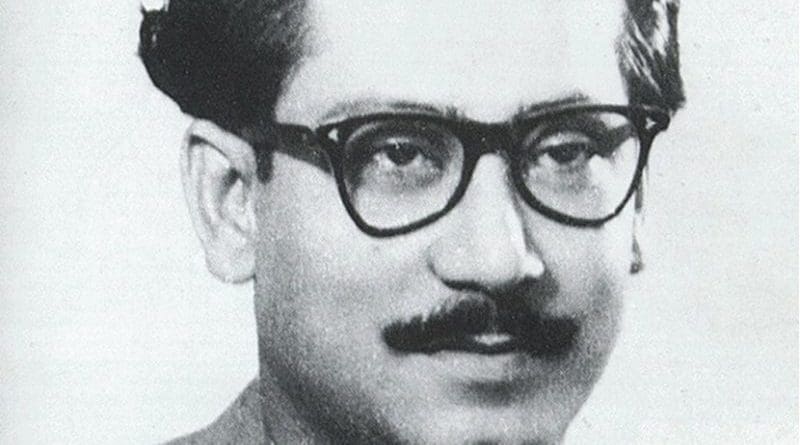

On his 104th birthday, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman who led Bangladesh to freedom will not only be remembered as Bangabandhu (Friend of Bengalis), but also as a role model liberator in the post-colonial world.

Considering that the creation of Bangladesh from the ruins of the failed experimental nation-state of Pakistan was the first successful secessionist struggle from a majoritarian post-colonial state in a post-imperial world, Mujib’s leadership model as the ultimate populist agitprop leader has and had many takers.

From the leaders of Papua New Guinea freedom struggle like Jacob Henri to the Kashmiri nationalists of the JKLF variety to the Tamil Tiger supremo Prabhakaran and not the least PLO founder Yasser Arafat, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was not only an inspiration but also a path breaker who evolved from a power-seeking electoral (sometimes street fighting) politician to a mass protest mobiliser with his trademark demagogy seeking autonomy and rights for the oppressed Bengalis in Pakistan’s eastern wing .

That he traversed this political escalator without much difficulty in the humdrum of Pakistani politics marked by military rule is a testimony to his political acumen and tactical (should we say survival) abilities not seen amongst the traditional middle class Bengali leaders.

Mujib was rooted in rural Bengal and his long years in Calcutta and Dhaka did not deprive him of his ability to connect to the grassroots. So much as he could evoke passion and romanticism for the Bengali cause, he was never carried away by the emotionalism of the self-sacrificing heroic Bengali revolutionaries who saw the gallows as the road to heaven.

He never took his eyes off the evolving power equations like Gavaskar never took his eyes off the rising ball — in the famous 7th Match 1971 speech that is seen as Bangladesh’s declaration of freedom, he begins by reminding Bengalis of the high cost paid in blood whenever we have tried to be ‘Maliks’ (owner) of our own place.

If Yayha Khan and Bhutto would accept him as Prime minister of Pakistan after the 1970 elections, he would not surely have opted for secession, though many of his hardline supporters has had enough of Pakistan.

The fact that the Bengalis were completely unprepared for armed struggle on the day of the Pakistani military crackdown (March 26, 1971) shows that the Awami League under Mujib was still a party of petition or protests and he was still hedging his bets on a fair solution within Pakistan. That he handed himself over to the Pakistani army without a fight (whatever the excuse) also indicates two possibilities — his unflinching hope on a possible last ditch compromise solution within Pakistan (inspite of declaring independence on March 7) or a reluctance to lead the inevitable armed struggle and leave it to his more militant leaders like Tajuddin, Qamruzzaman, Nazrul Islam and Mansur Ali when the push came to the shove. It was Mujib’s team rather he himself who shepherded the armed movement– and they died with him defending the cause.

His riposte to Ghaus Bux Bizenjo when lectured about the need for unified Pakistan (“I have been an ardent Muslim Leaguer, you were not, we made Pakistan, you didn’t”) is a classic reminder to those now propagating Mujib as a Kim Il Sun type personality cult fighting uncompromisingly for freedom.

Unlike Subhas Bose who would settle for nothing short of freedom and go to any extent to achieve it, Mujib was less romantic and ideologically motivated and more of a practical politician who would accept peace if shared power. The success of the Bengali armed struggle for freedom has much more to do with the passion and zeal for freedom cutting across the class divide amongst the Bengali people than Mujib’s ability as a revolutionary organiser. He was no Mao, Ho Chi Minh, Castro or Che and surely not Subhas Bose but he must be credited for inspiring the zeal for freedom among his people to a level that made them go for the ultimate sacrifice

He knew his people well — the classic character of oppressed East Bengali peasantry who would try hard for compromise but once provoked would fight to finish, unmindful of the costs.

In today’s Bangladesh with his Awami League now in the 16th continuous year in power, Mujib’s legacy of creating a secular democratic very Bengali country inspired by the glorious Bangla language and syncretic culture that promotes religious tolerance has been seriously compromised. Those who value the legacy of 1971 have been largely marginalised in the party and polity. Daughter Hasina, prime minister for four terms, three in a row, have often played footsie with a host of Islamist radical groups like Hifazat-e-Islam, Khilafat-e-Majlish and rabid fundamentalists like the Pir of Chormonai. She balances between India, China and the West for her political survival severely questioned by detractors for three successive controversial elections but in her party and administration, there is a near complete takeover by Pakistan type Islamists led by her all-powerful advisor (some say defacto PM) Salman F Rahman (whose Muslim Leaguer father had even suggested using Arabic script for Bangla language) who is pushing the commissioning of 560 Model Mosques Islamic Cultural Centres across Bangladesh’s 64 districts, aimed clearly at decimation of Bengal’s syncretic trans-religious culture held high by secular groups like Udichi or Chayanaut. The jatra and the jari gaans (musical soirees) are clearly on the wane, the ‘waz’ has taken over and some of its proponents are not merely virulent against minorities but also women who are not demonstratively Islamic. There is clearly a need for a strong gender rights movement, alongside those for minority rights and the persistent demand of the freedom fighters for a return of 1972 secular constitution.

If Mujib spearheaded the revolution and Zia the counter-revolution, Hasina is clearly surrendering the revolution. The rise of the Hindu right in neighbouring India and the undermining of India’s secular edifice may be sought as justification for what Hasina is doing, but for those Bangladeshis who value the ideals of 1971, it is still the “Unfinished Revolution” that Lawrence Lifschultz lamented about in his magnum opus by the same title.