India’s Strategy In Space Is Changing – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Dr. Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan

Half a century after humans first walked on the Moon, space is still as much about scientific discovery as it is about strategic competition.

As was the case during the Cold War, outer space is an arena of terrestrial geopolitics. We can see this in the increased impetus for competition in various achievements in outer space, such as Moon landings, Mars exploration and, more directly, in the creation of space forces in various countries – France being the latest to announce it intends to establish a space command to improve defence capabilities.

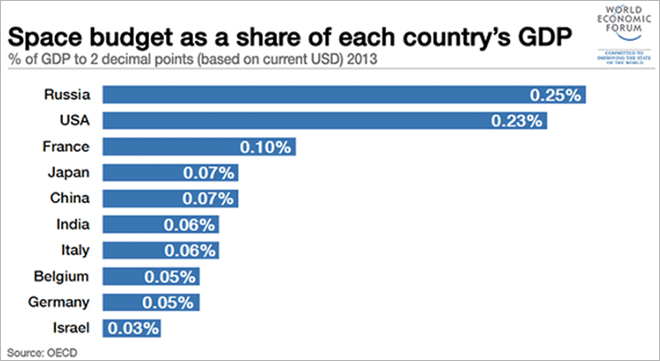

Yet, despite outer space being once again a field of power competition, there are also some differences from the Cold War years. First, and most significantly, there are many more countries and actors involved: in Asia itself, China, Japan and India are major spacefaring nations, and smaller players such as South Korea, Australia and Singapore are developing their own space programmes.

Added to the increase in countries is the entry of the private sector into space. A key difference in the new geopolitics of space is that both terrestrial competition – and its reflection in outer space – is now along multiple axes, rather than just the single U.S.-Soviet one.

Today, there is increasing power competition in Asia, particularly between China and its neighbours – India, Japan and Australia. Some of this is also reflected in outer space. As a corollary, we are also beginning to see greater cooperation between some countries in outer space, including India and Japan, both of which are concerned about the rise of China.

India also cooperates in space with the US, Russia and France. Much of the competition India has on land, on the other hand, is with China. Therefore, India has negligible cooperation with China in space, and equally, little competition with the other space actors.

A competitive chain reaction that (sometimes) reaches space

What occurs in space can be the result of a geopolitical chain reaction. For instance, consider the US-China-India relationship: China often takes action because of its strategic competition with the United States.

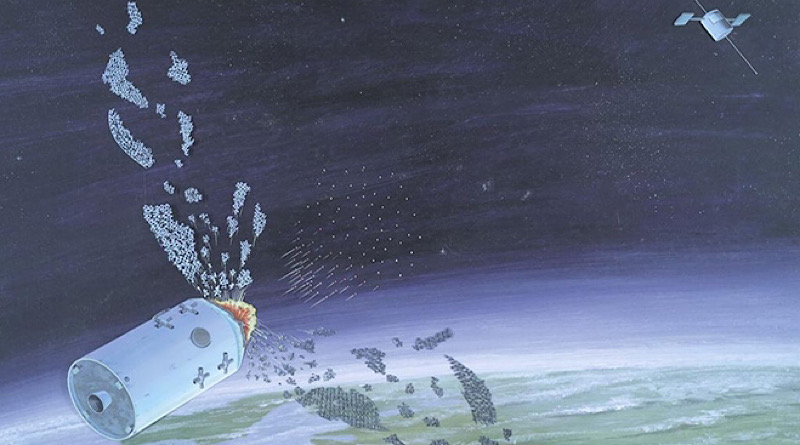

This has an impact on India, forcing India to respond. But India’s response to China has an effect on Pakistan, which then responds to India. This cascade can be seen on land, and at times, in space. For example, China’s first successful anti-satellite (ASAT) test in January 2007 was to demonstrate a catch-up effort with the United States. But once China tested its ASAT in 2007, India had little choice but to develop its own ASAT because of the need of deterrence.

But in the space arena, the competitive cascade does not travel all the way to Pakistan because Pakistan’s space programme is underdeveloped. While Pakistan has expended considerable national wealth in keeping pace with India in its nuclear and missile capabilities, it has not done so with regard to outer space.

On the other hand, there might be a security incentive for Pakistan to demonstrate that it also has an ASAT capability.

Pakistan could also develop other counterspace capabilities, including cyber and electronic means to target India’s space assets. While this remains speculative so far, the history of India-Pakistan competition suggests that this remains a possibility.

Evolution of strategy

India had long maintained a rather doctrinaire approach toward space security, emphasising the peaceful uses of outer space and opposing the weaponization and militarization of space. Thus, India had opposed the US Strategic Defense Initiative programme and other efforts to build ballistic missile defences, let alone deploying ASAT systems. The reasons for such an approach was fairly clear: India did not house these capabilities.

But by the early 2000s, India’s position had begun to change as Pakistan began acquiring long-range missiles. India felt the need to build ballistic missile defences, leading New Delhi to take a sympathetic view of the George W. Bush administration’s decision to withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty in late 2001. By the end of the decade, as India’s own capabilities increased, it was clear that India was becoming more discriminating in its attitude towards space security.

China’s ASAT test in 2007 helped advance India’s process of revaluating its space strategy. India realised that its growing investments in outer space – until then largely civilian in nature – were now under threat from China’s new security capabilities. India also started thinking more about how to manage outer space for security purposes. As a result, India established a space cell under its Integrated Defence Headquarters shortly after China’s ASAT test.

In April 2019, India established the Defence Space Agency (DSA) as an interim measure to command the military’s space capabilities. All of this meant that India had to have a much more nuanced position than a blanket approach that opposed any militarization or weaponization of outer space.

However, the consequences of unbridled militarization and the weaponization of outer space has negative implications for India. Therefore, while India is pursuing a strategy that satisfies its own security interests, it still wants some international control on the militarization and weaponization of outer space.

This article originally appeared in World Economic Forum.

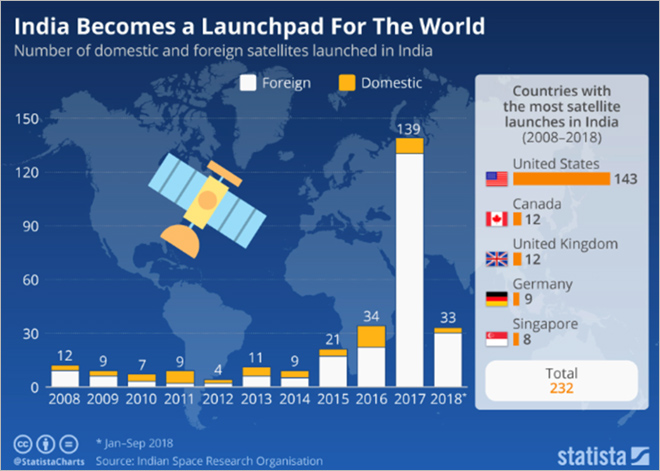

Very good article, but I have a few thoughts. Firstly I believe there is more to be said about the domestic impact of India’s space strategy. India’s space programme, ISRO, is a massive source of pride for the country and fueled both domestic political campaigns and international influence for over a decade. This has also had a positive impact on India’s image in the region and has enhanced its status as a regional power. The image of Indian space success is a bipartisan constant in electoral politics and is often leveraged to drum up support for other foreign policy advancements. I really think this is a phenomenon that is often overlooked & should be studied further.

Additionally, the flip side of space diplomacy is important to look at. While China and Pakistan are important neighbors, the US, being the largest spacefaring nation, should be examined in its relationship with India. Unfortunately, the US has historically been unable to tap into this well of Indian space pride. Its history of mistrust and secrecy stemming from the Cold-War era tainted Indo-American diplomacy, as NASA denied vital space technologies to India and launched spy satellites over the Indian Ocean without notifying ISRO. I still remember the backlash on the news afterwards. This definitely created a sense of mistrust in Indian space circles towards American space operations.

However, America’s new-age policy for space diplomacy, the Artemis Accords, could serve as a solution. Under the Accords, signatories share information about new missions, share crucial technologies, and strive to create a culture of cooperation and interoperability (Section 11 Article 5). Thus, bringing India into the Artemis fold could act as a hard reset to US relations with the world’s fastest growing economy and spacefaring nation. Perceptions of mistrust could be replaced with hope for greater cooperation. This would also allow for great US involvement in regional politics, as American diplomats could tap into the aforementioned domestic space pride to influence India’s decisions and thus wider geopolitics. So, while the escalatory aspects of Indian space progress is apparent in this article, it needs to go further in examining the domestic roots of space and potential for US collaboration.