When A Bridge Becomes A Wall: What Is The Language Of The Internet? – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Trisha Ray

The internet is not a great equaliser. The infrastructure gap is well-documented: the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) has quantified the “‘grand canyon’ separating the digitally empowered from the digitally excluded”. Despite double-digit growth in internet adoption in 2020–21, particularly in Asia and Africa, connectivity in the least developed countries stands at 27 percent. Of the 2.9 billion people without access to broadband internet, 96 percent live in the developing world.

Those from developing or least-developed countries who do come online must overcome a far more pernicious obstacle: language.

English remains the lingua franca, the bridge language, of the internet. Whilst only about 19 percent of the world speaks English as a first or second language, English accounts for 61 percent of content online. Even if we account for the fact that non-Anglophone populations may not be as connected as their English-speaking counterparts, the disparity is still stark: Approximately 26 percent of the internet’s users use English as their primary language.

| Most-Used Languages In The World by Number of Native Speakers(2022)* | Percentage of World Population | Most- Used Languages Online By Number of Users (2020) | Percentage of World Population | Top Content Languages (2022) | Percentage |

| 1. English | 18.82% | 1. English | 25.9% | 1. English | 61.2% |

| 2. Chinese | 13.80% | 2. Chinese | 19.4% | 2. Russian | 5.5% |

| 3. Hindi | 7.53% | 3. Spanish | 7.9% | 3. Spanish | 3.9% |

| 4. Spanish | 6.90% | 4. Arabic | 5.2% | 4. German | 3.2% |

| 5. French | 3.39% | 5. Portuguese | 3.7% | 5. Turkish | 3.2% |

| 6. Arabic | 3.39% | 6. Indonesian/ Malaysian | 4.3% | 6. French | 3.0% |

| 7. Bengali | 3.39% | 7. French | 3.3% | 7. Persian | 2.7% |

| 8. Russian | 3.26% | 8. Japanese | 2.6% | 8. Japanese | 2.6% |

| 9. Portuguese | 3.26% | 9. Russian | 2.5% | 9. Chinese | 1.7% |

| 10. Urdu | 2.89% | 10. German | 2.0% | 10. Vietnamese | 1.6% |

The language barrier goes deeper than the content. Only four widely-available coding languages are multilingual. Furthermore, in a vexatious turn, because English serves as the point of entry for most coders, even modern coding languages, such as Ruby or Lua, originating from non-English speaking countries use English terms.

A part of the problem is that the internet itself is a product of the English-speaking United States. So, whilst many hark back to a time when the Web was a self-governing community of like-minded people, free from politicking, the nostalgia is for an inherently exclusionary construct. As a 2019 Wired piece aptly states:

“The ‘initial promise of the web’ was only ever a promise to its English-speaking users, whether native English-speaking or with access to the kind of elite education that produces fluent second-language English speakers in non-English-dominant areas…The initial promise of the web is, for many people, more of a threat—speak English or get left out of the network.”

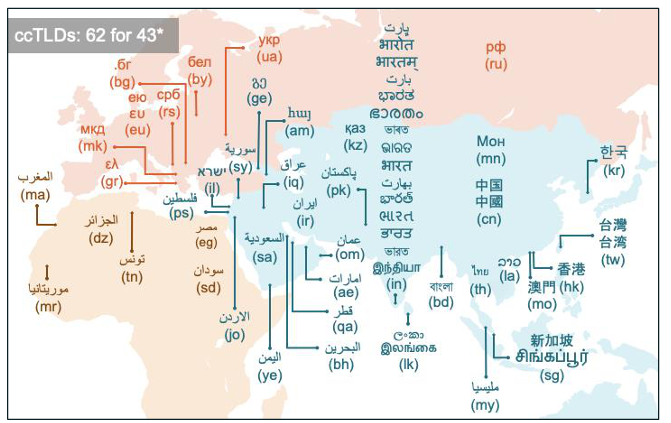

At a meeting of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN)[2]in Cairo more than two decades ago, participants pointed to the urgent need for non-English domain names. The first protocol for internationalised domain names (IDNs) was proposed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) in 2003. It was not until 2009 that ICANN began operational testing of IDNs, including kanji and hiragana (Japanese), hànzi (Chinese), and Arabic. By 2021, ICANN had delegated 62 strings from 43 countries and territories.

The lion’s share of the next billion internet users will not be from the developed English-speaking world, but their experience will be mediated through platforms that cater primarily to English speakers; their ability to tinker with the new concepts and services on the web will be limited to a handful of coding languages and they may struggle to find content that is in their native tongue.

Nonetheless, at a national and regional level, this dominance has shifted perceptibly over the past decade, driven in part by the proliferation of smartphones. Local alternatives to English-oriented platforms—such as the Kakao and Naver family of apps in South Korea, Grab in Southeast Asia, Taringa! in Argentina, Weibo and Tik Tok/Weixin in China, Moj in India—are surging in popularity, in some cases displacing global platforms in their home markets. Yet the baggage of lingua franca remains. Local apps are expected to cater to English speakers and are disparaged for not having large coding teams and user bases at par with, say, Google.

The building blocks of the World Wide Web have, and in many ways continue to, favour those who speak English. The status quo will, however, not always remain so.

[1] Calculations for number of native speakers (first and second language) as percentage of world population are the author’s own, based on population count as of January 1, 2022.

[2] ICANN is a non-profit multistakeholder group that deliberates standards for domain names.