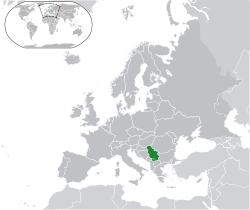

Facing Far Right Extremism In Serbia – Analysis

Reducing the threat of far right extremism – particularly its manifestation through terrorist means – involves finding a delicate balance between under-reacting and over-reacting; between giving tacit encouragement and sparking its escalation.

By Vladimir Ninkovic

Anders Behring Breivik reminded us once again that terrorism is an omnipresent threat that can strike in both rich and poor countries alike. A terrorist can be a man or woman, an engineer or a shepherd, a psychopath or mentally sane person. It is, therefore, very difficult to speak about the conditions and environments that facilitate the appearance of terrorism; whilst its erratic dynamics do not help us predict the time and place of the next terrorist attack.

Three years in a row, far-right organizations – together with the most conservative wing of the Serbian Orthodox Church and groups of football fans – have used threats of violence and de facto civil war to create a state of fear prior to the Pride Parade. In 2009 and 2011 they were successful enough to force the police and government to cancel the event at the last moment; whilst in 2010 – the only time it was held – the centre of Belgrade was wrecked by those who saw the Parade parade as an anti-Serb, anti-Orthodox and almost Satanic procession. Members of the LGBT and Roma communities, plus foreign citizens, have also been physically attacked several times in last few months.

Apart from football hooligans, the most prominent organizations which endorsed and participated in these events are generally understood to belong to the far right, such as the clerical-fascist ‘Obraz’, the chauvinist-nationalist ‘SNP Nasi 1389′ and the reactionary movement ‘Dveri’. Disconcertingly, such activities were de facto backed-up by the belligerent statements of certain politicians and church hierarchs.

Some definitions of terrorism describe it not only as the use of violence, but also as the threat to use violence in order to inculcate fear. The key point, on which almost everyone agrees, is that it is politically-motivated. The sources of ideology and the political aims of the terrorists, however, change almost every decade. Putting aside Islamic terrorism, the radical left (including Marxist-nationalist organizations, such as the IRA and ETA) were the dominant threat in Europe, and to a lesser degree in the USA, during the seventies and eighties, whilst the renaissance of the far right started somewhat later. The nineties were the golden years of the Patriot militias, Jean Marie Le Pen, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, Jorg Heider, including disasters such as the Riot of Rostock-Lichtenhagen in 1992, the Waco Siege in 1993 and the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 to name just a few.

It is generally regarded that the right-wing variant of terror is more likely to occur in, and pose a threat to, those societies that are going through a period of ‘transition’ and/or societies possessing, in the words of Wilhelm Heitmeyer, a “basic stock of equipment” in the form of conspiracy theories, a weapons scene, religious groups plying their views and social deprivation. Serbia shows signs of possessing each of these elements.

After decade of wars and poverty, the new millennium brought new challenges which Serbia’s democratically-elected governments have not always been successful in addressing. The proclamation of independence of Kosovo – and, to a lesser degree, Montenegro – caused feeling of bitterness and resentment towards the country’s continuing decay. The arrests of Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic, meanwhile, were negatively perceived by many citizens. The recent global economic crisis, high unemployment, perceived corruption in the public sector, crises in Kosovo and Sandzak and several other problems that Serbia today faces has contributed to deeply undermining trust in the government, in particular, and democracy, in general.

Such a situation, on the other hand, has benefited extreme right organizations who see opportunities amidst the end of the “democracy honeymoon” and the renewed quest for alternative solutions. Therefore, it should come as little surprise that the results of a recent survey conducted by the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights, entitled the “Attitudes and value orientations of high school students in Serbia”, showed that Serbian teenagers are significantly more conservative, nationalistic and xenophobic than the previous generations. Furthermore, the clerical, reactionary and anti-western “Dveri” movement announced participation at the next year’s elections.

On the basis of this, should Serbia expect to experience further radicalization and perhaps even terrorist attacks? According to some definitions, creating a state of fear and uncertainty can already be regarded as terrorism. In that sense, therefore, right wing extremists can already be deemed to have crossed the fine line between activism and terrorism. Apart from those seen as “outsiders” (such as foreigners, ethnic and religious minorities, leftists, civil rights activists and the LGBT community) the state itself – which is seen as ineffective and even under the actual control of the outsiders – could be attacked.

At first, terrorists usually avoid confrontations with the authorities, with their anger instead being directed at the outsider. Eventually, however, they convince themselves that the government is not doing enough to protect the “original community” and the state therefore also becomes a target. This is already apparent on several occasions, such as the attack on the USA embassy in February 2008, and the targeting of the B92 TV studio and the offices of the Democrat and Socialist Parties (the DS and SPS, respectively) during riots in 2010.

It is important to stress that both underreaction and overreaction by the state may trigger the process of radicalization. Underreaction – which has generally been the case in Serbia – can imply encouragement; whilst excessive repression may escalate into anger and hatred, and also give additional prominence to the extreme movements. The appeal of the fascist Russian National Unity in Moscow, for instance, gained prominence amongst youth after its gatherings were banned by Moscow’s mayor, Yuri Luzhkov. The political representation of far-right sentiments – through, for instance, Dveri, which demonstrates lesser tolerance towards other more extreme and less formal groups – could prove a mitigating force to the already present threat of further radicalization of an already quite popular far right. Finding a balance between overreacting and underreacting to the far right threat will be the task for not only government and its agencies, but also for the media and the civil society.

Vladimir Ninković is a project officer (security) for TransConflict Serbia. This article is published as part of TransConflict’s new launched initiative, Understanding Extremism, further information about which is available by clicking here.