Russia’s World Cup

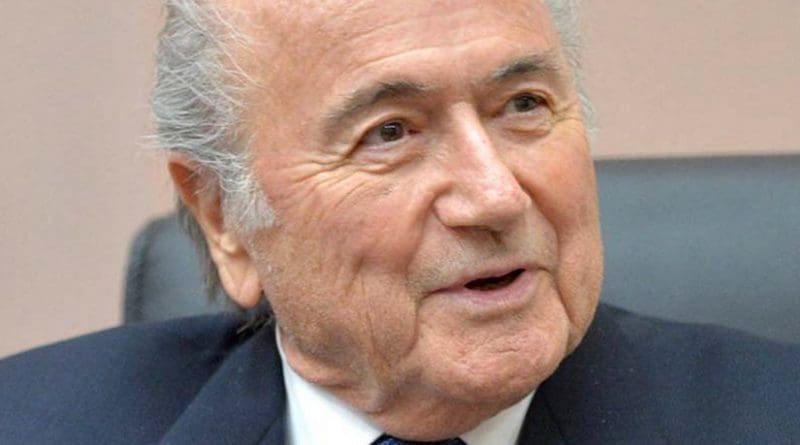

The anticipation was palpable, and FIFA president Sepp Blatter was keen to deliver. On December 2, Blatter announced that the recipients of the 2018 and 2022 World Cups, per a secret voting process involving a tiny 22-man cadre of FIFA insiders, were to be awarded to Russia and Qatar, beating out the heavily favored (and supposedly technically superior) England and USA bids.

FIFA’s reputation as a hopelessly corrupt organization is well known, and the global association football body did nothing to dispel those views with the surprise wins by bidding countries that were roundly regarded as having weaker proposals. [1] But the charges of institutional shenanigans, perhaps most eloquently summed up by soccer writer Bill Archer in a cynical — and prescient — May piece [2], is only one part of the equation. Blatter and FIFA are also searching for a legacy. Spreading the gospel of football around the world is a major component of that.

”You cannot deny Russia if they bid for something. They are more than a country,” said Blatter to the media over this past summer when asked about Russia’s chances. “They are a big continent, a big power.”

Or, as Archer more bluntly puts it back in May: “Sepp [Blatter] is determined to span the globe with World Cups, boldly going where no man has gone before, and if he can do that from a ‘personal legacy’ standpoint and still a) satisfy Europe and b) find a place where nobody will care about the graft, theft, bribery and general underhandedness, count him in.”

So, that’s one thing that joins the Russia and Qatar proposals — both distant outposts sitting on major geopolitical real estate (Russia and Qatar for the Arab, Muslim Middle East) that have yet to see a World Cup on their soil. What else do these two otherwise very different countries have in common? How about energy?

Russia’s vast energy reserves, as are Qatar’s, are both well known. More importantly, is that both of the resource-rich countries are well-placed by global demand to continue their economic expansion, meaning that their autocratic sovereigns are flush with cash that they can use at whim. That is not nothing.

For Qatar, the awarding of the 2022 World Cup is a major event, as the tiny sheikdom has never put together any kind of comparable party in its history. The country of 1.7 million will have its hands full pulling off its promises of air conditioned stadiums, underground practice facilities, and the like, but it at least has a humming energy economy to finance it.

For Russia, the situation is a quite a bit different. Unlike Qatar, Russia is no stranger to hosting major athletic competitions. In fact, Russia will be hosting one just four years prior to the 2018 World Cup — the 2014 Winter Olympics are set to be based in the Black Sea resort city of Sochi, incidentally only a short drive away from Abkhazia, which remains internationally recognized as a part of Georgia.

In early 2010, the Jamestown Foundation released an analysis on its blog on the significance of the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics.

“The Russian leadership considers the Sochi Olympics as a manifestation of Russia’s pride and growing great power status,” notes the piece, and adds that Russia “attaches ‘state significance’ to the due preparation for the Olympics.” The piece goes on to list the extent of some of those preparations and the fallout that it is causing for the region. [3]

And just as Sochi 2014 holds political significance for Moscow, there is no doubt that the even more high profile World Cup will, too. Will Russian policies change, or adjust, after the news of getting the World Cup?

Just as Sochi 2014 holds political significance for Moscow, there is no doubt that the even more high profile World Cup will, too.

The most immediate thought is no, Russia does what it wants with little concern for the outcome of interesting, but mostly inconsequential, athletic competitions like the World Cup, however high profile they might be. Russia will not adjust its foreign policy or change in its pursuit of national interests because of a sporting event, or even two.

This view has merit if one considers national interests to be narrowly defined as concrete goals and attainable objectives to be reached. However, the realities of statecraft tell us — as do the globs of Wikileaks cables — that obtaining the granular detail of what constitutes ‘national interests’ is difficult even during the clearest of circumstances. This is no less true for Russia, who may see the hosting of such events as a national interest itself rather than in the pursuit of something else.

Russia is keenly cognizant of how it is viewed in the world and has gained a historic reputation for a fierce inferiority complex that it perpetually seeks to assuage. And like the Sochi Olympics, the World Cup is an opportunity for Russia to get primetime billing to audiences globally to give its side of the story. Not unlike China, who carefully managed and calibrated their hosting of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, Russia will be keen to get this right to ‘finally’ prove its stuff.

For many in Eastern Europe who may see Russia’s hosting of the 2014 Winter Olympics as a moral affront, the awarding of the 2018 World Cup is unlikely to make matters any easier. Russia, goes the narrative, has hardly shown itself to be deserving of such an honor given the kind of actions it has undertaken in recent years. Indeed, Russia invaded a neighboring sovereign country only two years ago, and continues to be in contravention of a generous ceasefire agreement which it signed.

There is no doubt that there is kind of a gross incongruity in the way that Russia continues, in almost all manners and forms, to be treated as though nothing has happened. It’s almost as though Russia didn’t invade its neighbor and de facto annex large chunks of its territory, as though it still doesn’t suppress independent media, empower terrorizing local warlords, and commit severe human rights violations. Unfortunately, that pattern does not seem to be changing.

Still, there is reason for hope. Russia, for its part, is sure to be more protective of its 2018 World Cup than even the outsized attention that Moscow has focused on the Sochi games. The World Cup is a vastly bigger event, which means that its success is a prize on a whole other level of magnitude. One can be sure that Russia will tend to this responsibility with even greater concern and attention — perhaps even to a point that it might affect Russian foreign policy.

It all comes at an interesting time, too. As relations between NATO and Russia warm [4], Russia now just has yet another reason to moderate its seemingly genetic antagonism towards its neighbors and the West. The World Cup, being the event that it is, is supposed to be an opportunity to showcase its hosts as they want to be, and not necessarily as they are. This was no less true for Beijing’s Olympics in 2008 or for South Africa’s World Cup this past summer.

Of course, there is no guarantee as to how Russia will approach its task of geopolitical posturing now that it has two major events set for 2014 and 2018, with the latter being an even bigger deal. But it is worth considering, and hoping, that the force of the event’s significance will be enough to at least give the mighty Russia all the reason it needs to give the world some reprieve from the tyranny of its own paranoia and inferiority-complex.

Footnotes

[1] See: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1335188/World-Cup-2018-Russia-knew-won-24-hours-decision-made.html

[2] See: http://www.bigsoccer.com/forum/blog.php?b=8492

[3] http://jamestownfoundation.blogspot.com/2010/01/georgian-dimension-of-2014-sochi-winter.html

[4] See: http://www.evolutsia.net/a-russia-nato-alignment/