Argentina: A New Era Of Dialogue And Consensus – Analysis

By Carlos Malamud*

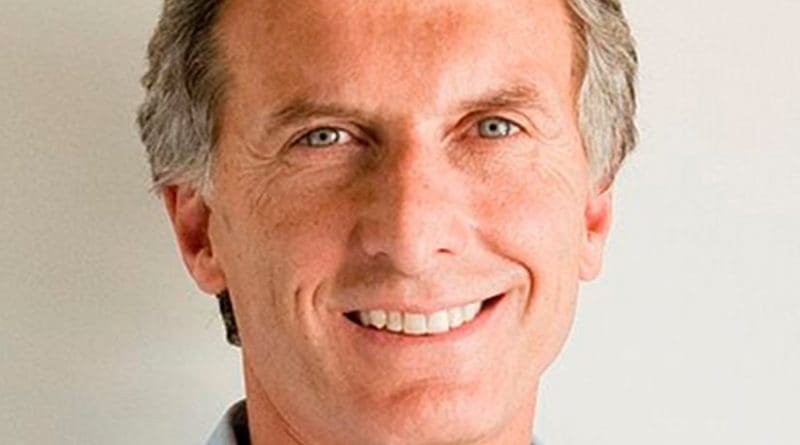

Mauricio Macri, Argentina’s new president, was the candidate standing for Cambiemos, the broad center-left and center-right coalition that defeated Cristina Kirchner in the recent elections. What Macri defeated above all was an ugly, black and white approach to politics that rejected bipartisan solutions and sought to foster polarization.

According to Ipsos Public Affairs, Cristina Fernández’s mandate came to an end with a 52% approval rating – not bad considering that everyone knows her family’s personal fortune multiplied 15 fold from 7 million to 100 million pesos in the course of three terms in office (two with her husband Nestor as the incumbent president and one with the widow at the helm).

Such a degree of positive recognition stems from the fact that “Kirchnerism” actually did some good things, especially in the earlier years when the main point of reference as perceived by Argentinians was the crisis of 2001 and 2002. Between 1998 and 2002 Argentina’s GDP fell by 18%, its currency lost 70% of its value and its per capita income in US dollars collapsed by around 68%.

According to the Kirchner governments’ official version (Néstor Kirchner, 2003-07, and Cristina Fernández, 2007-11 and 2011-15), the narrative of their years in power is that of the “saved decade.” The period is cast in a triumphal light, with significant successes at the outset fueled by favorable commodity prices and the expansion of the Chinese economy.

The reality today however, as President Macri takes over, is far more of a toxic than triumphal inheritance. The ‘saved decade,” it turns out, was more of a wasted opportunity disguised in statistical trickery and fake inflation figures.

The grand tragedy of the Kirchners’ era of governance is the failure to have exploited the tail wind of the golden years of booming commodity exports. A fair part of what was then accrued was subsequently dissipated in populist policies that failed to allow an increase in national savings or the accumulation of greater social capital for investment in the future, as shown by the exponential growth in the number of public employees and beneficiaries of state hand-outs.

Among the new government’s main economic problems is an inflation rate of over 25%, the second highest in Latin America after Venezuela. It stands in stark contrast to the “official” 14% reported by the National Statistics and Census Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censo or INDEC), proof of the government’s manipulated measurements. This is one of the leading points of disagreement between the Argentine government and the IMF, which prevented it over the past seven years from carrying out its annual updates. The IMF refuses to recognize Argentina’s official inflation data.

There is also the decline in the Central Bank’s reserves, dropping from a high of U.S. $52 billion in 2010 to the current U.S. $10 billion (although some speak of U.S. $5 billion or even less). To this should be added the restrictions imposed by the Kirchner regime on the acquisition of foreign currency for both companies and individuals, mostly affecting the U.S. dollar, which remains the Argentines’ preferred saving option. This is not to mention the pending negotiation with the so-called debt holdouts of foreign creditors presented by Fernández as an episode in the struggle against imperialism more than as a necessity brought about by government inaction.

Another no less important problem is the payment of subsidies, which consume a large volume of public income and have raised the budget deficit, which in 2015 accounts for 7.2% of GDP, the highest level since 1982, while subsidies themselves total more than 4% of GDP. In the budget approved for the coming year by the outgoing government, subsidies -mainly to the energy and transport sectors- total 179 billion pesos, 5% less than in 2015. Worse still, in large part they are directed at helping middle and higher segments rather than lower-income groups.

The new government’s inheritance is not only economic. Drug trafficking, corruption and public safety have become pressing challenges. A not unimportant contributing factor to the defeat of Kirchnerism, in addition to economic woes and the system itself running out of steam, has been the increase in crime rates and the feeling of vulnerability felt by the bulk of Argentine society.

As for foreign policy, a priority will be restoring a workable relationships with the country’s traditional partners -the US, the EU and other Latin American countries, including Colombia, Mexico and Peru- adversely affected by policies that favored new ‘friends’, such as Iran and Russia. Argentina’s international agenda was more in line with the recommendations of Hugo Chávez, who became a species of mentor for Fernández, than with the country’s own interests.

One of the Kirchner regime’s abiding traits has been its appropriation and colonization of the state. A striking example has been the outgoing President’s eleventh-hour attempt to retain her official Facebook, Twitter and Google accounts, something she looks unlikely to achieve. In her infantile tantrum of not taking part in the handover of power unless under her own conditions, Cristina Fernández went as far as to compare herself to Cinderella in her farewell address, which was more of a harangue to benefit her followers than an institutional speech marking the democratic transfer of power.

Macri’s arrival at the Casa Rosada will completely upend Argentine political life and the country’s style of government. Beyond the campaign of fear orchestrated by the Kirchnerists during the election campaign, a majority in Argentine society have decided to give a chance to the program advocated by Cambiemos. Mauricio Macri certainly does not have an easy job ahead and he can look forward to four very tough years. Hence the appeal, in his inaugural address, to dialogue and consensus. It would be desirable, for Argentina’s own good, over and above Fernández’s ambition of returning to power in 2019, that his term in office should be a success.

About the author:

*Carlos Malamud, Senior Analyst for Latin America, Elcano Royal Institute | @CarlosMalamud

Source:

This article was published by Elcano Royal Institute