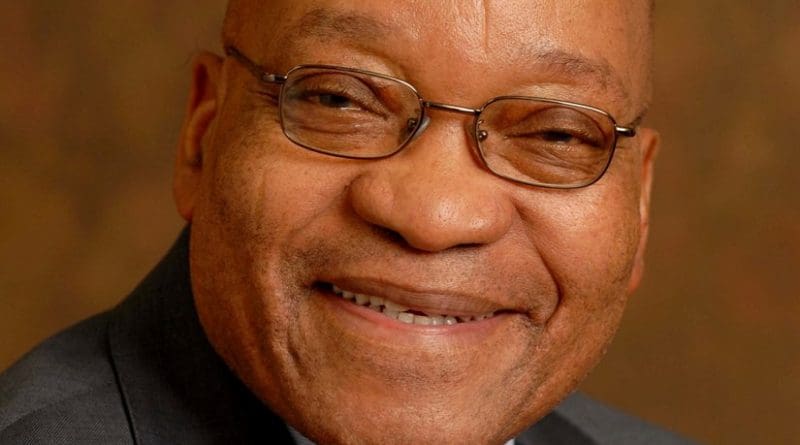

The Effect Of Zuma’s Imprisonment On South Africa’s Institutions And Rule Of Law – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Siviwe Rikhotso*

(FPRI) — In mid-July, violent riots and looting engulfed Johannesburg and KwaZulu-Natal following the sentencing and imprisonment of former South African President Jacob Zuma. On June 29, the Constitutional Court of South Africa handed down judgment on Zuma’s contempt of court case, sentencing him to 15 months in prison. This comes after the former president refused to comply with court orders in late January 2021 that he appear before a commission of inquiry for a second round of questioning after he has refused a summons. The court mandated that Zuma had to hand himself over to authorities within five days. Unsurprisingly, he defied the ruling as he had defied previous ones and instead held a press conference decrying the court’s ruling and describing himself as a victim.

Despite his initial bluster, Zuma handed himself over to authorities on July 7. The Zuma faction in the ruling African National Congress (ANC) responded by threatening unrest and national disruption if the former president was not released from prison. Following this announcement, criminal elements took advantage of the situation to ransack shopping centres, burning more than 40 cargo trucks and closing national routes to halt the delivery of goods. More than 300 people died, and over 1,200 individuals were arrested for participating. The unrest prompted President Cyril Ramaphosa to proceed with a highly anticipated cabinet reshuffle, which involved political infighting and the ousting of dissenters who opposed the political status quo.

The areas provoking calls for reform were lack of rule of law from the courts where high-profile and public figures are concerned, general lawlessness, violent killings as a result of the unrest, government restructuring, dissent within political parties, and a call for stronger democratic consolidation from both the state and the public.

A clear understanding of the causes of two months of violence and upheaval requires us to address the impact of one person: former President Jacob Zuma.

The “Zuma” Problem

Zuma’s tenure in office was characterized by widespread corruption, which gave rise to political and institutional decay. At the time of his election in 2009, Zuma was already facing corruption and fraud charges from 1999 when he was still deputy president. That case has never been resolved.

At the halfway mark of Zuma’s presidency, then-Public Protector Thuli Madonsela launched an investigation into Zuma’s conduct relating to the appointment of cabinet ministers, awarding of state contracts, violation of the Executive Ethics Code, and government intervention in non-state matters. Following a request by Father S. Mayebe of the Dominican Order of Catholic Priests, former Democratic Alliance (DA) leader Mmusi Maimane, and an unnamed member of the public, the Public Protector’s office investigated these complaints and released what came to be known as the “state capture report.”

The report describes “an investigation into complaints of alleged improper and unethical conduct by the president and other state functionaries relating to alleged improper relationships, and involvement of the Gupta family (a wealthy Indian-born family with business interests in South Africa) in the removal and appointment of ministers and directors of State Owned Entities (SOEs) resulting in improper and possibly corrupt award of state contracts and benefits to their family businesses.”

The report included testimony from ANC members Mcebisi Jonas and Vytjie Mentor on how they were invited to the Gupta estate and offered cabinet positions by the Guptas at Zuma’s behest. Zuma’s refusal to cooperate with the investigation, which limited the scope of the investigation due to lack of funding, prompted the courts to take seriously one of the report’s recommendations and order the president to establish a commission of inquiry to investigate allegations of widespread corruption by government functionaries and SOEs.

Commission of Inquiry and Zuma’s Incarceration

Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng appointed Deputy Chief Justice Raymond Zondo to chair the commission, which was established in 2018. To date, the commission has interviewed top government officials, including Zuma and Ramaphosa, as well as former and current directors of SOEs. The process intensified after Zuma ignored a summons from the commission. Noting this defiance, Zondo approached the constitutional court in December 2020 to compel him to appear. In response to the order, Zuma and his legal team appeared before the commission not to answer its questions but to request that Zondo recuse himself citing conflict of interest.

After Zondo refused this request, Zuma and his legal stormed out of the proceedings and mounted an unsuccessful appeal. Zondo then requested that Zuma be arrested and handed a two-year sentence for contempt of court. In June 2021, the court handed down a guilty verdict and sentenced the former president to fifteen months in prison. In defiance of the court order, Zuma turned himself in one day after the deadline, raising concerns among many South Africans about the supremacy of the constitution and constitutional court rulings and creating the impression that not all are equal in the eyes of the law.

The Zuma legal saga has been perhaps one of the most testing times for both the democracy of the country and the legitimacy of the high court. Predictably, the Zuma faction of ANC, including the influential Military Veterans Association (MKVA), protested Zuma’s incarceration, citing it as highly political and targeted and maintaining that the legitimacy of the judiciary was compromised.

The Aftermath

After Zuma turned himself in, high-profile members from the ANC’s Zuma faction instigated civil unrest that resulted in the death of more than 300 people, the looting and burning of shopping centers and cargo trucks, the closure of national supply routes, and the arrest on live TV of MKVA Spokesperson Carl Niehauws. President Ramaphosa mobilized 25,000 members of the military to assist the police in quelling the riots, due in large part to the South African Police Service’s sluggish response.

The violence is estimated to have cost the South African economy R35 billion, (US$2.4 billion) although government sources say it could rise to R50 billion (US$3.4 billion). It is estimated that KwaZulu-Natal alone suffered R20 billion (US$1.4 billion) in losses, and a staggering 150,000 may lose their ability to generate revenue. In addition, 40 cargo trucks were burned, causing another estimated R500 million (US$338 million) in losses.

Coal exports stopped for over a week, which added R1 billion (US$68 million) in losses. Other exports also stopped when the harbors were closed. In addition, loss of investor confidence caused by the unrest, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, generates turbulence that will be felt by the South African economy for an extended period. The possible downgrading of South Africa by ratings agencies and the potential of slower economic growth compound all these issues.

President Ramaphosa’s recent cabinet reshuffle is not totally isolated from the turmoil. It has definite undertones of cleaning house to rid his administration of multiple centers of power that may potentially undermine his authority. For example, he abolished the security ministry and placed the “political responsibility” for the South African spy agency under his office. This, he said in a televised speech, was “to ensure that the country’s domestic and foreign intelligence services more effectively enable the president to exercise his responsibility to safeguard the security and integrity of the nation.” In addition to changes in security posts, he also replaced several officials in economic and health positions.

In September 2020, former Minister of Defence and Military Veterans Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula publicly defied Ramaphosa when she allowed senior ANC officials, including suspended ANC Secretary General Ace Magashule (who is facing corruption and fraud charges), to hitch a flight on a state aircraft to Zimbabwe to discuss regional security issues. While given permission by Ramaphosa to charter a South African Air Force plane, Mapisa-Nqakula allowed party delegates to ride on the aircraft, sending a message that state resources are used to enable party activities.

Political dissent, even before Zuma’s incarceration, has been one of the major factors at play in the Zondo Commission as well, apart from the mounting pressure from the public and investors to eradicate official graft and corruption. An investigation of the instigators of the unrest is ongoing. Intelligence has revealed that prior to the outbreak of violence a WhatsApp group was established with the purpose of discussing and organizing logistics. More than 12 “high-profile” suspects have been detained or arrested in connection to the unrest.

The Zondo Commission’s findings and the unrest following Zuma’s incarceration have not only shown the fragility of the rule of law in South Africa, but it also revealed the deepened racial tensions as KwaZulu-Natal is deeply divided along racial lines over the killing of 36 people during the unrest.

Police Minister Beki Cele stated that this was in part due to racial profiling in the suburb as a reaction to the unrest. Vigilantism by community members and private security firms are being investigated in connection with the murders, and already 22 suspects have been arrested and charged with murder, attempted murder, and grievous bodily harm. Racial tensions have always been a thorn in the country’s democracy, owing to South Africa’s history, and this incident, like many others before it, demands the government’s urgent attention as issues of human rights and equality come to the fore when murders with racial undertones occur.

What Does All This Mean for South Africa?

Zuma’s incarceration and the aftermath sparked fears nationally and internationally of chaos and anarchy that seems to have been intended to render the country ungovernable. Undoubtedly, Zuma will remain infamous for his tenure in office, his corruption and fraud charges, allegations of further corruption that may have lost the country billions in taxpayer money, his factional politics and tendencies that have made a public spectacle of the ruling party, and the recent fear of anarchy and chaos caused by his incarceration. Zuma certainly has caused South Africans to ask themselves and each other whether the country’s democracy and judiciary are strong enough to withstand the effects of his imprisonment. Certainly, many within his camp had thought and possibly hoped that one man and his refusal to bow to the supremacy of the law would shut down the country.

The audacity of his supporters to give the country, not just the government and independent judiciary, an ultimatum to meet their demand is shocking yet unsurprising. The foundations and pillars that South Africa’s democracy was founded upon have stood firm—not just in the historic Zuma verdict, but also in the manner in which communities, residents, and the public at large stood with the law and government to root out unrest and prevent lootings.

Apart from the unrest caused by Zuma’s jailing, the country’s democracy and institutions are in a state of decay. The ruling party is engulfed in political infighting, destroying itself from within and leaving little work for the opposition parties. President Ramaphosa inherited a party governed by a “quid-pro-quo” situation where appointments are made based on factional affiliations and personal loyalty. Currently, there are three centers of power within the ANC. The Ramaphosa faction, the Zuma faction, and the Magashule faction, which is closely associated with the Zuma faction but in decline.

Perhaps, one of the more observable tendencies of this is in the top positions in the party and the government, where it seems members must have “struggle credentials” of having served the party during the fight against apartheid to be considered for an influential position, which in turn they use to grant special favors to those who put them in that position and to their cronies. The majority of people in government and party leadership positions are over the age of 50. There is a severe shortage of youth to reinvigorate either the cabinet or the party.

What Can Be Done?

Unless confronted at all levels of government, corruption and graft will continue to erode democracy and rule of law. State officials should not feel that they are untouchable by the law because of connections and political affiliations. The justice system needs to ensure that it remains as impartial in high-profile court cases as it tends to be in low-profile cases.

A large part of mass public distrust in the system is related to the arrest and release of suspects who are able bribe their way of out prison sentences. Moreover, the security sector in the country, particularly law enforcement, needs reforms that will ensure effective response to crime of any kind anywhere in the country. The sluggish reaction to the July unrest is just one of many examples of how law enforcement has declined in South Africa.

After the week of violence and unrest, order seems to have been restored, but retailers and the state are not confident that the unrest has been completely quelled. Military units still patrol the streets, and shopping centers and malls have military and police units providing security. The national highways have military observation posts and security checkpoints, and trucking companies have private security units accompanying their trucks to ensure that deliveries are on time and that trucks are not damaged. This conveys a level of insecurity as the government has not yet confirmed that all instigators of the unrest have been apprehended.

Lastly, while the country certainly has room for improvement, the character and resilience that it has shown in one of its darkest hours is worthy of commendation because the aftermath of Zuma’s incarceration showed that the majority of South Africans still believe in their justice system and in their democracy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy-oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities.

*About the author: Siviwe Rikhotso is a Geopolitical and Foreign Policy researcher at the African Centre for the Study of the United States (ACSUS).

Source: This article was published by FPRI

” The Zuma faction in the ruling African National Congress (ANC) responded …Following this announcement, criminal elements took advantage of the situation” For some reason the writer distinguishes between the two whereas in fact the *entire* ANC has supported the criminal industrial-scale looting of the country. The non-Zuma faction includes current President Ramaphosa, who was Zuma’s deputy hence part of the looting while the ANC Parliamentary caucus voted on numerous occasions to support Zuma and overrule efforts to bring him to account (such votes being deemed, by SA legislation, as criminal and corrupt)

The violence was an ill-considered attempt to overthrow the country’s constitution and can be compared to Trump’s failed attempt to overthrow his country’s constitution, albeit the latter was focussed on the Capitol and had less violence. In both cases the military did not side with the insurrectionists and the countries’ constitutions held firm.