Kazakhstan: Latin Alphabet Not A New Phenomenon Among Turkic Nations – OpEd

By Eurasianet

By Uli Schamiloglu*

Kazakhstan’s planned transition to the Latin alphabet raises complex questions. While alphabets may not be important in and of themselves, they play an important role in helping define a nation’s place in the world.

As a Turkologist, I regularly teach a range of historical Turkic languages using the runiform Turkic alphabet, the Uyghur alphabet, the Arabic alphabet and others. Turkologists also study various Turkic languages written in the Syriac alphabet, the Armenian alphabet, the Hebrew alphabet, the Greek alphabet and others.

Stated briefly, you can use a lot of different alphabets to write Turkic languages. From a technical point of view, it is just a question of how accurately any particular alphabet represents speech sounds.

The classic version of the Arabic alphabet — with additional letters introduced for Persian — does not represent the vowels of Turkic languages accurately. Nevertheless, it was used successfully for Chagatay Turkic in Central Asia and Ottoman Turkish in the Ottoman Empire until the early 20th century. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, innovations were introduced to represent vowels more accurately, and this is certainly the case with the reformed Arabic alphabet used currently for Uyghur.

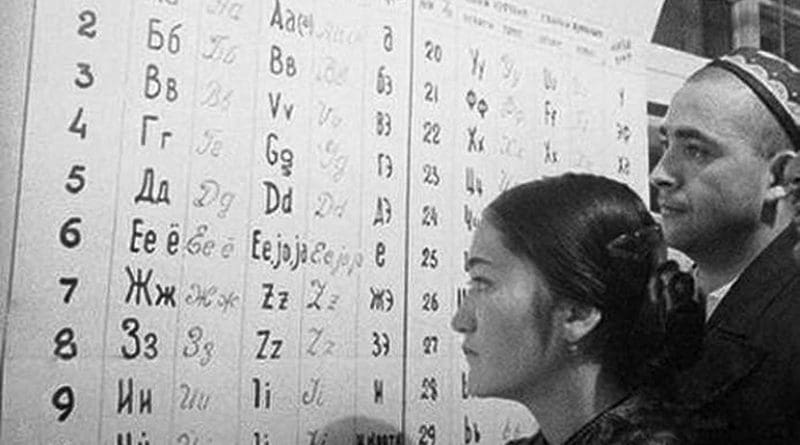

Using the Latin alphabet to represent Turkish languages is not a new phenomenon. The alphabet was used to write the Codex Cumanicus in a dialect of Kipchak Turkic in the early 14th century. More recently, Turkey adopted one version of the Latin alphabet beginning in 1928, as did Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan from 1991, and Uzbekistan in 2001, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

We should also recall that in the early Soviet period most of the Turkic languages of the union shared a common Latin alphabet — the so-called Yangälif — beginning in 1926. But this alphabet was soon superseded by individual Cyrillic-based alphabets that were different from each other.

There are several linguistic factors supporting Kazakhstan’s planned switch to the Latin alphabet. One, of course, is that the Latin alphabet is familiar to a far larger number of educated persons than the Cyrillic alphabet. It is also used widely for communication over the internet and cellular telephones.

Far more significant to me personally is another phenomenon that I have often observed. Speakers of Kazan Tatar — and I am myself of Kazan Tatar heritage — Kazakh and other languages who may not be fluent in their ostensibly native language often impose the pronunciation and phonological rules of the Russian language and the Cyrillic alphabet on their own language.

To explain it in technical terms, front vowels in Russian palatalize the preceding consonant. So it is that you have speakers of these Turkic languages pronouncing words as though they were written in Russian — “spelling pronunciation” as it were. In other words, they pronounce words in their own language with a “Russian accent.” I have even encountered speakers of Kazakh learning Turkish who pronounce Turkish according to the rules of Russian pronunciation. There is every likelihood this phenomenon will be disrupted if schoolchildren are exposed to the Latin alphabet from an earlier age.

So, yes, I am in favor of the transition of the Kazakh language from the Cyrillic alphabet to the Latin alphabet.

Beyond the linguistic phenomena, there are political, cultural, and even ideological elements to consider. In other words, will Kazakhstan remain forever identified with the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union that succeeded it? Or does it wish to be seen as part of a larger world community, including the European community, of which it is also a part?

Another question is whether the Kazakh nation — and I am thinking here of ethnic Kazakhs, rather than all Kazakhstanis — should remain apart from the rest of the Turkic world. Turkey, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan have all adopted some variation of the Latin alphabet. Kyrgyzstan is also considering such a move. What would be the argument for Kazakhstan to remain isolated from this large part of the Turkic world, especially when there is sentiment in other parts of the Turkic world to adopt the Latin alphabet? (It is believed Tatarstan too would consider the transition were they to be permitted to do so, although it is currently against the law in Russia to use an alphabet other than Cyrillic).

Arguments against the adoption of Latin are inherently grounded in imperial Russian or Soviet ideology.

Beginning in the late 19th century, the various Muslim Turkic peoples of the Russian Empire were beginning to explore modern identities. I have argued elsewhere that the Kazan Tatars of today began to advocate for a Tatar territorial nation already in the 19th century, whereas many other Muslim Turks in the Russian Empire advocated for a non-territorially based shared identity extending across the Turkic world, and more broadly across the Muslim world.

The latter view raised concerns over “pan-Turkism” and “pan-Islamism” among authorities in the late Russian Empire — views that persisted during the Soviet era and beyond.

One of the underlying notions against the Kazakh language switching over to Latin is this irrational colonial-era fear of the unity of Turkic-speaking peoples.

Given the growing cultural integration of the Turkic world through the founding in 2009 of the Cooperation Council of Turkic-Speaking States — which was established by Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkey — and the growing role of Astana as a new cultural capital for the entire Turkic world, why shouldn’t Kazakhstan try to develop closer cultural connections with other Turkic republics via a similar alphabet?

My late father used to talk about how Kazan Tatars became illiterate twice in one generation, first as the Arabic script was abandoned in favor of the Yangälif, and then again when that “new alphabet” was abandoned in favor of Cyrillic. Individual Cyrillic alphabets were introduced for Soviet Turkic languages in the 1930s; Kazakh adopted the Cyrillic alphabet only in 1940.

There are inescapable social costs to this change, such as the older generation potentially becoming illiterate, or at least disadvantaged. Then there is the cultural cost, such as the younger generation potentially becoming cut off from its past — for the second or third time! Turkey experienced this shock beginning in 1928, and it still has not gotten over it completely. Although Turkey undertook this as a kind of “shock therapy,” Kazakhstan has chosen a gradual path by choosing the final form of the alphabet by the end of 2017, training educators in the new alphabet, and then finally completing the switch to the Latin alphabet by 2025.

At the same time, there is a political dimension to the process. Russia has very strong feelings about the Russian-speaking world and its position of dominance within it, even though its actions have often arguably undermined its own interests in this respect. Russia would naturally prefer not to see Kazakhstan abandon Cyrillic. Whether it will take any steps to prevent this from happening will be discovered soon enough. I hope not.

It is now official policy in Kazakhstan to promote three languages through the educational system — namely Kazakh, Russian and English. I think it is well documented by now that the Russian-speaking space is in decline throughout the former territories of the Soviet Union. But Kazakhstan, like Tatarstan, is so strongly bilingual that I am not worried so much that the use of Russian will decline in Kazakhstan any time soon. The real challenge is to make sure that Kazakh becomes viable as the official language of Kazakhstan.

Unlike in Turkey, or say Uzbekistan, Kazakh has a long way to go before it becomes the default language of choice among citizens of Kazakhstan.

*Uli Schamiloglu is a professor in the Department of Kazakh Language and Turkic Studies at Nazarbayev University in Astana, Kazakhstan.