Russian Defeats Are Forcing Moscow To Shift From Propaganda To Crisis Communications To Insulate Putin – OpEd

By Paul Goble

The failure of Russian forces in Ukraine to achieve promised victories and the beginning of ever more defeats in the field hs forced Moscow propagandists to shift from propaganda mode to crisis communications, a tactic intended to protect Putin from criticism but one that raises the stakes all around, Grigory Asmolov says.

The instructor at King’s College London says that the fact that Russian media so overwhelmingly predicted quick victory has been an “Achilles’ heel” now that victory has been postponed if not made completely impossible. In this situation, the authorities have had to change course (ridl.io/crisis-propaganda/).

“For the first time since the start of the war, pro-Kremlin communicators have had to move beyond propaganda methodology into the realm of crisis communication,” Asmolov says, by providing an alternative narrative in order to protect those at the top from criticism for their role in the failures.

“While propaganda can involve a wide range of tasks to build support for certain actions,” he continues; “crisis communication forces the propagandists to defend themselves.” In it, their task involves providing answers to two questions: “Who is to blame?” and “What should be done about it?”

Before a crisis, propaganda helps to achieve political objectives by influencing target audiences. But in a crisis, the preceding propaganda campaign becomes an aggravating factor.” As a result, “the symbolic resources of propaganda narratives are no longer sufficient to interpret the frontline news.”

In this new context, “the simplest way to cover the crisis and to go beyond propaganda was to look for those responsible for the developments. The Kremlin apparently did not manage to prepare an effective communication strategy to explain what had happened, so the easiest solution to bring the situation under control was to resort to threats and reprisals.

But intimidation as a crisis management tool is an increasingly limited tool “especially if the crisis drags on. Moscow’s crisis managers have sough to do two things: identify the mistakes that led to Russian retreats and identify those responsible for those mistakes in such a way that Putin and his immediate team would not be blamed.

Those appearing on Russian talk shows have identified three groups to blame: those who weakened the army earlier by their liberal reforms, those lower-level officials who had failed to do what they were ordered to do and then lied about it, and those who spread panic by being overly critical of the Russian authorities.

Propaganda about the war has continued alongside crisis management techniques, but it can succeed only if it continues to raise the stakes as to what the conflict is about, Asmolov says. Hence, its ever-increasing focus on NATO and the West in general rather than on Ukrainians in particular.

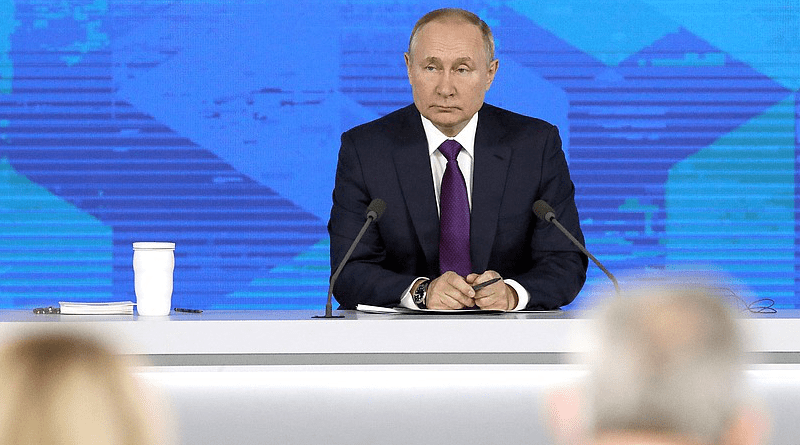

As Asmolov observes, “ever since Vladimir Putin came to power, Russia’s history can be developed through attempts at crisis management,” from the Kursk disaster at the dawn of his rule to Ukraine now. While his resources now appear much greater than 20 years ago, his expanded control over the media comes with a price.

And that is this, the analyst says, “increased over the media increases the risks associated with the aftermath of a crisis.” Crisis communications has made “a force correction, but as it operates within the existing logic of war coverage, its main task is to create a new basis for a new wave of propaganda.”

In this, Asmolov says, Russian propagandists increasingly resemble the mythical Ourobos, “a serpent that eats itself.” With each new crisis, “the serpent’s tail gets ever deeper into its mouth, leading to the point where self-absorption will lead to the annihilation of the one doing the absorbing.”