NATO’s Open-Door Rhetoric On Ukraine Is Running Up Against Harsh Realities – Interview

By RFE RL

By Vazha Tavberidze

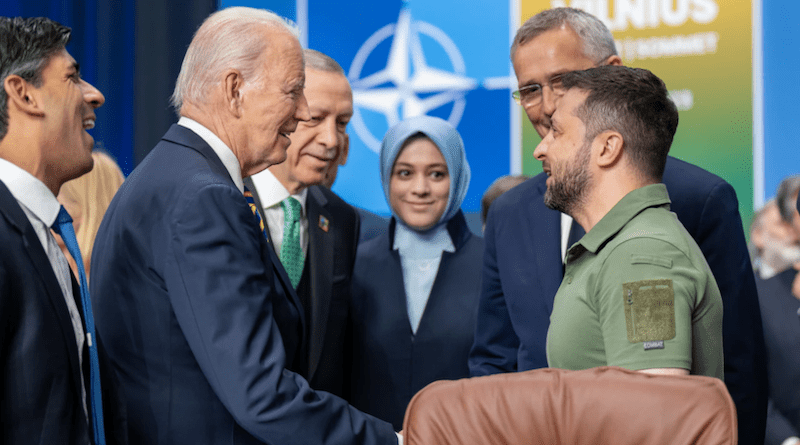

(RFE/RL) — Nikolas Gvosdev is a professor of national security studies at the U.S. Naval War College who focuses in part on Russia and U.S. foreign policy. In a recent interview with Vazha Tavberidze of RFE/RL’s Georgian Service, Gvosdev argues that the recent summit in Vilnius showed NATO’s failure to forge a “shared strategic outlook” on Ukraine and that the military alliance is just kicking the can down the road.

RFE/RL: What have we learned in Vilnius at the recently concluded NATO summit?

Nikolas Gvosdev: What we’ve learned at Vilnius is that NATO is an unwieldy alliance of 31 members. It is difficult to get consensus and what we ended up with was a lowest-common-denominator approach to many of the issues including the contentious question of Ukrainian membership in NATO, and under what conditions Ukraine might be invited to join the alliance.

And it was not only just simply the Central and Eastern European states of Poland, the Baltic republics, that were pushing for an invitation to Ukraine, and the traditional opponents in Germany and France that might have been opposed, but also [there was] this very ambivalent approach of the United States, which I think really caught a number of observers by surprise.

When we think about the Bucharest summit in 2008, the United States was pushing very hard for Membership Action Plans (which spell out steps and conditions for NATO membership) for both Ukraine and Georgia at the time. And in 2023, at Vilnius, the United States was not full-fledged in its support for moving Ukraine immediately toward getting an invitation.

And in some ways, it’s a worse situation, I might add…by removing the Membership Action Plan requirements, [because] at least Ukraine would have an understanding of what they would have to fulfill. Now we have this very vague formulation that says, well, Ukraine will join when conditions warrant and the allies agree. And that doesn’t give us a lot of clarity as to what are the conditions? When will they be met? Who will evaluate whether the conditions have been met? And what does it mean for the allies to agree?

So, in some ways, this summit worsens Ukraine’s position in that Ukraine doesn’t have a clear invitation, it doesn’t have a timeline, but it also doesn’t have, at least from the alliance, concrete security guarantees. And now what is going to happen in the aftermath of Vilnius, which is going to be critical, is whether or not individual countries, starting with the United States, are going to extend clearer, firmer guarantees of support to Ukraine, [which] the alliance — as the alliance — was unwilling to do in Vilnius.

The point, again, is the alliance does not have a shared strategic outlook on Ukraine beyond the agreement that everyone agrees Ukraine should be supported against the Russian invasion…. And, of course, the other part of the summit, which [concerned] NATO’s role in the greater Indo-Pacific region. Should NATO as NATO be involved vis-a-vis China? And, of course, the perennial issue of NATO versus the European Union — what should the European states be doing in terms of defense? Because the other elephant in the room is the recognition that, sooner or later, the United States’ focus is going to be drawn to the Pacific region. And is Europe capable of holding the security situation in the absence of a major American commitment?

RFE/RL: Let’s make a quick detour, a very brief detour to Sweden. It’s been greenlighted for NATO membership by Turkey at last and I think the most obvious question is: What is Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan getting out of it? Because, if his record is anything to go by, he’s not doing this out of kindness of his heart or the lofty ideals of empowering NATO and the proverbial West. So, what’s the deal? What did he haggle over?

Gvosdev: I think he’s haggling over suspended U.S. military assistance, after his decision to acquire the [Russian] S-400 [missile system]. I think he’s looking for an end to efforts in the U.S. Congress to sanction Turkey for a wide variety of its activities, including its economic activities with Russia. I think that Erdogan is saying, “I will move forward on Sweden, I want F-16s (U.S. fighter jets), perhaps a return to the F-35 (U.S.-led fighter jet) program. But I also don’t want to see talk about sanctioning Turkey for its business relations with Russia” — [which] is part of this as well. And again, for all the people saying, “Well, Turkey has now approved Sweden,” all that Erdogan is committed to is submitting the documents for ratification [in the Turkish parliament] and that could be a prolonged process. And the interesting test will be who ratifies first. Will he ratify first, or will he want to see if the Biden administration can convince a skeptical U.S. Congress to move on some of these issues vis-a-vis Turkey?

Obviously, [Erdogan’s] European Union [membership] bid was more for grandstanding. It’s clear that Turkey is not going to necessarily move forward on its EU bid. So, you’re right. This isn’t about altruism, or about a greater strategic vision. Erdogan has some pretty clear deliverables he’s expecting for moving forward on Swedish membership.

RFE/RL: Another quickfire question — let’s talk about the U.S. reluctance. How much of a role does uncertainty ahead of the 2024 presidential election play in all this?

Gvosdev: It plays a great deal. And this has to do with assumptions that the [U.S. President Joe] Biden administration made about the timeline. If you look back eight, nine months ago, the U.S. hope was that by the time Vilnius happened, Ukraine would have had made substantial gains in a counteroffensive; that they would — if not have retaken Crimea and Donbas — they would have seriously damaged the Russian position. This was supposed to then allow for a discussion at Vilnius about security guarantees for Ukraine, where the fighting would essentially stalemate on terms that would be favorable to Ukraine.

What you now have is a U.S. administration that is faced with an unpleasant dichotomy, which is: If you offer security guarantees to Ukraine, including a pathway to NATO membership, you are doing so at a time when Ukraine has not succeeded in regaining control of most of the lost territory. And so, you’re either asking Ukraine to freeze the boundaries, the lines of control, as they exist now. Or Ukraine says we need more time to engage in counteroffensive operations.

But then, of course, the worry in the U.S. is that this is going to draw the United States more directly into the conflict, which the Biden administration does not want on the eve of an election.

The polling data in the U.S. is quite clear: there’s strong support for supporting Ukraine; there’s not a lot of support for direct U.S. engagement or involvement in the conflict.

And as you move into an election year, you don’t want to essentially be saying you are committing the United States to a military or greater military role…. Greater involvement by the U.S. is not something that is a political winner. And I think that the initial hope for Vilnius was that Ukraine was largely back in control of most of its territory by this point, [so] you could then say: “As we did with [U.S. miliary support for] Korea, as we did with Germany, we can bring you into NATO, because you control most of your territory.” And that can be done. But it’s that dichotomy, [because] Ukraine really isn’t ready…to concede permanent loss of Crimea or Donbas. And therefore, the United States isn’t going to offer security guarantees, as long as Ukraine itself is not happy with the current disposition of forces where they happen to be aligned.

RFE/RL: The adopted NATO communique says: “We will be in a position to extend an invitation to Ukraine to join the alliance when allies agree and conditions are met.” What are these conditions?

Gvosdev: We don’t know. We don’t know what the conditions are.

RFE/RL: Due to this, I’ve seen this summit dubbed as Bucharest revisited. Is that a deserved, justifiable moniker?

Gvosdev: Unless in the days following Vilnius, the alliance clarifies what that [statement] means, then it has very much these echoes of Bucharest (at the 2008 NATO summit). Because right now, one could say, “Well, as long as we don’t know what the conditions are, they can never be met.” There’ll never be time for Ukraine.

RFE/RL: Let’s delve deeper into the NATO lingo a little bit. Let’s discuss some of its more classical tenets that we’ve been listening to for more than a decade now. Let’s start with: “NATO has an open-door policy.” Does it really? How come it’s open and Ukraine and Georgia are shuffling their feet at the doorstep for so long?

Gvosdev: That’s a great point. It’s an open-door policy where, in many cases, NATO countries are very, very eager for people not to voluntarily [go through] the door. And so, “Yes, the door is open, but please don’t. It would be really wonderful if you didn’t actually take us up on it.” And I think you’ve seen that particularly with Ukraine and Georgia over the last 10 years, which is: “Yes, the door is open, but really, we don’t want to close the door, but it’d be really wonderful if you don’t come through it.” And then of course, what we’ve seen in Georgia is some politicians saying, “Fine, we’re not going to. If we’re not going to come in, then we’re not going to do any of the things that you would like, because we know that we’re not going to [go through] the door.” And that I think, again, is a disingenuous political statement to try to get around the fact that nobody wanted to say that Russia gets a veto.

RFE/RL: Which is another one I was going to ask you about.

Gvosdev: Russia doesn’t get a veto. But we really like it if you didn’t actually enter the alliance. And this actually hits on another point from NATO-speak, which is important. And it’s not NATO-speak as much as its members, politicians, who then say — and you saw this at Vilnius — “Well, Ukraine is virtually a member of NATO.” And you’ve heard that about Georgia.

But there’s no virtual membership. There’s no such concept. There is membership and there’s nonmembership. Now the third option, which would be — and which we did not see at Vilnius — is NATO could start to conceive of associations; that the alliance has associations with countries. We have these partnerships and the Partnership for Peace [program]. But I’m talking about associations that would have binding guarantees and commitments. But we saw no move in Vilnius. And I can understand from the Ukrainian perspective the worry is, “Well, this is a way not to get full membership, because you’re going to give us this association status.”

RFE/RL: On this view, “The door is open, but please don’t come in,” there have been so many pop culture references popping up on the Ukraine war and one of them has been from Lord of the Rings with Russians portrayed as orcs. And I don’t know if you’re a fan of J.R.R. Tolkien’s work, but this very much sounds like hobbit politeness. When hobbits say good day, they actually mean goodbye.

Gvosdev: I think that’s a great analogy. It is a hobbit politeness…because so much of what [NATO] — particularly the U.S. government — wants to avoid saying is “No.” They don’t want to say to Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Moldova: “We don’t really want to bring you into NATO.” They don’t want to say, “No.” So, they say, “The door is open.” But it is this hobbit approach. And it is complicated by the fact that there are people certainly within the U.S. government, in the Congress, that do want to bring these countries in. But there is enough of this reluctance that it creates this impression. Then the problem when you say, “Open door, you’re virtually a member of NATO,” is we’ve seen how Russia uses this in its own information warfare to say, “Well, see, Ukraine is virtually a member of NATO, so we had to do the special operation.” We saw that from Dmitry Medvedev (former Russian president and now deputy head of the powerful Security Council) and others who said, “Well, NATO already says they’re effectively in, so we had to go in.”

And so, it doesn’t really help the countries to say, “The door is open but don’t come in, you’re virtually a member.” And then for them to be left holding the bag, as Georgia was in 2008, as Ukraine has been in 2014, and again, after 2022, where you get hopes and prayers…[and] in the case of Ukraine, certainly a lot of military equipment and financial assistance, but no guarantee that the alliance is committed to reversing the Russian invasion.

RFE/RL: Should the bottom-line reading on this be that the West is still unsure about a security structure of Europe centered against Russia, and it still might be entertaining hopes to bring Russia back to the fold?

Gvosdev: I think those hopes are diminishing. I think even in Germany, which has been sort of the epicenter of that approach, about [how] Russia needs to be part of any European security structure — that’s diminishing. But I think what it’s being replaced by is a hope that, “Well, there’ll be a new line and…we can have a settlement with Russia [where] maybe Ukraine doesn’t control all of its territory.”

We saw right after 2008, Europe, particularly under [former French] President [Nicolas] Sarkozy, was perfectly happy for a settlement that would leave Georgia detached [from] 20 percent of its territory as well. By the way, I don’t think that France or Germany would consent to have 20 percent of their territory detached and then just simply say, “Well, that’s the price you have to pay.”

And so I think, again, some of this open-door rhetoric is running up against an unwillingness to pay some of the costs and we’re seeing it [now]. What Vilnius, by the way, has done is again, it kicks these issues down the road. So, the Wales summit in 2014, Madrid last year, to which Vilnius was supposed to build on. And now we’re seeing that, well, Vilnius kind of repeats Madrid, and now [on to] the next summit.

RFE/RL: An unending source of tomorrows.

Gvosdev: Yes, the unending sources of tomorrow, and so it’s next year’s NATO summit (in Washington, D.C.) that will have to be different. But the problem with this for Europeans is that the United States pivoted back to Europe after the Russian invasion. Next time, that may not happen.

RFE/RL: And if you’re sitting in the Kremlin, how do you look at it, what’s the perspective? Could one argue that these half measures serve as the incentive for Russia to never end the war?

Gvosdev: Precisely right. Because the way that so many Western leaders coming into Vilnius said, “Well, Ukraine is only in when the war is over, then we’ll move.” Then you’ve signaled to Moscow that the war never needs to be over and the war can continue. This is why the Korea precedent is so important. Technically, there is still a state of war on the Korean Peninsula. And so it doesn’t mean that you have to have active military operations every day. Essentially, you’ve signaled to Moscow: don’t settle, just keep this going. The Russians have shown that they can sustain a level of operations in Ukraine. And, by the way, to continue to wreck Ukraine in a way that makes the bill for reconstruction go up and up. And to make Ukraine even less attractive as a partner two, three, four years down the road.

RFE/RL: I know you’re a very staunch believer that this eventual U.S. shift and pivot to the Indo-Pacific region is something that is irreversible and inevitable. Right?

Gvosdev: Yes.

RFE/RL: Let me ask you then a quick question from that perspective. Isn’t it in the U.S. interest to leave Moscow in a state that it’s of no concern, security-wise, in case there really is a future confrontation with China?

Gvosdev: Well, part of that is the idea [of whether you want] to focus so much on Russia over the next several years [now] that China has made some irreversible, irrevocable gains in the Indo-Pacific region that become a lot harder to dislodge versus a Russia that has been sufficiently weakened, which is still a problem but not an overwhelming threat….

But the question here is that the United States needs to be able to focus time to really rebuild and strengthen relationships that do not just simply dissipate once there’s a crisis in Europe. This is the problem. The United States approach in Asia can’t be episodic, where there’s a problem and we pivot away and then we say, “OK, but we’re going to come back.”

We’re at a critical point where key partners of the U.S. are prepared to really line up with the U.S. in much greater security arrangements. Not like NATO, because NATO is not a template for the Far East, but to really deepen those commitments. But they want to see that the United States is going to be able to see through those commitments. And that has to do also with the defense industrial base: what you can provide, what number of forces are available, where the attention is going to be. And so again, I think the [Biden] administration had this sense that really by Vilnius, the Ukraine question was largely going to be wrapped-up, settled, not necessarily 100 percent.

RFE/RL: Would that have been wishful thinking considering that they did not supply Ukraine, apparently, with enough to achieve that objective?

Gvosdev: Well, because I think over last year, they overweighted the impact of the sanctions on Russia. That they really thought that the Russian economy could not sustain sanctions pressure. It was going to collapse in on itself, which it has not. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t economic problems in Russia. But the Russian defense industry has been more resilient than I think the West assumed, with its ability to continue to supply the Russians with equipment and, therefore, as you said, not enough supplied [by the West to Ukraine] at the beginning; a pipeline that is slower than expected to get this [done] and Russia’s ability to continue to keep the campaign going.

RFE/RL: Your thinking implies that there is no day-to-day thinking in the Pentagon or in Washington, that they think a year ahead and then they go to hibernate and wake up half a year later. Could they not see that this is not working out as intended? Why did we not see any adjustments?

Gvosdev: One of the weaknesses of the U.S. strategic approach is: “We like to work on our timelines, we establish a timeline, and then we expect reality to conform to the timeline that we’ve established.” We saw this in Iraq; we saw this in Afghanistan.

RFE/RL: Don’t you check up on the timeline?

Gvosdev: You do check up, but this is confirmation bias. You look for the signs that confirm that your preferred timeline is working, and you ignore the signs that they aren’t. How many times over the last year were we told that Russia was out of missiles? It’s been like clockwork. Every two weeks, we get a report: “Russia has exhausted its missile supplies, it’s done.” And maybe Russia is more adaptable…. I think we’re now beginning to realize that we overestimated their vulnerability to sanctions. We underestimated their ability to repurpose old military equipment and use it in Ukraine to some degree of effectiveness. And that has implications down the road for how much to [send to] Europe and how much to Asia?

RFE/RL: How did that thinking occur, to realistically think that Ukraine would be liberating territories, including Donetsk and Crimea, by the time of the Vilnius summit?

Gvosdev: It’s the outgrowth of Ukraine’s successful operations last August. So, the assumption was that when Ukraine regained control of Kherson, when they cleared the Kharkiv area, that this was the template moving forward…. The military has this expression: “The enemy gets a vote.” And the Russians, [Sergei] Surovikin (deputy commander of the Russian group of forces fighting in Ukraine) exercised that vote, which was to spend the next six months building very robust defensive lines all across southeastern Ukraine.

There was also a sense that, “Well, the Russian political system is fragile, the military is not going to fight, the sanctions are going to work.” All of our best-case scenario options were then assumed to be that: “Well, that’s what’s going to happen.” Because I’m much more of a pessimist, I always assume that the worst case is what’s likely to happen. So, I’m not surprised. And now this again, this opens up a very big question moving forward after Vilnius, which is, in the absence of NATO moving on Ukraine, the individual, bilateral security guarantees — what’s going to come from that?

RFE/RL: On the sidelines of the Vilnius NATO summit, interesting things were transpiring. A so-called G7 security pact, heralded by former NATO Secretary-General Anders Fogh Rasmussen and Andriy Yermak, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s chief of staff. According to Rasmussen, “It includes transfer of NATO standard weapons, enhanced intelligence-sharing, a major expansion of training and exercises with Ukrainian forces, and support to develop Ukraine’s military-industrial base.” What do you make of this? Could this be the prelude to the much-discussed “Porcupine” scenario, where Ukraine is turned into a fortress packed with modern weaponry?

Gvosdev: Yes, look, the first thing is that doing this under the umbrella of the G7 is quite interesting. The G7 [Group of Seven leading industrialized nations] is traditionally an economic forum. It’s odd to have a major security initiative like this come through the G7. It reflects that you could not get it through NATO. And that in and of itself is a telling sign.

The second question is: How much of this is already things that are already being done? Is this going to be something substantially different than previous waves of intelligence-sharing, military equipment provision, training? Is it going to be substantively different? Is it going to be connected to the sense that, “Well, Ukraine will also get guarantees, that as these things are being delivered, they will be protected”?…. You know, it’s great to say you’re going to provide it, but does that imply any new sets of commitments? How much of this is the G7 also committing to not just the military side but to rehabilitating the Ukrainian economy? Because that’s going to be the critical test moving forward.

I understand, look, Ukraine needs all the help it can get. This is probably better than nothing. But the fact that it’s being discussed as a G7 initiative after a NATO summit is not, in my opinion, particularly reassuring. The United States has the ability to do certain things bilaterally, including…the president can designate Ukraine as a major non-NATO ally of the United States. [This] still has not occurred. The United States could pass bilateral security guarantees — it hasn’t. The Biden administration really wants to work through some sort of multilateral framework. I think, again, the administration is aware that doing things bilaterally with Ukraine may not be the image that they’re looking for. And so then we see this effort, well, this is a G7 effort, not a U.S. one.

RFE/RL: Also, we heard that France is open to discussing this, the U.K. is open to discussing it, the U.S. apparently is open to discussion…. If France, the U.S. and the U.K. are open to doing this, why is it not under the NATO umbrella? Because we are talking about three major states in NATO, right?

Gvosdev: Yes, these are three major states [in] NATO. They are three members of the United Nations Security Council. You would think that then they would have the heft. But the question is: Are these discussions to have discussions, while we give more time for the battlefield situation to resolve itself? The other question, again, is also what is going to be committed to?

Because if I’m a Ukrainian government official, I’m not going to trust statements, unless I know that they’re backed up by treaty agreement legislation. Just as a point of comparison, the United States, by law, is obligated to assist Taiwan in the event that China attacks. It’s not a matter of, “Well, do I feel like it would be nice?” It’s written into U.S. law. NATO obligations to NATO members are a matter of treaty. And so, if I’m a Ukrainian official, as much as I may welcome these discussions, I’m going to want to know what is it that you’re prepared to commit?

RFE/RL: Still, on the second part of the question, if this porcupine scenario ever were to occur, what would constitute the quills that the porcupine is defending itself with?

Gvosdev: This is where quantity matters. You need a quantity of equipment — so air defense missiles, anti-ship missiles, better electronic warfare — so that you can have a complete electronic fence, so to speak, so that any drone that crosses it is severed from communication by its controller. You want to have complete control [so] that no aircraft or cruise missile can transit your territory without a good chance of it being shot down. You want to — as the Ukrainians, by the way, have been doing already in the Black Sea — you want to be able to push naval power as far away from your shores as possible.

That’s all part of these quills…and it’s a quantity issue. You need to have such a quantity of the quills that you can essentially create this barrier — an electronic barrier, a military, artillery, missile barrier — that very few things can get through, and the things that do get through, you have a better chance of deflecting…. And this gets back to your earlier question. We should have seen this when people were saying this as of the summer of last year. We’re going to run into the supply issues. You need it, you want to be able to ramp up production. So, Ukraine still has this problem, and it has shortages. It has to essentially ration its artillery pieces that it’s using. And the Russians are able to take advantage of the gaps to continue to strike into Ukraine….

It doesn’t have to be high-tech; it doesn’t have to be the most expensive. It’s the idea that, when you look at a porcupine, each individual quill isn’t what stops you. It’s that they’re all together. If I put my hand on one quill, it might hurt, but I’m not going to put my hand on an entire collection of them. There’s lots of them. And that’s what creates deterrence. And what happens is that NATO needs to be able to construct, both for Ukraine, but along Ukraine’s periphery, so Romania, Poland, you want to have coverage over Ukrainian airspace and maritime space, where even from within a NATO country, you have essentially a line of launchers and equipment that can then cover Ukrainian territory.

That’s part of the security guarantees that also need to be discussed. And again, we’re 500 days into this war. I don’t have access to classified material. Maybe it’s happening quietly, but I’m just not seeing the industrial base moving along to, you know, we think of where we were in World War II by this point. The United States 500 days after Pearl Harbor, and you looked at what U.S. industry was able to [produce]. And I think because there’s this reluctance of saying, “Well, if we’ve started up and then the war is over, and we’ve lost all that money and product. So, let’s just keep running the stockpiles down.” And the decision on cluster munitions, that’s the canary in the coal mine. We’re sending these cluster munitions because we don’t have other things and [U.S. national-security adviser] Jake Sullivan [came out and said] very openly, “Well, this is the bridge, we need to send cluster munitions because we need to give industry time to build up the stockpiles.” And it’s 500 days. Why wasn’t this decision taken at day 100?

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

- Vazha Tavberidze is a staff writer with RFE/RL’s Georgian Service. As a journalist and political analyst, he has covered issues of international security, post-Soviet conflicts, and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations. His writing has been published in various Georgian and international media outlets, including The Times, The Spectator, The Daily Beast, and IWPR.