Philippines, China And US: Joint Exploration Vs Rearmament – Analysis

President Duterte’s joint exploration framework with China is a historical breakthrough. But since it has potential to de-escalate tensions over time, it is opposed by those interests that prefer rearmament, even if that would lead to a split of Southeast Asia and new nuclearization.

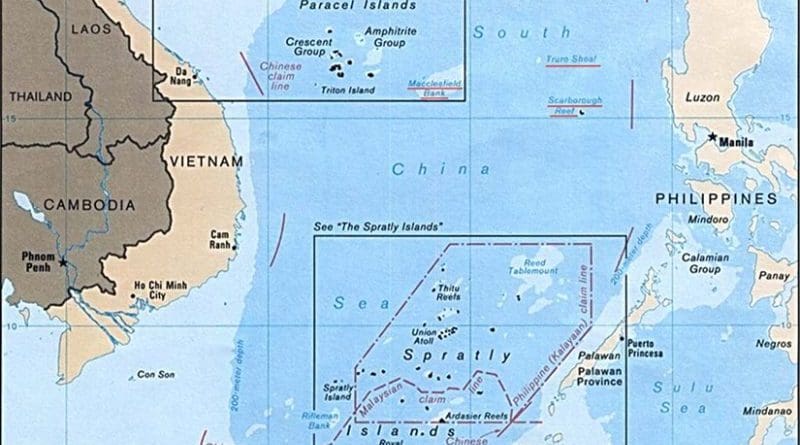

In early 2018, the Philippines and China agreed to set up a special panel to work out how the two could jointly explore oil and gas in parts of the South China Sea that both sides claim without having to address the issue of sovereignty. That was something of a breakthrough.

Last fall, President Xi Jinping’s state visit to the Philippines resulted in the bilateral memorandum of understanding on oil and gas development in the contested South China Sea (SCS). It was one of the some 30 documents signed during Xi’s visit in Manila.

Following a recent meeting with President Xi, Duterte said the Philippines could set aside the ruling of the international arbitral tribunal on China’s SCS claims, in exchange for a joint oil and gas exploration deal with Beijing.

The Xi-Duterte framework relative to Malampaya

To undermine the breakthrough and cooperation, critics argue that Duterte is “abandoning” the international ruling on South China Sea. In reality, setting aside the ruling does not mean abandoning it.

As I have argued since the early 2010s, the friction between the Philippines and China can be overcome by focusing on the economic cooperative potential, suspending the stated bilateral differences, creating mechanisms to settle those disagreements over time and fostering joint confidence-building measures. That’s what most ASEAN countries aspire to, including those that have SCS disagreements with China.

It may be useful to compare the stated joint exploration framework with another historical precedent. In 1989, during the rule of President Corazon Aquino, a gas field was discovered offshore Palawan. Following successful appraisal in the ‘90s – the reign of Fidel Ramos and Joseph Estrada, respectively – the Malampaya field became operational in 2001.

According to its operators’ estimate, as of 2018, the Malampaya, whose supply is forecast to start declining by 2022, has surpassed $10 billion in Philippine government revenues. That’s a nice way to say that that 90% of the Malampaya revenues go to multinationals in Europe and the US. In reality, the Philippine interest in the gas field is a just 10%, as opposed to the British-Dutch Shell (45%) and the US Chevron (45%).

According to President Duterte’s statement, China has promised to give the Philippines 60% of the profit from any gas or oil deal as opposed to China’s 40%. That’s a breakthrough; something that none of Duterte’s precursors achieved in the past decades.

Of course, there is another possible approach to the SCS issues, as well. After Duterte’s statement, Vice President Leni Robredo, the last major holdout of the Liberal Party meltdown following the 2016 election, blamed Duterte for a “shameful’ sellout to China over the joint-exploration deal. In turn, Duterte has argued that the Philippines needs to stop the “foolishness” of such scenarios.

Where would such scenarios lead?

The other scenario

In the April phone conversation between President Trump and President Duterte, Trump boasted about two US nuclear submarines near North Korea. “We have a lot of firepower over there,” Trump said. “We have two nuclear submarines — not that we want to use them at all.” The willingness to use nuclear weapons in the region is the latest phase in the ongoing rearmament.

During the Cold War, Washington created the security architecture in the region, including the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) signed in Manila, in the mid-50s. The SEATO’s stated task was to contain Soviet Communism. Hence, the U.S.-led wars from the Korean Peninsula in the early 1950s and the massacre of almost a million Communists and Chinese in Indonesia in the mid-‘60s to the war in Vietnam and subsequent conflicts in the former Indo-China in the ‘70s until the SEATO’s dissolution.

Today, the region looks very different. In relative terms, America’s economic role has been descending. Meanwhile, China has matured into a major economic contributor, as reflected by the economic spillovers associated with One Road One Belt initiatives.

Ever since President Obama’s pivot to Asia in the early 2010s, Pentagon has been pushing rearmament in the region, through arms sales. In 2017, the U.S. sold $42 billion in weapons to foreign countries, but $8 billion (20% of the total) in the “Indo-Pacific” region. Yet, in global arms transfers, Asia Pacific is the most lucrative region (over 40% of world total). Consequently, US defense contractors would like to double their revenues in the region.

Pentagon’s highest executives have a personal stake in rearmament. Former US Defense Secretary James Mattis served on the board of General Dynamics, a leading US defense contractor. His successor Patrick Shanahan served over 30 years in executive roles at Boeing, the largest US military exporter.

Current Defense Secretary Mark Esper has been recognized as America’s top military lobbyist. He spent seven years as the head of government relations at the leading defense contractor Raytheon.

In the early 2010s, the strategic goals of the former Aquino government and those of current Vice President Robredo have largely converged with the US “pivot to Asia.” As President Obama’s Defense Secretary Leon Panetta affirmed in 2012, this plan was predicated on the deployment of 60% of US warships to Asia Pacific by 2020 – that is, next year

Last month, Pentagon’s new chief Esper illuminated the next phase of US rearmament in the region.

Pentagon’s missile aspirations in Asia

A day after Washington withdrew from the landmark Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty with Russia – that President Reagan and Gorbachev in 1987 hoped would ensure peace in the 21st century – Esper stated the US will be looking to deploy new ground-launched, intermediate- range missiles in Asia.

According to Pentagon estimates, a low-flying cruise missile with a potential range of about 1,000km could be ready for deployment in 18 months. The US continues to have almost 4,000 nuclear warheads.

Esper has acknowledged the US is considering placing new medium-range conventional weapons in Asia: “We would like to deploy a capability sooner rather than later.” While he has not specified where the US intends to deploy these weapons, US allies in the region are historically prioritized.

In brief, geopolitical pressure toward missile deployments is about to begin in Southeast Asia.

ASEAN versus nightmare scenarios

In the Philippines, the history of nuclear deployments has been largely covert. Article II Section 8 of the Philippine Constitution forbids the presence of nuclear weapons in the country. But such clauses do not constrain its allies.

During the Cold War Marcos era, US nuclear warheads were secretly stockpiled in the Philippines. When the US Navy withdrew from Subic Bay naval base in 1992, it was due to the failure to iron out differences, including Manila’s ban on nuclear weapons.

By 1995, the ASEAN nations agreed on the Southeast Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty (SEANWFZ). The Bangkok Treaty entered into force on March 28, 1997 and obliges its members not to develop, manufacture or otherwise acquire, possess or have control over nuclear weapons. However, allies are not constrained by such limitations.

When President Aquino and Foreign Minister Rosario agreed with the US on a rotating US military presence at Philippine bases in March 2016 – right before Duterte’s landslide win – the effort seems to have been to lock in a path to closer military alignment (which eventually would require such deployments).

That scenario could bury the economic promise of the Philippines in the 21st century. President Duterte’s rebalancing, including a joint exploration deal, is an effort to foster new economic cooperation with China, in addition to the old ties with the US.

That rebalancing is very much in line with ASEAN’s efforts at peaceful, regional economic integration. Rearmament and nuclearization aren’t.

The original commentary was released by The Manila Times on September 15, 2019