Brazil Energy Profile: Third Largest Liquid Producer In Americas – Analysis

By EIA

Brazil is a significant energy producer. Increasing domestic oil production has been a long–term goal of the Brazilian government, and discoveries of large, offshore, pre–salt oil deposits have transformed Brazil into a top–10 liquid fuels producer.

Brazil is the ninth–largest liquid producer in the world and the third–largest producer in the Americas. In 2017, Brazil produced 3.36 million barrels per day (b/d) of petroleum and other liquids, making it the ninth–largest producer in the world and the third–largest in the Americas behind the United States and Canada.

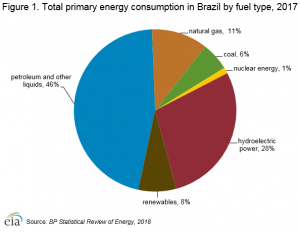

In 2017, Brazil was the eighth–largest energy consumer in the world and the third–largest energy consumer in the Americas, behind the United States and Canada. Total primary energy consumption in Brazil has grown by 28% in the past decade because of economic growth. Petroleum and other liquids represented about 46% of Brazil’s domestic energy consumption in 2017 (Figure 1).

Petroleum and other liquids

Sector organization

State–controlled Petrobras is the dominant participant in Brazil’s oil sector, holding important positions in upstream, midstream, and downstream activities. The company held a monopoly on oil–related activities in Brazil until 1997, when the government opened the sector to competition. Royal Dutch Shell was the first foreign crude oil producer in the country, and since then it has been joined by Chevron, Repsol, BP, Anadarko, El Paso, Galp Energia, Statoil, BG Group, Sinopec, ONGC, and TNK–BP, among others. Competition in the oil sector is not just from foreign companies. Brazilian oil company OGX, which is staffed largely with former Petrobras employees, started to produce oil in the Campos Basin in 2011.

Petrobras’s wholly–owned subsidiary, Transpetro, services Petrobras’ oil and natural gas production, logistics, and refining and distribution areas by carrying and storing oil, natural gas, derivatives, and biofuels. Transpetro carries imported and exported cargo of oil and other products. As with the refining sector, Petrobras holds most of Brazil’s logistics infrastructure. Its main clients, in addition to the Petrobras System, are distribution and petrochemical companies.

Petrobras is currently under investigation in Brazil and in the United States for bribery and money laundering. The investigation into the multi–billion dollar corruption scandal (Operation Car Wash) started in March 2014 with the arrest of Paulo Roberto Costa, head of refining operations for Petrobras (2004–2012), who was accused of money laundering. The scope of the scandal escalated further with allegations of government corruption and a kickback scheme, resulting in losses by Petrobras of more than $8 billion, multiple arrests, and the resignation of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Maria das Graças Foster. More than 80 people have been charged with bribery and money laundering, including some of Brazil’s most prominent politicians and business owners.

In August 2016, President Dilma Rousseff was impeached and removed from office by Brazil’s Senate because her 2014 presidential campaign received illegal donations through Operation Car Wash. [1] Former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has also been accused of involvement in the corruption scheme. He was sentenced in 2017 because of illegal benefits received in return for contracts with state–run oil company Petrobras. Lula da Silva is expected to face other sentences in the coming months because he is a defendant in nine different cases. [2] Michel Temer of the centrist Democratic Movement Party, PMDB, was named interim president until the 2018 elections. In May 2017, President Temer was formally accused of conspiring to obstruct the investigation, setting the stage for a constitutional battle between the judiciary and the executive branch of the government and prompting calls in Congress for his impeachment. President Temer has denied the charges. Petrobras’ CEO Aldemir Bendine (2015–2016) was arrested and convicted of corruption charges and sentenced to 11 years in prison in March 2018. [3]

In May 2018, Brazilian truckers went on strike for 10 days, erecting roadblocks to seal off highways across the country as a protest against rising fuel prices set under Petrobras’ direction. In June 2018, Petrobras’ CEO Pedro Parente, resigned because of the government’s agreement to subsidize the cost of diesel in order to drop the price at the pump by 12% and end the strike. Parente, as Pebrobras’ CEO, was opposed to this policy having sought to align fuel prices more closely with international markets through nearly daily price adjustments during his term as CEO. [4]

In 2017, Petrobras reduced its debt to $85 billion, the lowest figure since 2012. [5] Petrobras’ strategy to reduce its debt relies on a strong restructuring plan through an ambitious divestment program. Currently, Petrobras’ plan includes divesting its stake in 105 mostly onshore oil fields.

The principal government agency charged with regulating and monitoring the oil sector is the Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis (ANP). ANP is responsible for issuing exploration and production licenses and ensuring compliance with relevant regulations.

In February 2017, the Brazilian Energy Ministry proposed changes to rules regarding minimum percentages of the locally–sourced goods and services required in exploration and production contracts (known as local content), reducing requirements by approximately half. Brazil’s previous local content rules were seen as a disincentive for investment as a result of the limited and uncompetitive local supply chain. [6] Previously, oil and natural gas operators in Brazil were required to use up to 85% of equipment and services from domestic industry. This percentage was one of the highest local content requirements in the world, contributing to high breakeven prices.

The local content rules were revised in early 2018 and affect contracts for older bid rounds, including the first–ever production–sharing agreements, and projects through 2030. These changes could significantly affect Brazil’s rate of oil production growth in the future, and breakeven prices could fall significantly. The new local content rules set the overall requirement at 50% for onshore projects, and 18% for offshore deepwater projects. The government also instituted less stringent fines for companies that are unable to fulfill these local content requirements. However, companies will no longer be able to apply for a waiver of these fines. [7]

Production and consumption

More than 94% of Brazil’s oil reserves are located offshore, and 80% of all reserves are found offshore near the state of Rio de Janeiro. The next largest accumulation of reserves is located off the coast of Espírito Santo state, which contains about 10% of the country’s oil reserves. Reserves are expected to rise as pre–salt resources are further explored.

In July 2017, output from pre–salt offshore wells surpassed combined volumes from all other fields for the first time. [8] In 2018, Petrobras brought online four floating production, storage, and offloading vessels (FPSO) each with a production capacity of 150,000 b/d. Petrobras expects to add up to eight more FPSOs in 2019, with more planned through 2024 as Petrobras brings on new units at the Libra, Lula, Tartaruga Verde, Buzios, and Tartaruga Mestiça offshore fields. [9]

Petrobras and its partners (Royal Dutch Shell Plc, France’s Total SA, China’s CNOOC and National Petroleum Corp) will install the first of four commercial production systems in the Libra offshore field through 2023. This lease is Brazil’s first ever under a production–sharing system with the government. [10]

Refining

Unless major refining capacity is added in Brazil, oil product demand is expected to continue to outpace the country’s domestic refining capacity. Petrobras operates 12 of Brazil’s 17 refineries, which together account for 98% of the country’s crude oil distillation capacity (Table 2). [11] Most of the refineries are located near demand centers on the country’s coast.

| Refinery | Operator | Capacity (thousand b/d) | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paulínia (REPLAN) | Petrobras | 415 | Paulínia, São Paulo |

| Mataripe (RLAM) | Petrobras | 315 | Mataripe, Bahia |

| São Jose dos Campos (REVAP) | Petrobras | 252 | São Paulo, São Jose dos Campos |

| Duque de Caxias (REDUC) | Petrobras | 239 | Rio de Janeiro state |

| Araucária (REPAR) | Petrobras | 208 | Araucária, Paraná |

| Canoas (REFAP) | Petrobras | 201 | Canoas in the Rio Grande do Sul state |

| Cubatão (RPBC) | Petrobras | 170 | Cubatão, São Paulo |

| Betim (REGAP) | Petrobras | 157 | Betim, Minas Gerais |

| Abreu e Lima (RNEST) | Petrobras | 74 | Ipojuca, Pernambuco |

| Capuava (RECAP) | Petrobras | 53 | Capuava, Maua, Sao Paulo |

| Manaus (REMAN) | Petrobras | 46 | Manaus, Amazonas |

| Fortaleza (LUBNOR) | Petrobras | 8 | Fortaleza, Ceara |

| Total | 2,138 | ||

| Sources: Oil & Gas Journal, 2018 Worldwide Refining Survey |

In November 2014, the Abreu e Lima, or “RNEST” refinery began processing crude oil, marking the first greenfield refinery addition in Brazil in more than a decade; the second 115,000 b/d phase is expected to be completed by 2020. [12]

In early 2015, Petrobras officially canceled the 600,000 b/d Premium I and 300,000 b/d Premium II refineries because of the company’s critical financial situation. [13] In 2017, Petrobras approved the re–evaluation of the Petrochemical Complex of Rio de Janeiro Comperj project, located in the city of Itaboraí, Rio de Janeiro, in 2017. In July 2018, Petrobras announced a partnership with China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), focused on the completion of Comperj’s Refinery and a participation in the Marlim cluster of fields (Marlim, Marlim Sul and Marlim Leste) in the Campos Basin in Brazil. [14]

Exports and imports

Because Brazil’s refineries do not have the technical capabilities to process heavier crude oils, the country must export some of its heavy crude oil and import lighter crude oil.

In addition, Brazil continues to be an importer of petroleum products to meet the rising domestic demand, compensate for its fuel price subsidies, and supplement its underinvestment in the refining sector.

Pre–salt oil

Pre–salt oil is generally characterized as oil reserves situated exceptionally deep, below the ocean, under thick layers of rock and salt that require substantial investment to extract. The large depth and pressure involved in pre–salt production present significant technical hurdles that must be overcome.

In 2005, Petrobras drilled exploratory wells near the Tupi field and discovered hydrocarbons below the salt layer. In 2007, a consortium of Petrobras, BG Group, and Petrogal drilled in the Tupi field and discovered an estimated 5 billion–8 billion barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) resources in a pre–salt zone 18,000 feet below the ocean surface, under a thick layer of salt. For comparison, EIA defines ultradeep drilling in the Gulf of Mexico as 5,000 feet or more. Further exploration showed that hydrocarbon deposits in the pre–salt layer extended through the Santos, Campos, and Espírito Santo Basins. Following Tupi, many pre–salt finds were announced in the Santos Basin. Pilot projects in the Lula and Sapinhoá fields in the Santos Basin began production in 2009 and 2010, respectively. With the exception of the Libra field, all pre–salt areas currently under development were non–competitively granted to Petrobras.

Regulatory reforms

Before the pre–salt discoveries, Brazilian law allowed all companies to compete in auctions to win concessions and to operate exploration blocks. This law changed in 2010, when the Brazilian government passed legislation instituting a new regulatory framework for the pre–salt reserves. Included in the legislation were four notable components. First, the legislation created a new agency, Pré–Sal Petróleo SA, to administer new pre–salt production and trading contracts in the oil and natural gas industry. The second component allowed the government to capitalize Petrobras by granting the company 5 billion barrels of unlicensed pre–salt oil reserves in exchange for a larger ownership share. The other two components established a new development fund to manage government revenues from pre–salt oil and to lay out a new production–sharing agreement (PSA) system for pre–salt reserves. In contrast to the concession–based framework for non–pre–salt oil projects, where companies are largely uninhibited by the state in exploring and producing, Petrobras will be the sole operator of each PSA and will hold a minimum 30% stake in all pre–salt projects. However, to incentivize companies, the PSA will also include a signing bonus of $6.6 billion and a low–cost recovery cap.

In 2016, Brazil’s government passed an offshore oil bill that allows greater private and foreign investment in the development of Brazil’s offshore oil blocks. With the modification, Petrobras changed from mandatory operator to preferred operator, allowing the company to choose which biddings for blocks in the pre–salt areas it wanted to participate in. [15]

Biofuels

To address the country’s dependence on oil imports and its surplus of sugarcane, the government implemented policies to encourage ethanol production and consumption beginning in the 1970s.

In Brazil, ethanol and gasoline are competing products in a market where flex–fuel vehicles account for 60% of the total domestic vehicle fleet. Hydrous ethanol (E100) is the substitute product that flex–fuel vehicle owners switch to when its price is at or lower than 70% of the gasoline price. In 2015, Brazilian motorists consumed more ethanol than gasoline despite falling oil prices, ending several years of rising gasoline sales that were largely subsidized by Petrobras.

The Brazilian government raised the ethanol blend requirement in gasoline to 27% in February 2015. The government is considering an increase to 27.5% as a measure to reduce gasoline imports. [16] However, the ethanol industry is struggling because of land and labor cost increases as well as government–imposed gasoline price controls, which are undermining the competitiveness of ethanol as an oil substitute. In addition, sugarcane, which is the feedstock in Brazil’s ethanol production, is highly sensitive to weather. Crop yields can swing considerably year to year, adding significant uncertainty and costs.

Brazil also produces biodiesel. More than 43% of biodiesel production is concentrated in Brazil’s central west region of the country. In March 2018, Brazil increased the biodiesel–use mandate from 8% (B8) to 10% (B10), one year ahead of schedule. [17]

Imports and tariffs

Historically, droughts in Brazil have forced the country to import ethanol. In addition, if sugarcane is not quickly processed into ethanol, the crop is prone to rot. The seasonality of sugarcane harvests leaves Brazil with an off–season from January to March. In Brazil, ethanol production is also highly sensitive to commodity prices. For example, because sugarcane is used for ethanol production, high sugar prices may entice producers to switch to sugar production instead of ethanol production. Finally, demand in northeast Brazil for imported ethanol has been strong as a result of insufficient local production and the higher cost of transporting ethanol from southern Brazil. [18]

In August 2017, Brazil’s foreign trade chamber Câmara de Comércio Exterior (CAMEX) approved a 20% tax on ethanol imports to take effect once a 600 million liter–per–year quota (10,339 b/d) is exceeded. In the first half of 2017, Brazilian ethanol imports reached 1.29 billion liters, a 330% increase compared to the same period a year earlier. [19] The import tax ends an agreement between the two largest ethanol producers in the world, Brazil and the United States, to keep global ethanol trade free of taxes as a way to boost the industry and the market. CAMEX stated that the tax will be in place for two years, and after that the tax would be reevaluated.

Natural gas

Sector organization

Petrobras plays a dominant role in all links of the natural gas supply chain. In addition to controlling most of the country’s natural gas reserves and being responsible for most domestic Brazilian natural gas production, it also manages natural gas imports from Bolivia. Petrobras controls the national transmission network, and it has a stake in 21 of Brazil’s 27 state–owned natural gas distribution companies. Petrobras owns and operates virtually all of Brazil’s pipeline infrastructure through its subsidiary company Transpetro. In the upstream and the midstream sector, Brazil’s Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) sets policy, and the ANP is the regulatory authority. In the downstream sector, state agencies oversee regulation.

In April 2017, Petrobras sold a 90% stake in its natural gas pipeline unit, Nova Transportadora do Sudeste SA, to a consortium of foreign investors. Petrobras is also planning to sell its natural gas pipeline network company Transportadora Associada de Gás S.A. (TAG). [20] Petrobras plans to continue divestment by selling its liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) distribution unit, Liquigas. [21]

In mid–2016, MME launched the initiative Gas to Grow. This initiative “aims at improving the regulatory framework of the sector, laying the groundwork for a competitive market by adopting best international practices” to “build a favorable environment for new investments.” [22]

In April 2017, Energy Minister Filho announced that Brazil would reach self–sufficiency in natural gas supply within five years, benefiting from ultra–deepwater hydrocarbon production. Brazil currently relies on Bolivia to meet its natural gas needs, importing under a supply agreement that expires in 2019. [23] In particular, Petrobras expects strong production from pre–salt resources in the Pão de Açúcar in the Campos Basin and Carcará fields starting in the early 2020s.

Reserves

Most of Brazil’s natural gas reserves (84%) are located offshore, and 73% of offshore reserves are concentrated off the coast of the state of Rio de Janeiro. Of the country’s onshore natural gas reserves, 59% of the reserves are located in the state of Amazonas. [24]

Production and consumption

Over the last years, natural gas production in Brazil has been driven by three basins: Santos, Campos and Espirito Santo.

Recent announcements about additional natural gas discoveries in Brazil’s offshore pre–salt layer have generated excitement about new natural gas production. Along with the potential to significantly increase oil production in the country, the pre–salt areas are estimated to contain sizable natural gas reserves as well. [25] Associated natural gas projects in the massive pre–salt oil fields (Campos and Santos Basins) will account for the bulk of production growth going forward. However, as a result of the lack of offtake infrastructure from the offshore fields to themainland, challenges remain because significant volumes are currently re–injected or flared.

Pipelines

The Brazil pipeline system is a networks of pipes situated predominantly along the southeast and northeast areas of the country, from the state of Rio Grande to Sul to Ceará. For years, these pipelines were not interconnected, which hindered the development of domestic production and consumption. However, in March 2010, the Southeast Northeast Integration Gas Pipeline (GASENE) linked these two markets for the first time. This 860–mile pipeline, which runs from Rio de Janeiro to Bahía, is the longest pipeline in Brazil.

The other major natural gas market in Brazil is in the Amazon region. In 2009, Petrobras completed construction of the Urucu pipeline linking Urucu to Manaus, the capital of Amazonas state. This project is expected to facilitate development of the Amazon’s considerable natural gas reserves.

In May 2016, Petrobras brought online its OCVAP 1 pipeline from its Caraguatatuba natural gas treatment unit to the Revap refinery in Sao Paulo State, transporting pre–salt natural gas from Brazils’s southeast coast. [26] A third pipeline operated by Petrobras that transports pre–salt natural gas is expected to come online in 2020. [27]

Imports

Brazil imports natural gas from Bolivia through two pipelines (Table 3). Flows from Bolivia to Brazil have remained at about capacity over the past 10 years.

| Pipeline | Length | Origin | Destination | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gasbol | 1,960 miles | Santa Cruz, Bolivia [28] | Corumbá, Brazil, contining to São Paulo, Brazil | 1.1 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) |

| Río San Miguel –San Matías | 391 miles | San José de Chiquitos, Bolivia | San Matías, Brazil; connecting to the GasOcidente pipeline | 98 MMcf/d |

| Sources: Ministry of Mines and Energy [29] and GasOriente Boliviano [30] |

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) demand grew significantly in Brazil between 2012 and 2015 as a result of increased natural gas use for electric power generation. During those years, low rainfall levels limited the availability of hydroelectric power. Robust economic growth also contributed to industrial demand growth, as well as overall power demand growth. However, the return of normal rainfall levels at the end of 2015, as well as the second consecutive year of economic recession, reversed these trends sharply in 2016, cutting deeply into natural gas demand. With gradually increasing production and limited demand growth, LNG imports are likely to remain relatively low. However, LNG imports are expected to rise again beginning in the early 2020s when the country’s first long–term sale and purchase agreement (SPA) to supply the Centrais Elétricas de Sergipe S.A (CELSE) LNG–to–wire project starts.

Brazil has three LNG regasification terminals with a combined capacity of 1.4 Bcf/d: the Pecém terminal in the northeast, the Guanabara Bay terminal in the southeast, and the TRB terminal in the state of Bahía. [31] The facilities are floating regasification and storage units (FRSU).

Electricity

Brazil has the third–largest electricity sector in the Americas behind the United States and Canada.

Because most of Brazil’s generation capacity is located far from urban demand centers, significant investment in transmission and distribution systems is required. The Madeira transmission line, completed in 2014, is the longest high–voltage, direct–current line in the world and spans 1,476 miles to link hydropower plants in the Amazon Basin to major load centers in the southeast. Increased emphasis on distributed generation will help reduce the need for additional transmission infrastructure in the future.

Sector organization

The government plays a substantial role in the Brazilian electricity sector. Until the 1990s, the government almost completely controlled the electricity sector. Brazil initiated an electricity sector privatization process in 1996 that led to the establishment of Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica (ANEEL). Although the electricity sector was privatized in the early 2000s, the bulk of Brazil’s major generation assets remain under government control. Eletrobrás, a state–owned holding company, is the dominant player in the electricity market. The government also owns almost the entire electricity transmission network.

In 2004, the Brazilian government implemented a new model for the electricity sector. This hybrid approach to government involvement splits the sector into regulated and unregulated markets for different producers and consumers. This approach allows for both public and private investment in new generation and distribution projects. Under the plan, Eletrobrás was formally excluded from privatization efforts. In August 2017, the Brazilian government announced its intention to divest its controlling stake in Eletrobrás. [32] The sale will not include Eletronuclear (a nuclear power company owned by Eletrobrás) or the Itaipu hydroelectric dam.

Hydroelectric power

Many of Brazil’s hydropower generating facilities are located far from the main demand centers, which results in high transmission and distribution losses. Brazil currently depends on hydropower to provide more than two–thirds of its electricity, and natural gas– and diesel–fired plants are used only to meet peak demand or as backup baseload sources. [33]

Increased droughts in Brazil have led to concerns about hydroelectric power generation. Water reservoirs have experienced decreased water levels since 2013, made worse by the 2015–2016 El Niño event in the southeast region that caused the worst water shortage seen in 35 years. [34] As hydroelectric output fell during this period, generation from other fuels such as natural gas and liquid fuels increased. With the arrival of the 2016 rainy season, the drought in Brazil eased, except in the Northeast where reservoirs remained at historically low levels.

The world’s largest hydroelectric plant by installed generation capacity is the 14 GW Itaipu hydroelectric dam on the Paraná River, which Brazil operates with Paraguay. According to Itaipu Binacional, the facility generated a record 103 million megawatt hours (MWh) of electricity in 2016, benefitting from higher rainfall and improved operating efficiency. [35] Although Brazil is weighing plans to reduce hydropower in the generation mix to minimize the risk of supply shortages as a result of dry weather, new hydro projects continue to move forward. Most notable among these projects is the Belo Monte plant in the Amazon Basin, which upon reaching full operating capacity in 2019, will have the third–largest hydroelectric plant capacity in the world behind China’s Three Gorges Dam and the Itaipu Dam.

Nuclear power

Brazil has two nuclear power plants, the 640 megawatt (MW) ANGRA 1 and the 1,350 MW ANGRA 2. State–owned Eletronuclear, a subsidiary of Eletrobrás, operates both plants. The ANGRA 1 nuclear power plant began commercial operations in December 1984, and the ANGRA 2 began commercial operations in December 2000. Construction of a third plant, the 1,405 MW Admiral Alvaro Alberto Nuclear Power Station (CNAA), formerly ANGRA 3, started in 1984 but came to a halt in 2015 after Eletronuclear officials were arrested as part of a corruption investigation. [36]

Solar

Brazil has 320 MW of distributed solar generation, which increased 304% between 2016 and 2017. [37]

In June 2017, Enel Green Power Brasil announced the start of commercial operations at the Lapa complex in the northeastern state of Bahia. The solar park operates installed capacity of 158 MW, comprising the Bom Jesus da Lapa (80 MW) and Lapa (78 MW) plants. [38] In September 2017, Enel Green Power Brasil commenced operations at its Ituverava (254 MW) and Nova Olinda (292 MW) solar parks. Ituverava is located in the municipality of Tabocas do Brejo Velho in the north eastern state of Bahia, and Nova Olinda is located in the municipality of Ribeira do Piauí, in the north eastern state of Piauí. These projects combined capacity is 546 MW, and they are South America’s largest PV facilities in operation. [39]

Notes:

- In response to stakeholder feedback, the U.S. Energy Information Administration has revised the format of the Country Analysis Briefs. As of January 2019, updated briefs are available in two complementary formats: the Country Analysis Executive Summary provides an overview of recent developments in a country’s energy sector and the Background Reference provides historical context. Archived versions will remain available in the original format.

- Data presented in the text are the most recent available as of April 2019.

- Data are EIA estimates unless otherwise noted.

Endnotes:

- New York Times, “Dilma Rousseff Is Ousted as Brazil’s President in Impeachment Vote,” August 31, 2016.

- BNAmericas, “Lula begins serving 12–year sentence for corruption,” April 7, 2018.

- Reuters, “Ex–Petrobras CEO Bendine convicted of corruption in Brazil,” March 7, 2018.

- New York Times, “Truckers’ Strike Paralyzes Brazil as President Courts Investors,” May 28, 2018.

- Petrobras, “Petrobras posts profit in the first half and reduces its debt,” August 3, 2018.

- BNAmericas, “Brazil to ease local content rules for existing E&P contracts,” July 18, 2017.

- BNAmericas, “Brazil eases E&P local content rules,” April 12, 2018.

- Upstream, “Pre–salt leads Brazil oil production,” July 31, 2017.

- Petrobras, “Business and Management Plan, 2019–2023.”

- Rigzone, “Petrobras Sets 2020 for Start of First Libra Oil Production System,” October 23, 2016.

- Petrobras, “Annual Report 2017” (page 82).

- Petrobras, “Annual Report 2017” (page 82).

- BNAmericas, Premium I Refinery profile.

- Petrobras, “Petrobras and CNPCI sign Heads of Agreement to promote investments in Comperj Refinery and Marlim Cluster,” July 4, 2018.

- Financial Times, “Brazil to ease Petrobras pressure with offshore oil bill“

- Biofuels Digest, “Biofuels Mandates Around the World: 2016,” January 3, 2016.

- Biodiesel Magazine, “Brazil implements B10 mandate a year ahead of schedule,” March 5, 2018.

- US Department of Commerce, “2016 Top Markets Report Renewable Fuels Country Case Study: Brazil”

- Reuters, “Brazil approves quota, 20 percent tax on ethanol imports,” August 23, 2017.

- Petrobras, “Sale of 90% equity interest in TAG: Opportunity Disclosure – Teasers,” September 5, 2017.

- Reuters, “Brazil’s Petrobras to consider LPG unit sale, IPO,” March 12, 2018.

- Petrobras, “Report of the Administration 2016“.

- BN Americas, “Brazil nearing natural gas self–sufficiency, says minister,” (April 11, 2017).

- Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis, “Oil, Natural Gas, and Biofuels Statistical Yearbook 2017” (2017).

- Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis, “Oil, Natural Gas, and Biofuels Statistical Yearbook 2017” (2017).

- BN Americas, “Petrobras opens pre–salt natural gas pipeline – Bnamericas,” (May 16, 2016).

- Rystad,” Pre–Salt Rich Brazil – Gas Imports? Yes Please,” July 11, 2018.

- GasOriente Boliviano, “GasOriente Boliviano” (Accessed September 17, 2018).

- Ministry of Mines and Energy, “Boletim Mensal de Acompanhamento da Indústria de Gás Natural,” October 2014.

- GasOriente Boliviano, “GasOriente Boliviano” (Accessed September 17, 2018).

- Ministry of Mines and Energy, “Boletim Mensal de Acompanhamento da Indústria de Gás Natural,” October 2014.

- BN Americas, “Brazil close to unveiling Eletrobrás privatization model,” (September 12, 2017).

- BN Americas, “Brazil nearing natural gas self–sufficiency, says minister,” (April 11, 2017).

- US Energy Information Administration, “Hydroelectric plants account for more than 70% of Brazil’s electric generation” (August 22, 2016).

- Itaipu Binacional, “Production from Year to Year,” (Accessed September 17, 2018).

- Reuters, “Eletronuclear head says may not honor Angra three debts: paper,” July 16, 2018.

- CleanTechnica,”Brazil To Hit 2 Gigawatts Of Installed Solar By End Of 2018,” May 15, 2018.

- BN Americas, “Enel Brings Online Brazil’s Largest Solar Park,” (June 5, 2017).

- ENEL Green Power press release, September 18, 2017.