Export Of Monkeys To China Is A Violation Of Shared Cultural Values – Analysis

The mythical monkey Sun Wukong is exalted in Chinese mythology as Hanuman is in Indic mythology.

Religious and cultural objections have been raised in Sri Lanka in the ongoing controversy over a proposal to export 100,000 toque macaque monkeys to China.

Experts in Sino-Indian mythology point out that, like Hanuman in India, the “monkey king” Sun Wukong has an exalted place in Chinese mythology.As such, the export of 100,000 toque macaque monkeys to China can be seen as a violation of shared cultural values.

The Sri Lankan Tamil Hindus associate the monkey with the deity Hanuman, a key character in the epic Ramayana. The Sinhala-Buddhists also believe in the sacredness of Hindu deities, including Hanuman. The latter have erected a temple for him at Rumassala in a Buddhist-majority area in South Sri Lanka.

A Sinhala-Buddhist, Dr.Raveendra Kariyawasam, National Coordinator of the Center for Environmental and Nature Studies Colombo, has written to the Indian High Commissioner Gopal Baglay asking for India’s intervention to stop the sale of the endangered toque Macaques to China because it is tantamount to showing disrespect to the cultural sensitivities of the Tamils of Sri Lanka. He further said that the Ramayana is part of the cultural landscape of both India and Sri Lanka and described China’s interference in such cultural matters as “atrocious.”

There is widespread doubt if the 100,000 monkeys will be sent to zoos, as claimed. There is speculation about their ending up in scientific labs as guinea pigs or on dining tables as a prized delicacy.

A former Minister of Wildlife, Navin Dissnayake, has said that in all likelihood, the 100,000 monkeys will not be sent to zoos (there are only 18 zoos in China) but to labs for research. There, these monkeys will be subjected to torture, Dissanayake said.

“The proposal to send them to China is an abomination. These beautiful creatures have every right to live in their natural habitat in Sri Lanka.”

Chinese Mythology

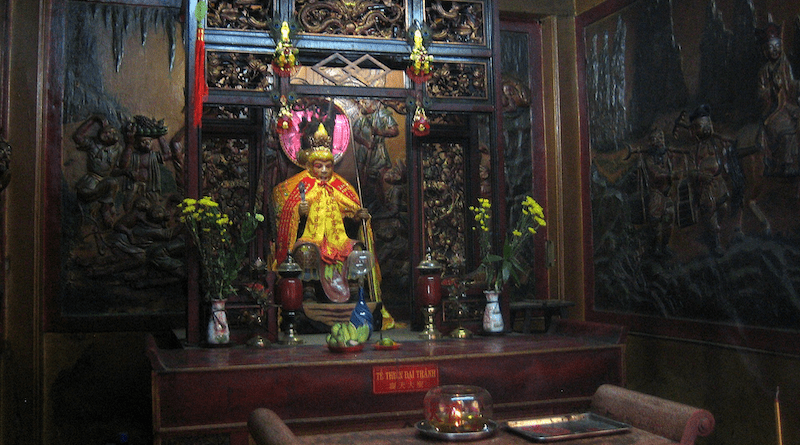

Interestingly, the monkey enjoys a respectable place in Chinese culture too. Scholars say that the Chinese began venerating the mythical monkey Sun Wulong (known as Monkey King) because he had provided security to Xuan Zang ( Hiuen Tsang) during his perilous travels in India to collect Buddhist Sutras in the 7 th. Century.

Sun Wulong is a central character in the novel Journey to the West on Xuan Zang’s travels written by Wu Cheng’en during the rule of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

In Chinese mythology, just like Hanuman, Sun Wulong is known for his boldness, loyalty, quick wit, and above all, enormous strength. In addition, he is portrayed as being artistic (a Chinese addition). Like Hanuman, Sun Wulong is very popular.

In Hindu mythology, Hanuman is immortal. So is Sun Wulong. Both can overcome adversaries or adverse circumstances through innovative ways. Like Hanuman, Sun Wukong can shapeshift at will, according to the website formfluent.com. Again like Hanuman, Sun Wukong can lift mountains (except Mount Tai). Both Hanuman and Sun Wukong had gained immortality.

In 2003, in a bid to revive Chinese traditional culture, China Central Television Channel 4, ran a 10-part serial on Sun Wukong.

Inspired by Hanuman?

Was the myth of Sun Wukong inspired by Ramayana’s Hanuman? They are uncannily similar but while Hanuman is worshiped in India Sun Wukong is only admired, not worshiped, in China.

In a 2020 article in Sunday Guardian Prof.B.R.Deepak of the Center of Chinese and Southeast Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, traced the link between Hanuman and Sun Wukong.

He quotes Chinese writer Lu Xun (1881-1936) to say that during the Wei (AD 386-534) and Jin (AD 266-420) dynasties, translations of Buddhist sutras and Indian fables spread in China.

After 7th century AD, Buddhism gradually declined in India and was almost extinct in the 13th century. Therefore, what was disseminated in Southeast Asia was largely a mix of Buddhism and Hinduism. The existence of Buddhist and Indian temples in Quanzhou bear testimony to the syncretic Hindu-Buddhist influence in China.

According to Liu Anwu, during the Tang, Song and Yuan dynasties, Guangzhou, Quanzhou, Mingzhou, Yangzhou were the world’s busiest international business hubs that were frequented by merchants, sailors, and monks from India.

“The story of Rama must have been the subject of their pastime; therefore, it was natural for the story, including that of Hanuman, to spread in the southeast coast of China,” Prof. Deepak says.

The Chinese literati loved mysteries hidden in these tales and used them consciously or unconsciously in their writings. And despite Sinicization, Vimalakirti, Avalokitesvara, Maudgalyayana and Hanuman are today part of Chinese mythology, he adds.

The portrayal of Sun Wukong began in the Song and Yuan dynasties. But it was not until the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) that this supernatural character was transformed into a colorful figure in the form of Sun Wukong.

Three Schools of Thought

Among Chinese scholars, there are three schools of thought on Sun Wukong, says Prof. Deepak. Cai Tieying, author of Epiphany and Immortality: A Biography of Cheng’en had stated these three theories.

The first is the “Local product theory” of Lu Xun (1881-1936), which refutes the belief that the Ramayana had influenced the creation of Sun Wukong. According to Lu Xun, the Chinese monkey king developed from a water goblin.

The second is the “Foreign import theory”, which Hu Shi had proposed in the 1920s. This draws parallels between the Journey to the West and the Ramayana and sees similarities in the characterization of Sun Wukong and Hanuman. Hu Shi propounded his theory after a deep study of the Journey to the West. Dr. Baron Alexander von Stael Holstein, a leading Indologist and Buddhist scholar, had also said that Sun Wukong was crafted in the image of Hanuman of the Ramayana.

The third is the “Hybrid theory” which argues that the image of Sun Wukong is a mix of local and foreign (Indian) traditions. According to Ji Xianlin, the most famous representative of the “Hybrid School”, while one cannot refute the relationship between Sun Wukong and Hanuman of the Ramayana, it cannot be denied that the Chinese had “developed” Sun Wukong innovatively. The Chinese Sun Wukong was at once strong and artistic. The Chinese people loved this mix.

The latest masterpiece supporting the hybrid theory is Liu Anwu’s book Comparative Studies of Indian and Chinese Literature, Deepak says.

A scholar in Sanskrit and Hindi besides Chinese, Liu Anwu (1930-2018) dedicated two chapters titled “Rescuing the kidnapped wife: Rama’s story in the Journey to the West”, and “A Comparison of the Curse Mantra and other Mantras: Hindu Mythology and Journey to the West” to prove his point by referring to a mass of original sources.

Liu Anwu established that various descriptions of Sun Wukong in the Journey to the West are very consistent with or similar to the Rama story in the Buddhist sutras and the great epic Ramayana itself.

“When you look at these descriptions independently and individually, you don’t necessarily think that they are borrowed from somewhere, but believe that they are created in parallel. But seeing holistically, you will have the second thought about them,” Liu Anwu wrote.

Sun Wukong is but the crystallization of the integration of Chinese and Indian literary images in the long process of cultural exchanges between India and China. It is a Sino-Indian hybrid.